In 1492, the mass expulsion of Jews in the Spanish Inquisition created waves of refugees throughout Europe and the Middle East. As Sephardic Jews from Spain intermingled with Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern Europe, people became confused about which traditions and rules to follow. Two rabbis rose to settle the matter. Though these two men were from different traditions and never even met, their conflict and collaboration, defined Judaism for half a millennium.

The Jewish oral tradition represents the collected wisdom of rabbis over thousands of years, interpreting the Torah, arguing, and building a consensus on what it means to be Jewish. These rules, called Halakha, cover everything from prayers and festivals, to dietary and marriage guidelines, to procedures in court. They defined and shaped the entirety of Jewish life for millions of people. But, by the start of the 16th century, the tradition was in trouble. Disputes between Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews, arguments between rabbis about the correct opinions, an explosion of new interpretations of the Torah, and a rise in spiritualist philosophies like Kabbalah meant that nobody could agree which opinions were right or which rules to follow. In 1522, Rabbi Yosef Karo decided to fix this.

Born in Spain four years before the expulsion of the Jews, Karo eventually settled in Safed, a holy city near the Sea of Galilee. A mystic and a scholar, Rabbi Karo spent twenty years compiling thirty-two different Jewish authorities into a catalogue of Jewish Law that he called the Beit Yosef. When there was disagreement, as there frequently was, he went with majority rule between the three most prominent scholars: the Rif, the Rosh, and the Rambam.

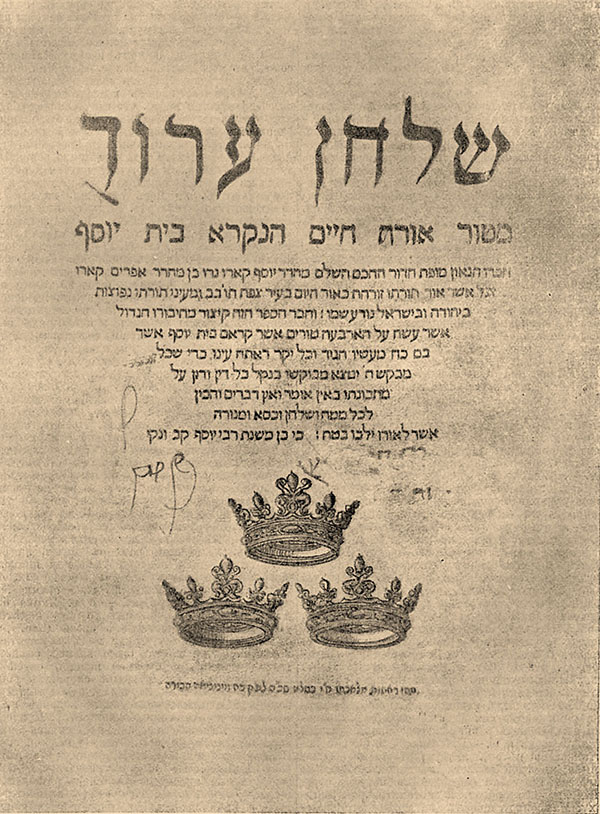

Although the Beit Yosef was a work of astonishing scholarship, it was also very, very long. So Rabbi Karo created a summary that listed the decisions from the Beit Yosef, defining once and for all what he called “the fixed, final law.” It was like SparkNotes for two thousand years of Jewish oral tradition. Rabbi Karo called it the “Shulchan Aruch,” Hebrew for “A Set Table.”

While many Jewish scholars embraced the brilliance and utility of the Shulchan Aruch, a fierce backlash arose. Prominent rabbis decried Karo for streamlining Jewish law and disregarding the disagreements that were a central feature of Halakha. Others protested that Karo’s choice to go with majority rule between two Sephardic rabbis and only one Ashkenazi rabbi strongly favored Sephardic interpretations, a serious problem for Ashkenazi Jews who were not willing to give up hundreds of years of unique customs.

Luckily for Ashkenazi Jews, Rabbi Karo wasn’t the only scholar working on a unified code of Halakha. Rabbi Moses Isserles was a brilliant scholar of Torah who founded a yeshivah in Kraków, Poland. He too recognized that the oral tradition had become overly confusing, saying of the great scholars “One says this and another says that. Time comes to an end, but their words are endless.” While Rabbi Karo was writing the Beit Yosef, Rabbi Isserles was compiling Ashkenazi Halakha into a book titled the Darkei Moshe. He was nearly finished with his masterpiece when Karo’s Shulchan Aruch arrived in Poland.

The Shulchan Aruch created a dilemma for Rabbi Isserles. Publishing the Darkei Moshe would reassert Ashkenazic tradition, but exacerbate the chaos of contradictory rulings. He faced a difficult choice: accept Rabbi Karo’s conclusions and lose centuries of Ashkenazi traditions, or publish a competing book and risk a schism. Rabbi Isserles instead came up with a third approach.

Recognizing that Jewish unity was essential, Rabbi Isserles abandoned the Darkei Moshe and instead, used his knowledge to create a series of additions to Rabbi Karo’s work. Since Karo had called his text “the set table,” Isserles called his additions the Mapah or “tablecloth.” For any laws in the Shulchan Aruch that were different for Ashkenazis, Isserles added glosses that explained the variances. Thus, Rabbi Isserles preserved the Ashkenazi tradition without creating disunity. Isserles then printed the Shulchan Aruch with both Karo’s original text and his additions, consolidating the two traditions into one book. Rabbi Isserles described the text as setting out “the proper order of all the laws… in a manner easily comprehensible to every man, be he small or great.” By abandoning his own book and instead combining his knowledge with Rabbi Karo’s, Rabbi Isserles guaranteed the continuation of the Ashkenazi tradition, while lending his wisdom to the combined text.

This new Shulchan Aruch, complete with its “tablecloth,” quickly became the definitive text on Jewish Law, a text that united Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jews. It was studied in yeshivas around the world, and later scholars added additional glosses and commentaries, placing their own dishes on the table that Rabbi Karo set. It remains a guiding light, a constitution of the Jewish people, nearly as important as the Torah or the Talmud.

The story of the Shulchan Aruch represents the best of Jewish tradition. It marks a dedication to scholarship, combined with an appreciation of practicality; a unified text that still incorporates disagreement, and a recognition that, at the end of the day, working together makes us all stronger.