“Oppenheimer” is set to be one of the biggest blockbusters of the summer when it’s released on July 21.

However, Christopher Nolan’s drama will likely not go into detail about the rich Jewish history of J. Robert Oppenheimer and many of the other scientists working on the Manhattan Project.

Before ‘Oppenheimer’ hits the silver screen, here’s a deeper dive into the life of the “father of the atomic bomb” and his Jewish colleagues.

The basics

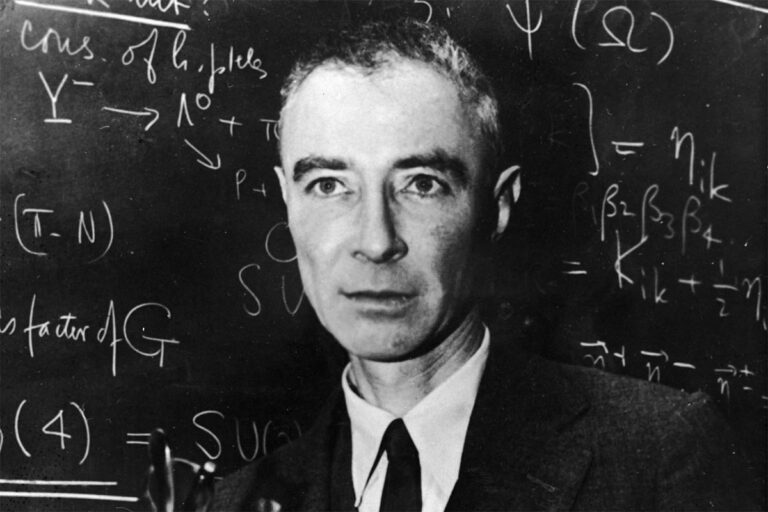

Julius Robert Oppenheimer, best known for leading the research for the atomic bomb as the Director of the Los Alamos Laboratory, was born April 22, 1904, to Ella and Julius Oppenheimer, a Jewish immigrant from Prussia.

Oppenheimer had a privileged upbringing in Manhattan in New York City, with his mother a celebrated painter and his father a prosperous textile importer.

Though the Oppenheimers were not practicing Jews, their experiences were inevitably colored by the rising tide of antisemitism in both Europe and the United States.

“He grew up in a family that was very successful and therefore felt like they had a lot at stake, a lot to protect and to hold on to, and showing their Jewishness was not part of that equation. It seems like that success changed their relationship to their heritage and to Judaism,” Louisa Hall, author of “Trinity,” a novel about Oppenheimer, said.

After completing his studies at Harvard and Cambridge, Oppenheimer was drawn to the hallowed halls of the University of Göttingen in Germany, then the world leader in physics, to pursue his PhD.

Not one to shy away from academic discourse, Oppenheimer often found himself at the heart of robust seminar discussions, so much so that his peers threatened a class boycott unless he dialed back his dominating presence.

Upon securing his doctorate, Oppenheimer returned to the U.S., heading west to lecture at the University of California, Berkeley, and the California Institute of Technology.

After establishing a strong academic presence on the West Coast, Oppenheimer’s career took a significant turn during World War II. In 1941, he was recruited for a top-secret government project, which would eventually be known as the Manhattan Project, and he became its scientific director.

Within four years, in 1945, the Manhattan Project scientists completed the atomic bomb under Oppenheimer’s leadership.

The U.S. first detonated a nuclear weapon during the Trinity test in New Mexico. Less than a month later, the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing over 125,000 people.

Oppenheimer’s Jewish identity: From denial to action

Throughout his life, Oppenheimer experienced episodes of depression; his longtime friend Isidor Rabi attributed this struggle to his denial of his Judaism. Rabi believed that Oppenheimer’s refusal to acknowledge his Judaism led to feelings of isolation and identity issues.

According to Hall, Oppenheimer often pretended the antisemitism around him didn’t exist, dismissing the discrimination he experienced both academically and professionally, as if he were immune to such affronts. He also tended to ignore the slights made toward his Jewish colleagues.

For instance, when Oppenheimer endeavored to secure a post for his colleague, physicist Robert Serber, at Berkeley, department head Raymond Birge rebuffed him, claiming that “one Jew in the department is enough.” Oppenheimer didn’t seem phased by this response.

However, when the Nazis began to take control of Europe, Oppenheimer began feeling rage toward the stripping of rights of Jewish people in Germany. “I had,” he said, “a continuing, smoldering fury about the treatment of Jews in Germany. I had relatives there, and was later to help in extricating them and bringing them to this county.”

Between 1934-6, Oppenheimer also donated 3% of his salary from teaching to fund German physicists fleeing Nazi Germany. But the disturbing developments overseas motivated Oppenheimer to do more than merely donate money.

When World War II began, Oppenheimer joined the Manhattan Project, the team hired to create the first nuclear weapons. In 1943, he became director of the Los Alamos Laboratory, the hub of atomic bomb development.

The role of Jewish scientists in the Manhattan Project

The main goal of the Manhattan Project was to complete the atomic bomb before Germany did. At the outbreak of the war, Germany was considered the leading country for science and innovation, and had focused its best minds on developing bombs and rockets.

Oppenheimer was not the only Jewish scientist who felt compelled to join. Notably, six of the Manhattan Project’s eight leaders were Jewish, and the project’s ranks included hundreds of other scientists, soldiers, and technicians.

A significant number of the Manhattan Project’s key scientists were Jewish refugees from Europe, including Hans Bethe, Otto Frisch, John von Neumann, James Franck, Edward Teller, Klaus Fuchs, and Rudolf Peierls.

Many of them had immigrated to the U.S. after being invited to conduct research at top universities on what would become elements of the atomic bomb.

For instance, Franck, Italian physicist Enrico Fermi (who defected to protect his Jewish wife from Mussolini’s regime), and Jewish physicist Eugene Wigner began their work on the bomb at the University of Chicago.

Hungarian-born Leo Szilard, a Jewish refugee who joined the Manhattan Project, is often recognized as the creative genius behind the bomb due to his role initiating the project at the University of Chicago. Szilard and Fermi patented a potential nuclear reactor design.

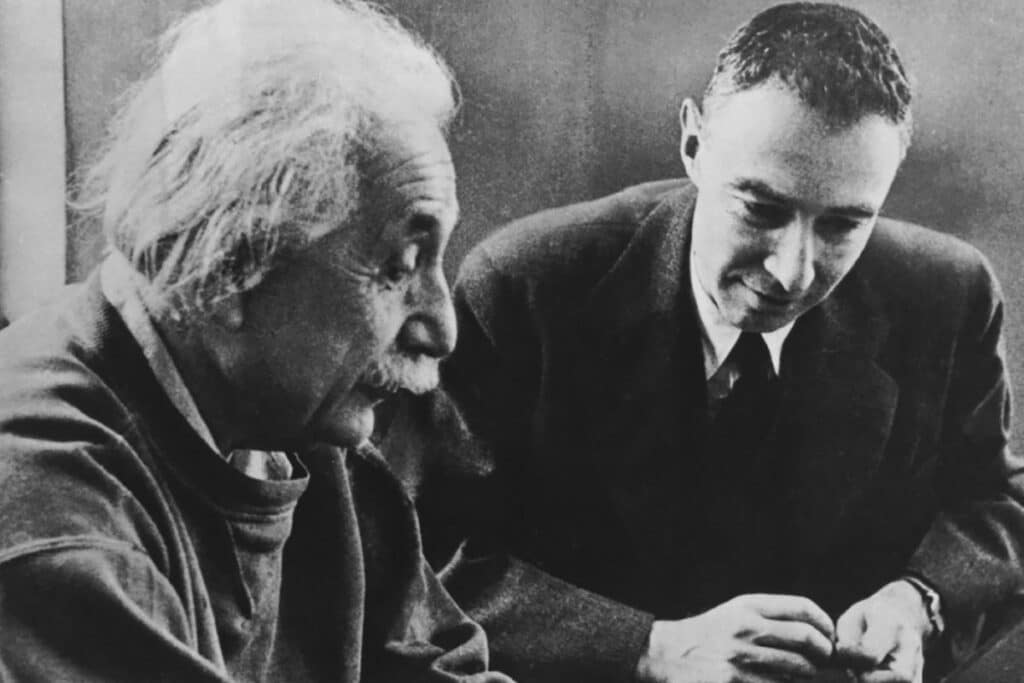

Szilard also persuaded Albert Einstein, a pacifist German Jew who fled Europe when the Nazis took power, to co-author a letter to President Franklin Roosevelt to fund a U.S. nuclear research program, which would become the Manhattan Project.

The Manhattan Project eventually sprawled across the entire country, with significant operations in Los Alamos, New Mexico; at Columbia University in New York; in Berkeley, California; and in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

The involvement of these Jewish scientists was not just an act of survival, but also a crucial contribution to the Allied victory in World War II.

Oppenheimer spent his final years advocating for peace

After spending several years building the atomic bomb, Oppenheimer dedicated the rest of his life advocating for the limitation of its use. Some accounts even suggest that he harbored regrets over creating it.

In 1945, as World War II drew to a close, he met with President Harry Truman to advocate for international stipulations on nuclear weapons. Oppenheimer did not appear remorseful over what happened during World War II, but rather for “the deaths of millions of individuals in some distant apocalypse,” according to historian Paul Ham.

Oppenheimer said: “Mr. President, I feel I have blood on my hands.” But instead of empathizing with the Jewish scientist, Truman reacted harshly, ending the meeting early. He later called Oppenheimer a “cry baby scientist” and said that no one should ever bring “that son of a bitch in this office ever again.”

Following the war, Oppenheimer was appointed chairman of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission’s General Advisory committee. In this role, he underscored that the atomic bomb was instrumental in ending World War II and spared thousands of American lives, but needed to be regulated in the future.

He urged U.S. government leaders to encourage international control of nuclear power and to find ways to limit countries stockpiling nuclear weapons, arguing that atomic weapons posed extreme dangers for future warfare.

“The atomic bomb made the prospect of future war unendurable. It has led us up those last few steps to the mountain pass; and beyond there is a different country,” Oppenheimer said in his 1946 commencement speech.

He also advocated for the U.S. to not begin a nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union — an action which would eventually become his downfall in the McCarthy-era, which perceived him as an enemy of the state.

Due to his stance on a potential nuclear arms race, in addition to his previous associations with communists, Oppenheimer lost his security clearance. This judgment was posthumously overturned in 2022 when the government recognized Oppenheimer as an American patriot.

Oppenheimer died on February 18, 1967, at age 62.

Originally Published Jul 10, 2023 11:00PM EDT