Listen:

We’re curious…

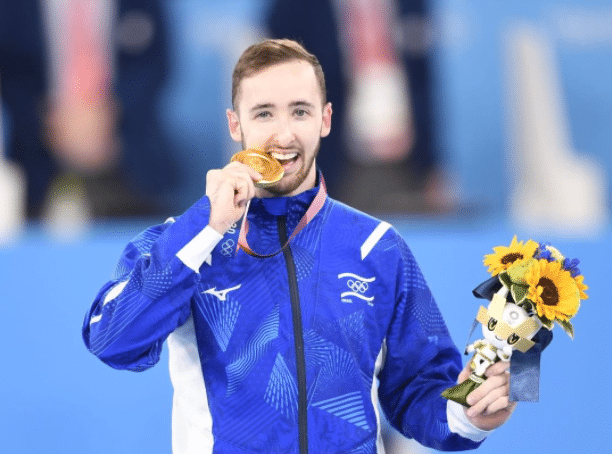

Israeli gymnast Artem Dolgopyat won a gold medal last week at the Tokyo Olympics, becoming the second Israeli ever to take home an Olympic gold. “I don’t know what to say. I made history,” Dolgopyat said immediately following his win. “I did it all for the people of Israel. I am so proud to represent Israel.” Upon returning to Israel, Dolgopyat received a hero’s welcome with champagne, drums and blasts of the shofar. This was a remarkable moment in the history of the State of Israel.

And, just as Israel began celebrating its newest sports hero, the story about Dolgopyat’s victory evolved into a completely different conversation…about Dolgopoyat’s inability to get married in Israel.

Dolgopyat’s mother, Angela Bilan, said in an Israeli radio interview that her son is unable to marry his girlfriend of three years in the country because he is not Jewish according to traditional Jewish law. Israel’s Law of Return grants automatic citizenship to anyone who has a Jewish grandparent; however, the Chief Rabbinate (which controls marriage in Israel) says that only those who have a Jewish mother, and Orthodox converts, are Jewish. Only Dolgopyat’s father’s side is Jewish.

Bilan’s comments sparked a renewed debate in Israel over the country’s marriage laws and a question that Israelis have always grappled with: Who is a Jew? (Watch our video that we created with the Z3 Project exploring this question.) Is a Jew someone whose mother is Jewish (as traditional Jewish law defines it), someone who has a Jewish grandparent, or someone who celebrates Jewish holidays or merely feels connected with Judaism? In light of the current conversation in Israel, we wanted to unpack Israelis’ diverse perspectives on Dolgopyat’s marital situation and how Israel’s current marriage laws came about.

Great to see the #bbcolympics commentator so excited. What a wonderful routine by Artem Dolgopyat and a first ever medal in #gymnastics. Hard work and dedication pays off . You are a model for every Israeli child 🇮🇱🥇 pic.twitter.com/A2A8W8G25g

— Ohad Zemet (@OhadZemet) August 1, 2021

How did Israel’s marriage laws come about?

The roots of Israel’s marriage laws go back to the beginning of the Jewish state when a debate emerged over what the Jewish character of the new country would mean. Was Judaism a religion like Christianity and Islam, or was Judaism a nation, like the Germans or the French? How would standards of kashrut be expressed? What would the education system look like? What would Shabbat look like in a Jewish state?

These questions were addressed in 1947, leading up to the creation of the State of Israel. Members of the haredi Agudath Israel movement wanted to preserve religious observance in a largely secular Zionist society; soon-to-be prime minister David Ben-Gurion agreed to their requests in order to present a united front ahead of the UN’s partition plan vote. This became known as the “status quo agreement,” which includes the following (and hasn’t changed much since):

- Shabbat would be a national day of rest for the Jews, with Christians and Muslims having their own days.

- Kashrut would be observed under state auspices.

- Religious courts (Jewish for Jews, Christian for Christians, and Muslim for Muslims) would decide aspects of personal status, such as marriage, divorce and burial.

- Religious educational systems which already exist would be recognized by the Jewish state.

When it comes to marriage, the implication of this is that Israelis may only marry through the religious court of their religion. Therefore, Jews must marry through the Rabbinate, while Muslims, Catholics and Druze must marry through their respective religious courts (all of which are funded by the state). That is why anyone who is not considered Jewish by the Chief Rabbinate — along with gays and lesbians, converts to Judaism through non-Orthodox denominations, and various others — cannot get married in Israel. To work around this, many couples travel abroad to have a civil marriage which is then recognized by the state.

Although religious courts preside over marriage and family matters in many other countries in the Middle East, this arrangement is extremely uncommon in Western democracies. Nechama Goldman Barash, an educator at the Matan and Pardes Institutes, explained in a Jerusalem Post op-ed that “Marriage in Western democracies is a civil, not a religious matter.” She cited the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the U.N. General Assembly in 1948, which states that “men and women of full age, without any limitation due to race, nationality or religion, have the full right to marry and to found a family… They are entitled to equal rights as to marriage, during marriage and at its dissolution.”

A majority of Israelis favor a change to the country’s marriage laws and the rabbinate’s monopoly over religious issues. According to a new survey by the Hiddush Association for Religious Freedom and Equality, 65% of Jewish Israelis support the introduction of civil marriage in Israel. However, opponents of civil marriage argue that this would dilute Israel’s Jewish character.

Goldman-Barash explained the rationale behind this view: “For the Jewish people, marriage historically has defined and sustained the homogeneity of the Jewish people. Supervision of marriage, divorce, conversion and religious identity by the state Rabbinical Court [maintains] this homogeneity.” She added that keeping marriage and divorce under the control of the Orthodox Rabbinate allays the concern that women could “remarry in violation of halacha with the spread of mamzerut (children born from forbidden relationships) as a possible consequence.”

The Tzohar rabbinical organization offers an alternative marriage registration service — that still meets the Rabbinate’s halachic standards — for couples who do not want to get married through the Rabbinate. Tzohar founder and chair Rabbi David Stav told Israel Hayom, “We know very well that a large majority of Israeli couples, both religious and secular, will choose to have a halachic wedding if the process and experience are respectful of their needs and made accessible to them.” Tzohar has helped arrange over 60,000 wedding ceremonies since it was founded in 1996.

Although the question of religion and state is one that many Israelis feel very strongly about one way or another, it often gets overshadowed by other issues. A survey conducted by the Israel Democracy Institute in 2019 indicated that “questions pertaining to religion and state are not a high priority when deciding who to vote for.” The issues that take the lead are economic and social issues (36.7%) and security and foreign affairs (36.2%). Just 15.5% of Jews marked religion and state as an “extremely important” issue.

Diverse perspectives from Israelis

Some Israeli politicians pledged that they would take steps to change marriage laws in Israel and allow Dolgopyat to get married in Israel. Foreign Affairs Minister and Alternate Prime Minister Yair Lapid told The Jerusalem Post, “It’s intolerable that someone can fight on our behalf in the Olympics, represent us and win a gold medal and not be able to get married in Israel.”

Similarly, Labor leader Merav Michaeli said, “Just like we broke the kosher certification monopoly, the time has come to end the monopoly of marriage in Israel.” Michaeli was referring to a plan announced last month by Israel’s Religious Affairs Minister Matan Kahana to overhaul Israel’s kosher certification industry and enable independent agencies to issue kosher licenses.

However, Haredi politicians such as Shas party leader Aryeh Deri expressed the opposite view, arguing that these proposed changes would end the Jewish character of the state. “Winning a medal doesn’t make [Dolgopyat] Jewish,” Deri told The Jerusalem Post. “Our laws are consistent: For 73 years, marriage in this country has been run by Jewish law.”

The current debate inspired by Dolgopyat is a continuation of tensions between the Haredi government and the new government since it took office two months ago. Last month, in response to the government’s proposed reforms of the kosher certification industry, United Torah Judaism leader Moshe Gafni denounced Kahana (who announced the proposal) as “Antiochus,” the villain of the Hanukkah story who led a campaign to ban Judaism.

However, Jerusalem Deputy Mayor Haim Cohen of the Shas party offered a different perspective. In an op-ed in the Haredi weekly newspaper “Mishpacha” that was shared widely on Haredi social media, Cohen put forth the radical idea that it could be time for Israel’s religious and state functions to separate. He argued that if “the two systems are separated, the state will have no say in halachic matters” and religious courts could have autonomy over their own system, free from the influence of Israel’s secular institutions. Cohen explained that the religious courts “are subordinate to some degree to the secular state system” and that their decisions can be appealed and revisited by Israel’s Supreme Court.

Cohen further argued that the current situation is harming public perceptions of the Haredi community. At the same time, the Haredi community does not use the state’s religious functions because they do not meet their religious standards: “We’re seen as paternalistic and coercing our views on the public, even as we ourselves are uncomfortable with the existing situation.”

Meanwhile, some Orthodox rabbis in Israel, like Hayim Leiter, expressed their support for changing marriage laws to include people like Dolgopyat. In a Times of Israel blog post, Leiter argued: “When someone like Dolgopyat has grown up his entire life as a Jew and as an Israeli, the nuts and bolts of Judaism are part of his cultural upbringing… These men and women know about Judaism, the holidays, and most importantly what it means to throw their lot in with the Jewish people. They’ve served in the IDF and feel Jewish in their essence. It’s high time that we treated them that way.”

Similarly, Yaakov Katz, editor-in-chief of The Jerusalem Post, argued in an op-ed that Dolgopyat’s situation shows that “after 73 years of statehood, Israel still does not provide full rights to all of its citizens. Most people read that and think about the Palestinians. In this case though, the reference is to the more than 300,000 Israeli citizens who live here but cannot get married because the Chief Rabbinate and Orthodox halacha do not recognize them as Jewish.” Katz concluded that “marriage is supposed to be a basic right,” adding that Dolgopyat “should be allowed to get married because he is an Israeli citizen. It is that simple.”

The bottom line

While the Israeli-Palestinian conflict typically gets the most attention, it is the conflict between different Jewish communities — and between Israel’s values as a Jewish and democratic state — which are perhaps Israel’s most perilous challenges. For some, defining Jewish identity and who should be allowed to marry in Israel is “of course” based on Orthodox Jewish law; for others, Jewish identity is “of course” more broadly defined.

The conversation about Dolgopyat is an opportunity for the Jewish world to come together to rethink this challenge. For the sake of the relationship between Israeli and World Jewry and the entire Jewish community, we hope Jewish leaders interpret one another charitably and work toward solving these problems together. Instead of “Jew versus Jew,” we can become “Jew with Jew.”

Originally Published Aug 10, 2021 12:03AM EDT