What is Purim?

Purim (which means “lots” in Persian) is the Jewish holiday that celebrates how the Jewish people were saved from annihilation in ancient Persia as told in the Biblical book of Esther.

In the story, Haman, the evil advisor to King Ahasuerus of Persia, plots to kill all the Jews. However, through the courageous actions of Queen Esther and her cousin Mordechai, Haman’s evil plan is derailed and the Jewish people are spared.

Purim is called the “Festival of Lots” because Haman casts lots to determine when he would carry out his plan (in Esther 3:7). (For a different explanation of the meaning of the name “Purim,” that it was really named after Esther’s actions, we recommend this video from our friends at Aleph Beta.)

On Purim, Jews celebrate the great reversal of fortune of the Jews of Persia and how the day that was originally set for their destruction transformed into one of great joy and celebration.

Purim is one of the most festive and joyous occasions of the year, but it also grapples with the deeper and more troubling themes of the story.

Read more: Get our guides to all the Jewish holidays.

When is Purim 2024?

Purim starts the evening of Saturday, March 23, 2024, and ends the evening of Sunday, March 24, 2024.

How is Purim celebrated?

Purim is an extremely festive and joyous occasion that is celebrated with the community. The Babylonian sage Rava famously said (in Megillah 7b): “A person is obligated to become intoxicated (“livasumei”) on Purim until he does not know the difference between ‘cursed is Haman’ and ‘blessed is Mordechai.’”

(Some authorities amended this, saying that it is not necessary to become drunk, but one may drink more than usual. Additionally, this certainly does not apply to those below the drinking age, and everyone ought to drink responsibly on Purim.)

A few of the ways Purim is typically celebrated include:

- Reading the Megillah or “scroll” (i.e., the Book of Esther) at night and in the morning

- Making noise with groggers (noisemakers) whenever Haman’s name is mentioned in the Megillah reading

- Dressing up in costumes

- Having a festive holiday meal

- Drinking and merrymaking

- Eating 3-cornered filled pastries called hamantaschen

- Putting on a humorous play in costumes known as a Purim shpiel (this means “play” in Yiddish)

- Giving gifts of pastries and other food (mishloach manot) to friends and neighbors

- Giving gifts of money, food or drinks to the poor (matanot l’evyonim)

When is Purim?

Purim occurs on the 14th of the Hebrew month of Adar (during leap years, which happen every two to three years in the Hebrew calendar, an extra month, Adar II, is added and it is celebrated on the 14th of Adar II).

This year, Purim begins the evening of Monday, March 6 and ends the evening of Tuesday, March 7. However, in Jerusalem and other walled cities, it is celebrated on the 15th of Adar, based on verses from Chapter 9 from the Book of Esther.

The day before Purim (the 13th of Adar) is a fast day called Ta’anit Esther (the Fast of Esther). The fast commemorates how Esther and the entire Jewish community of Shushan fasted for three days before Esther approached the king (in Esther 4:16). Read more in the story of Purim below.

How to greet someone on Purim

To greet someone on Purim, you can say, “Happy Purim” or use one of the following:

- Chag Purim sameach! (“Happy Purim holiday”)

- Purim sameach! (“Happy Purim”)

- Chag sameach! (“Happy holiday”)

Is Purim in the Bible? The story of Purim

Yes, Purim is based on the story recorded in the Book of Esther in the Bible (note: the Book of Esther is in the third section of the Hebrew Bible known as Ketuvim, “Writings,” but it is not in the Torah which is the Five Books of Moses).

The story is set in ancient Persia during the reign of King Ahasuerus who began to rule the empire in 486 B.C.E. In a nutshell, it’s the story of how a Jewish woman named Esther became queen of Persia and saved her people from annihilation at the hands of a hate monger known as Haman. The story also shows how antisemitism is not a modern phenomenon but stretches all the way back to Biblical times.

The story opens in the third year of Ahasuerus’ reign when he is hosting a lavish, six-month banquet for his servants, the nobility, the army, and all of the Persian people to show off his wealth.

To impress his officials, Ahasuerus called on his queen, Vashti, to appear before them and show off her beauty. When Vashti refused, the king didn’t know what to do. He asked his close advisors, who told him that her personal insult of the king was really a matter of national concern. In Ahasuerus’ kingdom, it seemed that no one was actually in control because the king was so easily persuaded by the advisors around him.

So, at the suggestion of his advisors, Vashti was executed, and the king next conducted a search for the most beautiful virgin in the country to fill the role of queen.

One of the young women presented to the king was Esther who was orphaned at a young age and adopted by her cousin Mordechai. Mordechai was a descendant of a man named Kish from the tribe of Benjamin, who was exiled from Jerusalem over 100 years earlier.

Esther and Mordechai lived in Shushan, the capital of the Persian kingdom, which was the seat of the Persian government and where Mordechai worked in the palace of the king.

Esther won the king’s favor and he made her Queen of Persia. However, at the instruction of Mordechai, she did not tell anyone, including the king, that she was Jewish.

For that matter, Mordechai seemed to have kept his Jewish background a secret from his coworkers at the palace as well. But he couldn’t keep it a secret forever. When King Ahasuerus appointed Haman as his chief advisor, Mordechai refused to bow down to him.

The king’s servants wanted to know why Mordechai didn’t bow down to Haman, and Mordechai explained it was because he was a Jew.

Haman became enraged at Mordechai upon learning this, and he plotted to destroy all the Jews of Persia. Since Persia was a vast empire with 127 countries and provinces, Haman’s plan effectively was to destroy every Jew on the planet.

To determine when he should attack, Haman cast lots, or “pur” in Persian. That’s how the holiday of Purim got its name and the date was set for 11 months later. Haman was so eager to carry out his evil plan that he even built a special gallows on which to hang Mordechai.

Haman also didn’t have a hard time selling his genocidal plan to the king. He started by giving Ahasuerus a truthful and harmless description of the Jews: “There is a certain people, scattered and dispersed among the other peoples [in the kingdom] and their laws are different from those of every people.”

But he put a dual loyalty twist on it that antisemites throughout history have continued to use: “They do not obey the king’s laws and it is not in Your Majesty’s interest to tolerate them.”

With the king’s agreement, Haman sent out a decree to annihilate the Jews throughout the entire Persian empire. Mordechai begged Esther to intervene in order to save the Jews. She was reluctant, because anyone who approached the king uninvited could be put to death!

But Mordechai persisted and helped her realize that perhaps it was for this very moment that she was made queen. Thus, Esther heeded her call to action. In a brilliant move, Esther invited Ahasuerus and Haman to a banquet in the royal palace. At the meal, she made a request: to have another banquet the next day with the same dinner guests.

The king must have been wondering what was going on. He could see that she was troubled and told her that she could have anything she wanted. Maybe he wondered why Haman was invited. Was there a palace coup in the works? Was something romantic going on between Esther and Haman?

At the second banquet, Esther finally burst out with the truth: She was Jewish and her entire nation would be annihilated at Haman’s command!

She asked Ahasuerus to reverse the decree. The king was enraged but could not rescind Haman’s decree because of a rule in the kingdom — once a law was on the books, it couldn’t be retracted.

So, the king first ordered that Haman be hanged on the very gallows he had prepared for Mordechai. Then, the king issued a new decree: letters were sent out to all the provinces, giving the Jews the right to defend themselves against their enemies.

Consequently, the Jews defeated their enemies, and the day on which the Jews were to be destroyed turned into a day of victory and joy. Therefore, the Jewish people “observe the 14th day of the month of Adar and make it a day of joy and feasting, and an occasion for sending gifts to one another” (Esther 9:19).

Why do we celebrate Purim? The holiday’s “hidden” meanings

At the most basic level, on Purim we are celebrating the saving of the Jews of Persia from Haman’s evil decree. On the surface, judging by the costumes, drinking and funny skits, Purim might seem like a completely joyful and silly holiday, but it also has deeper messages. Here are three of them:

1. Was God really “absent” from the story of Purim?

The Book of Esther is one of only two books in the Hebrew Bible that does not contain the name of God (the other is “Shir HaShirim,” the Song of Songs).

In the Five Books of Moses and the Prophets, God often plays an active role in the story, is in frequent communication with the Jewish people, and performs big miracles for them. For example, in the Passover story (contained in the Book of Shemot/Exodus), God splits the sea and sends 10 plagues to Egypt.

By contrast, the Book of Esther portrays a Jewish community that must rely on their own skills and political savviness — not divine salvation — to be redeemed. Much ink has been spilled in the commentaries over why God is absent from the text.

On the one hand, there is the idea that the story is set in a time of “hester panim,” when God is “hidden” or concealed from the world.

The very name of the holiday, “Purim” (“Lots”), suggests that the Jews were merely saved by the “luck of the draw” or a “roll of the dice.” In the end they survived a terrible moment in history, but God was seemingly absent and the story could have turned out very differently.

On the other hand, God could have appeared absent, but was really working “behind the scenes” to bring about the Jewish people’s salvation. According to this interpretation, God was not mentioned but was a “hidden hand” behind the events.

As Dovid Zaklikowski of Chabad wrote: “In contrast to the overt miracles of the holidays of Passover, Hanukkah and other Jewish holidays, the miracle of the holiday of Purim was disguised in natural events… Only after the fact, when one looks at the entire story does one realize the great miracle that transpired.”

2. We all have a mission and it’s up to us to carry it out!

A critical turning point in the Purim story is in Chapter 4 when Mordechai asks Esther to intervene on behalf of the Jewish people. Esther initially pushes back, noting that anyone who approaches the king without having been summoned could face the death penalty.

Mordechai then replies to Esther with the famous words:

אִם־הַחֲרֵ֣שׁ תַּחֲרִ֘ישִׁי֮ בָּעֵ֣ת הַזֹּאת֒ רֶ֣וַח וְהַצָּלָ֞ה יַעֲמ֤וֹד לַיְּהוּדִים֙ מִמָּק֣וֹם אַחֵ֔…וּמִ֣י יוֹדֵ֔עַ אִם־לְעֵ֣ת כָּזֹ֔את הִגַּ֖עַתְּ לַמַּלְכֽוּת

“If you are silent and you do nothing at this time, somebody else will save the Jewish people… And who knows, perhaps you became Queen for this very moment” (Esther 4:14).

Commenting on this, Rabbi Jonathan Sacks wrote, “Wherever we are, sometimes [God] is asking us to realize why He put us here, with these gifts, at this time, with these dangers, in this place… Even [when God appears hidden], if you listen hard enough, you can hear [God] calling to us as individuals, saying, ‘Was is not for this very challenge that you are here in this place at this time?’”

In the Purim story, Esther has the courage and wisdom to heed this call, and as a result, the Jewish people were saved. Purim reminds us to follow in Esther’s footsteps and rise to the occasion when we are called to do so as well.

3. There is a “Haman” in every age.

Haman is identified in the Purim story as the “Agagite,” meaning he is a descendant of Agag, king of the Amalekites. The Amalakites were archenemies of the Israelites.

Rabbi Yitz Greenberg explained that in Jewish tradition, Amalek does not merely refer to the original Bedouin tribe that attacked the Israelites just after they left Egypt, but “symbolizes evil incarnate, a force seeking to wipe out the Jews.” As Amalek’s direct descendant, Haman literally embodies this evil force.

Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik explained the persona of Amalek this way:

“The mere existence of a Jew…irritates Amalek, and his hatred can erupt suddenly and violently and be translated into mass murder. The very presence of a Mordechai arouses Haman; he just can’t bear him. As Haman clearly declared (Esther 5:13): ‘Yet all this [honor] is worth nothing to me, as long as I see Mordechai the Jew sitting at the king’s gate.’”

“Whether Amalek is Fascist (Hitler), Communist (Stalin), absolute capitalist, radical terrorist or even American super-patriot, the Jew becomes the target of his irrational and total hatred,” Greenberg wrote. Although some Jews “have been uncomfortable with this idea, the tradition has insisted that as long as an Amalek exists, the Jews are unsafe.”

At a time that antisemitism has reached alarming new heights in the U.S. and globally, the idea that hatred against Jews is a perennial problem resonates a bit more this year. As depressing as this is, Purim inspires us to have courage and take action with the hope of overcoming our enemies, as Esther and Mordechai did.

Is Purim a Jewish version of Halloween or Mardis Gras?

No. Because Purim involves dressing up in costumes, wearing masks, drinking and partying, some describe it as the “Jewish Halloween” or “Jewish Mardis Gras.” While it is true that the three holidays have some overlap, Purim is not the Jewish equivalent of Halloween or Mardis Gras.

Unlike Halloween and Mardis Gras, Purim is rooted in Jewish tradition, commemorating the ultimate victory of the Jews of Persia over their enemies, and the brilliant maneuvering of the Jewish heroes Esther and Mordechai who made it all happen. Additionally, Purim offers deeper messages about the role God plays in human events, fulfilling our personal missions, the problem of antisemitism and taking courageous action, and more.

Why do we dress up on Purim?

The tradition of dressing up for Purim dates back centuries, possibly to 14th-century Italy. There are a number of deeper meanings behind this long-standing custom. Here are three of them:

- The hidden nature of the miracle: According to Rabbi Richard Jacobs, “One of the deeper reasons for this custom is that the entire miracle of Purim was clothed in natural happenings… There isn’t even an explicit mention of God’s name in the Megillah.” The name “Esther” means “hidden,” hinting at “the hidden nature of the miracle,” he added.

- Concealing our true identities: Wearing costumes and masks highlights the theme in the Megillah of concealing and revealing our true identities. Esther keeps her Jewish identity a secret, and wears a “mask” to blend in with the Persian court, until she reveals her Jewish identity at the perfect time. Additionally, Mordechai does not reveal that he is a relative and friend of Esther’s (until Esther reveals it to the king at the end).

- The special role of clothing: Clothing plays a special role in the Purim story — many of the characters “dress up” in different types of clothes at various points. Mordechai puts on sackcloth and ashes upon learning of Haman’s decree (Esther 4:1), and is later paraded around the city square wearing Ahasuerus’ royal garments (6: 8-11). Plus, Esther puts on her royal apparel before approaching the king (5:1).

Purim basics

- Mishloach manot (Purim gift baskets) — Literally, “sending of portions,” these are gifts of ready-to-eat foods and drinks that are sent to friends and neighbors. The origin of this practice is Esther 9:22 in which Jews are instructed to observe Purim “as days of feasting and merrymaking, and as an occasion for sending gifts to one another and presents to the poor.” Mishloach manot typically include wine or grape juice, hamantaschen, snack foods, sweets or fruits — according to the Shulchan Arukh, each gift must contain at least two different types of food.

- Hamantaschen — Customary in Ashkenazi Jewish homes, these are 3-cornered pastries filled with jams, chocolate, nutella or other types of filling. The triangular pastry could symbolize Haman’s 3-cornered hat. Meanwhile, Mizrahi Jews traditionally bake ma’amouls, cookies stuffed with nuts or dates.

- Purim shpiel — This is a humorous skit or play that is performed in costumes. It can be a funny dramatization of the Purim story or a performance on almost any topic. The Purim shpiel often pokes fun at the people or culture of the community in a lighthearted way.

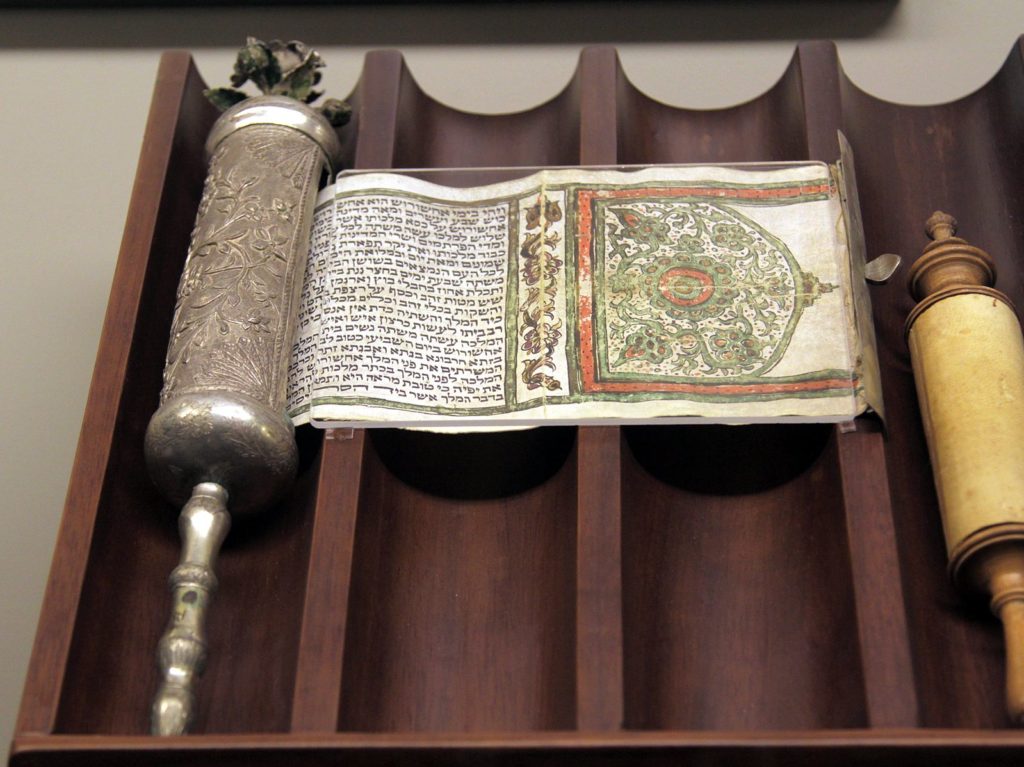

- Megillah (“Scroll”) — The Megillah refers to the Book of Esther that we read on Purim. We read the Megillah twice, once at night and once during the day, using a special cantillation that is used only for the Book of Esther.

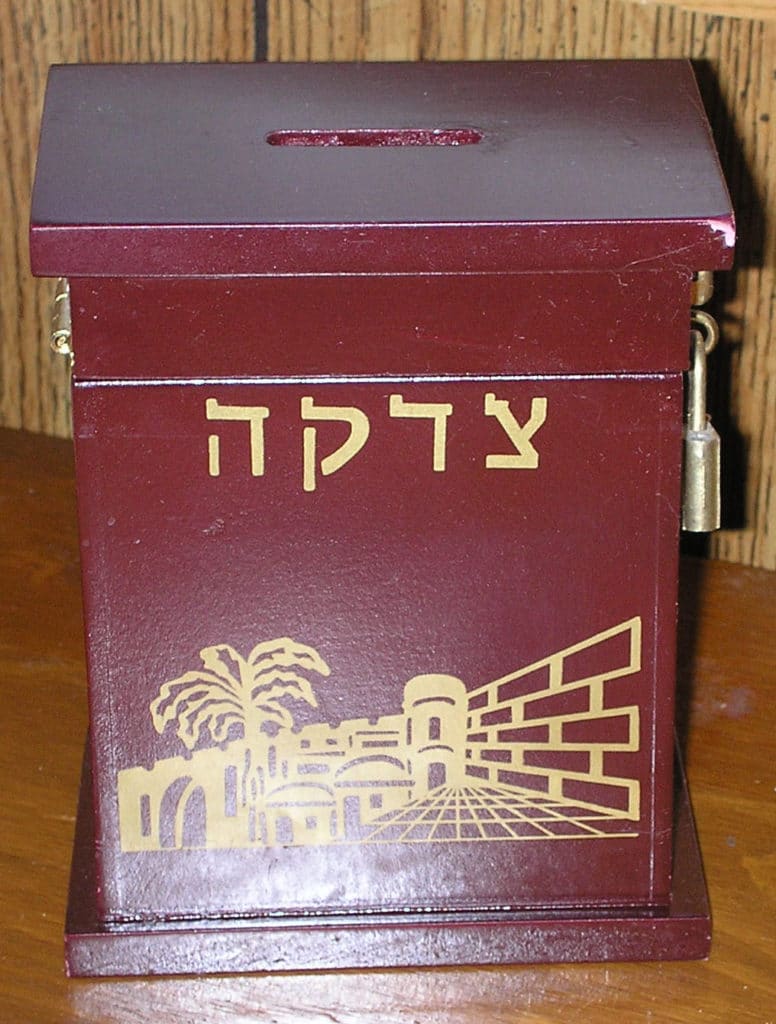

- Matanot l’evyonim (“gifts to the poor”) — In addition to reading the Megillah, sending mishloach manot and having a festive meal, a fourth mitzvah (commandment) of Purim is matanot l’evyonim (giving to the poor). According to the Shulchan Arukh, everyone must give at least two gifts to two individuals in need, and the obligation can be fulfilled through any type of gift (such as money, food, drinks or clothing). In many communities, it is customary to donate what is called machazit hashekel (“half-shekel”) money, in memory of the half-shekel that everyone in the Jewish community donated in ancient times during the month of Adar for the upkeep of the Temple.

Purim Torah readings:

- Shemot (Exodus) 17: 8-16, which is the story of Amalek’s attack on the Israelites in the wilderness.

- Megillat Esther (The Book of Esther)

Purim songs:

Shoshanot Yaakov (“The Rose of Jacob”):

It is customary to recite the Shoshanot Yaakov hymn after the Megillah reading. “Shoshanah” (meaning “rose”) is a reference to the city of Shushan, and “Shoshanot Yaakov” refers to the Jews of Shushan.

שׁוֹשַׁנַּת יַעֲקֹב צָהֳלָה וְשִׁמְחָה בִּרְאוֹתָם יַחַד תְּכֵלֶת מָרְדְּכַי

תְּשׁוּעָתָם הָיְיִתָ לְנָצַח וְתִקְוָתָם בְּכָל דּוֹר וָדוֹר

לְהוֹדִיעַ שֶׁכָּל קוֹוֶיךָ לֹא יְבוֹשׁוֹ וְלֹא יִכָּלְמוּ לָנֶצַח כָּל הַחוֹסִים בָּךְ

אָרוּר הַמָּן אֲשֶׁר בִּקֵּשׁ לְאַבְּדִי

בָּרוּךְ מָרְדְּכַי הַיְּהוּדִי

אֲרוּרָה זֶרֶשׁ אֵשֶׁת מַפְחִידִי

בְּרוּכָה אֶסְתֵּר בַּעֲדִי

וְגַם חַרְבוֹנָה זָכוֹר לְטוֹב

The Jews of Shushan beamed with joy

when they beheld Mordechai robed in royal blue.

You, God, have always been our deliverance,

our hope in every generation.

Those who place their hope in You

will never be ashamed.

Those who trust in You will never be disgraced.

Cursed be Haman, who sought to destroy us

Blessed be Mordechai the Jew.

Cursed be Zeresh, the wife of [Haman]

Blessed be Esther, our protector.

And may Charvonah also be remembered for good.

Chag Purim (“Festival of Purim”):

This is the traditional children’s song for Purim.

חג פורים, חג פורים

חג גדול ליהודים

מסכות, רעשנים

שירים וריקודים

הבה נרעישה

רש רש רש

הבה נרעישה

רש רש רש

הבה נרעישה

רש רש רש

ברעשנים

חג פורים, חג פורים

זה אל זה שולחים מנות

מחמדים, ממתקים

מגד מיגדנות

Festival of Purim

Festival of Purim

A big festival for the Jewish people

Masks, noisemakers, songs and dances.

Wind your noisemakers, “rash rash rash”

Wind your noisemakers, “rash rash rash”

Wind your noisemakers, “rash rash rash”

With your noisemakers.

Festival of Purim

Festival of Purim

We send gifts to one another

Treats, sweets and other nice things.

Wind your noisemakers, “rash rash rash”

Wind your noisemakers, “rash rash rash”

Wind your noisemakers, “rash rash rash”

With your noisemakers.

“An Encanto Purim (We don’t talk about Haman)” by The Maccabeats:

“Purim Song” by The Maccabeats:

Originally Published Feb 17, 2022 09:08AM EST