I’m not strictly a historian, but since I play one on this podcast, and I did major in history, thank you very much, I feel totally justified in telling you that there is nothing I find more satisfying than coming across a real, live primary source.

And by “primary source,” I don’t mean a letter or diary entry or court record, though those are great too. No, I’m interested in a primary source that can think for itself and answer direct questions. A human being who inhabited whatever vanished age I’m obsessed with at the moment.

Sometimes, these living primary sources remind me that history can be unbelievably cruel. Broadly speaking, I grew up in an Ashkenazi Jewish community only 50-some years after the Holocaust. So many people I knew had at least one relative who survived… and many more who didn’t.

So when I first got interested in the Kastner trial – the insane, painful, important, complicated story I’m gonna tell you about today – I didn’t just hit the books or read the journal articles or watch the Israeli miniseries about it (though obviously, I did all those things too).

No, I had the privilege of going straight to the source. Or, well, almost straight to the source, since it’s 2022, and primary sources don’t live forever. But my friend Michelle is the grandchild of two Hungarian Holocaust survivors. And when I asked Michelle’s father what he thought of Kastner, he replied, “you mean, the guy who sold Jews for trucks?”

Ouch.

With an epithet like that, I assumed he hated Kastner, seeing him as a Nazi collaborator. But then he said something curious. “The man’s a hero. He personally saved some of my relatives!”

Huh. What??!

All the complexity and pain of the Kastner story, bundled into two sentences. “He sold Jews.” And also, “he’s a hero.” Can both things be true at once? And do any of us have the right or the ability to place any kind of moral judgment on people who lived through the unimaginable?

I’m gonna tell you straight off the bat: this isn’t a feel-good story. It’s a painful, real-life take on the kind of moral dilemmas most of us will – hopefully! – only encounter in a philosophy class. Moral dilemmas are situations in which the decision-maker must consider two or more moral values or duties but can only honor one of them. Which makes them impossibly difficult. No matter which moral imperative wins, another one loses.

Back in my teaching days, I used moral dilemmas in my class constantly. They’re a useful pedagogical tool, designed to make students consider complex issues from every angle. To sharpen critical thinking skills. To hone a student’s moral compass.

But they’re largely – and thankfully – theoretical.

The same cannot be said of the Kastner story, a moral dilemma brought painfully to life in the aftermath of the Holocaust. After all, there’s no playbook for the aftermath of genocide…

Jerusalem, 1952. The four-year-old country of Israel was still trying to figure out how to be a country. A 72-year-old stamp collector and amateur journalist named Malchiel Gruenwald had just published some pretty scandalous accusations in his homemade newsletter, which he distributed at his local cafe.

Scandalous accusations weren’t anything new for Gruenwald – as Israeli historian Tom Segev puts it in his book The Seventh Million, “Every so often someone would threaten to sue him for libel, and Gruenwald would make a public apology.”

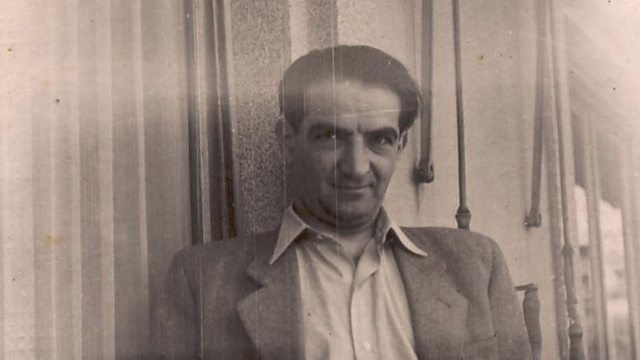

But he had no interest in retracting Issue #51 of his homemade paper, which accused, in the most florid terms, Israel “Rudolf” Kastner, press spokesman for the Israeli Ministry of Commerce and Industry, of being a Nazi collaborator. Of paving the way for the murder of Hungary’s 800,000 Jews, while he used his personal relationships with senior Nazi officials – among them Adolf Eichmann – to save his family members, influential Jews, and people he knew personally. Of profiting from Nazi war crimes. And – perhaps worst of all – for acting as a character witness for SS officer Kurt Becher, the Special Reich Commissioner for all concentration camps, directly leading to Becher’s release from jail.

Oof.

These accusations – though severe – meant very little at first. After all, Gruenwald was a nobody, self-publishing his unverified tirades for a very limited, and often reluctant, readership. The 1950s equivalent of that well-meaning weirdo on your newsfeed who has way too much time on his hands and way too many opinions about aliens.

But, on the other hands, you’d think that a country with a Nazis and Nazi Collaborators (Punishment) Law would take such charges seriously. After all, the 1950 law mandated that anyone found to have committed “a crime against the Jewish people,” “a crime against humanity,” or a “war crime” during WWII could be punished by the death penalty. But those are the sorts of cases that no one in 1950s Israel wanted to pursue. Because early Israelis didn’t like to think too much about the Holocaust. They didn’t like to be reminded of how easily six million had been slaughtered. It was much easier to pretend that the slaughter was somehow the victims’ fault. That stronger, better Jews would have resisted and won.

And it was especially upsetting to think about the Jews who survived through collaboration. If Holocaust survivors were weak, then collaborators were dirty. Better to pretend they didn’t exist at all.

So very few people were ever indicted under this law, and none received the death penalty. Instead, survivors doled out rough justice on the streets, attacking and sometimes killing people they recognized as collaborators.

Now, Kastner had been accused before. A man from his hometown of Kluj would come to all his speeches just to heckle him. And, at the 22nd Zionist Congress in 1946, a representative from the religious Zionist party accused him of misusing half a million dollars set aside for saving Jews. (That’s equivalent to about $7 million in today’s money, by the way, so not a small number of shekels.) And in the wake of the 1950 Collaborator law, the police paid him a visit, asking about his activities in Hungary during the war.

But through it all, Kastner stuck to his story: he was the head of the Hungarian Rescue Committee, which worked in tandem with the Jewish Agency to help Polish and Slovakian Jews flee to Hungary. When the Nazis arrived in Hungary in 1944, he was forced to deal with them, just like all the other Jewish leaders across Europe. But unlike Europe’s other Jewish leaders, he was able to negotiate directly with Adolf Eichmann. By 1944, the Nazis were even desperate enough to propose a plan to let one million Jews in Hungary go free, in exchange for 10,000 trucks to use on the eastern front. The deal fell through for many reasons that could fill a podcast in themselves. But “blood for goods” became a watchword, particularly among critics who saw something grotesque in the “sale” of Jews.

He didn’t manage to save one million. But he did get 1,685 Jews out of Hungary on the so-called “Noah’s Ark” train. Yes, his friends and family. And yes, influential Jews like the uber anti-Zionist, Satmar Rebbe, Yoel Teitelbaum. But also housewives and children. Simple Jews of no import. The train was such a cross-section of society that it became known as “Noah’s Ark.” Even the wealthy Jews who paid for seats did so to cover the cost of the train: $1,000 a head, paid to the Nazis. Everyone knew this story, didn’t they? Kastner was a hero. A man who did all he could.

And maybe if he hadn’t been a government employee, this is the only story we would know about Israel Rudolf Kastner. He was a man in a terrible bind who leveraged what tiny influence he could to save as many Jews as possible. A tiny fraction when set against six million, but not an insignificant one. As we read in the Talmud, in Tractate Sanhedrin, page 37a:

וכל המקיים נפש אחת מישראל מעלה עליו הכתוב כאילו קיים עולם מלא

“He who saves a Jewish life saves a whole world.”

But, Kastner did work for the government. He’d been associated with Mapai, the Labor Zionist party that now ruled Israel, since well before his arrival in Israel. He had designs on being a member of Knesset. When the newspaper Herut picked up on this story, Israel’s Attorney General Chaim Cohen advised Kastner that he either needed to clear his name or resign from his position. A slur against Kastner was a slur against the Israeli government itself.

Kastner had no interest in the trial. Like many survivors, he just wanted to forget everything: what he had seen. What he’d been forced to do. But he wanted a career in politics – preferably in the Foreign Office. And Attorney General Cohen – who, like Ben Gurion, hated the press and was dying to knock it down a peg – was chomping at the bit to prosecute the case. He insisted that “No one can be allowed to say that a senior government official collaborated with the Nazis without there being a response!”

Thus, on the very first day of 1954, began Attorney General v. Gruenwald. The state threw its weight against some unprepossessing old guy, fully expecting him to capitulate in days.

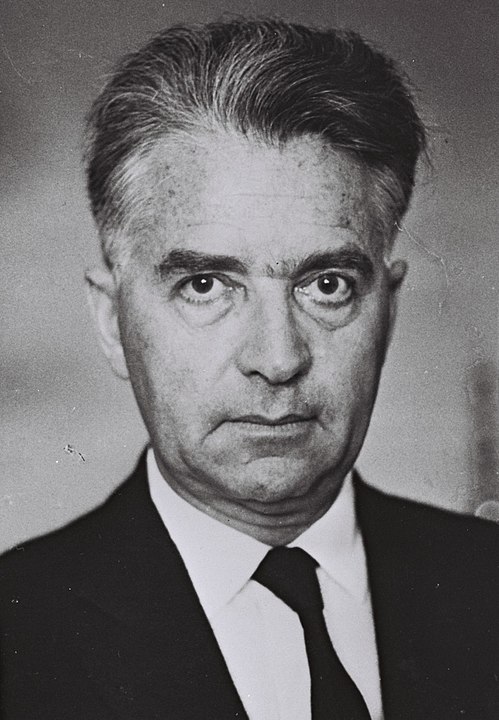

But the state didn’t count on Gruenwald’s brilliant, prickly defense lawyer, Shmuel Tamir. It really didn’t count on Tamir – a die-hard Revisionist, the more aggressive form of Zionism, initiated by Ze’ev Jabotinsky, who had sharply opposed any – using this trial to pick a fight with an entire government full of Labor Zionists. And it really, really didn’t think about what would happen if he won.

So let’s talk about Gruenwald’s defense lawyer, Shmuel Tamir – the man who took apart Rudolf Kastner, and by extension the entire Israeli government. Born Shmuel Katznelson, he was a former Irgun commander who had been such a pest to the British, they’d shipped him off to a prison camp in Kenya in 1947. “Tamir” had been his Irgun codename. (Remember, the Irgun, AKA Etzel, was one of three paramilitary squads in pre-state Palestine. It had serious beef with the Haganah, David Ben Gurion’s paramilitary, which eventually became the IDF. Our Black Sabbath episode has way more context on this – give it a listen if you haven’t already, it’s awesome.)

Katznelson came home to a newly formed state of Israel in July of 1948, changed his name officially to Tamir, and founded the Herut party with our old friend Menachem Begin. (Which is, by the way, why the Herut newspaper broke the story of the trial.) Begin and Tamir reportedly didn’t get along very well, but they had one thing in common: they were not David Ben Gurion’s number one fans, to say the least. In fact, in 1952, Tamir published an article in the Herut newspaper calling Israel’s first PM “the Minister of Treason and Minister of Abomination.” Lovely.

So this libel case felt like a prime opportunity to take Ben Gurion’s party down a peg… or two… or ten. Tamir wasn’t particularly interested in Gruenwald. His motivation was exposing what he saw as the corruption at the heart of the Jewish Agency and the Mapai party – not just in 1952, but during the Holocaust itself.

But Tamir wasn’t merely playing petty politics. (Say that ten times fast!) Over the course of the trial, he raised some uncomfortable and impossible-to-answer questions at the heart of Jewish life since the day the Romans rolled into Judea in 63 B.C.E.

See, when the Jews are oppressed by an outside force – so, you know, for the past two thousand years – there’s often a split in our approach to the enemy. One side advocates for surrender. For doing what you need to do to survive, whether that means negotiating with the Roman emperor or with Adolf Eichmann.

The other side says fight to the death, and don’t give an inch. Like the Sicarii of Roman times, who killed fellow Jews they suspected of not resisting the Romans “enough.” Like the resistance fighters in the forests and ghettos and death camps of Europe, fighting what they knew was a doomed fight.

But here’s the thing. Kastner actually did something amazing. He managed to save 1,685 Jews…Through negotiation with the enemy.

But with Tamir in charge of the defense, Kastner was made out to be the villain. Because Tamir was one of those “fight to the death” radicals. And Kastner had committed the ultimate sin: doing whatever he needed to do to survive.

So Tamir played dirty. He brought in the mother of murdered paratrooper Hannah Senesh, who testified that Kastner had ignored her desperate pleas while her daughter was tortured in captivity. Another paratrooper claimed that Kastner had forced him and his colleague to turn themselves in to the Gestapo, so that they would not foment Jewish resistance and endanger his deals with the Nazis.

Slowly, Tamir crafted the narrative that Kastner actively dissuaded Jews from resisting so they wouldn’t interfere with his relationship to the Nazis… just like the Haganah, and David Ben Gurion, had done during the Mandate years.

Tamir explicitly equated the Haganah’s collaboration with the British to Kastner’s collaboration with the Nazis. He told Kastner: “While your comrades collaborated with the British and you with the Nazis, we were out fighting to save Jews.”

Yikes. Because I’ll remind you: Tamir may have fought the British. But the British weren’t the Nazis, and Mandate Palestine was not 1940s Europe.

It was ugly. Personal. And entirely unfair.

Tamir spun a story that anyone who didn’t resist was complicit. And, Judge Benjamin Halevy made the unusual decision to examine some of the witnesses himself. He asked survivors painful and difficult questions, like, “if you had known you were on the train to Auschwitz, would you have tried to escape? Would you have refused to get on the train to begin with?”

Counterfactuals from a person who had no idea what these survivors had been through. How could he have?

The trial grew from a nothing little libel case to a national sensation, and the press went wild.

The Herut newspaper, delighted to stomp all over Mapai, published headlines like “The Jewish Agency Quashed News of the Extermination in Hungary.” Another newspaper, HaOlam Hazeh, owned by an Irgun veteran named Uri Avneri, more or less became a mouthpiece for Tamir.

Here’s Uri Avneri discussing his newspaper’s role in the Kastner trial: “Shmuel Tamir came to the printing house at night, looked over the material, made some comments, requested some changes. But although I was in close contact with Tamir and we talked every day, our perceptions became more and more diverse. In my view, his approach was primitive, simplistic. He did not comprehend the more important political entanglements.”

Easy to say now, with the benefit of hindsight. But at the time, Tamir – a Revisionist – made Kastner a symbol of “the other side:” the weak, groveling, complicit Jew who participates in his own degradation.

Worst of all was Kastner’s testimony exonerating SS Officer Kurt Becher.

Becher was… not a great guy. Here’s how American journalist and screenwriter Ben Hecht describes him in his 1961 book about the trial, the incredibly controversial Perfidy: “He was appointed by Himmler as Chief of the Economic Department of the S.S. in Hungary. ‘Economic Department’ was either a pompous or humorous locution… for the Germans employed in extracting the gold fillings fom millions of teeth of dead Jews; in cutting off the hair of millions of Jewesses before killing them; and in figuring out effective methods of torture to induce the Jews awaiting death to reveal where they had hidden their last possessions.”

Hecht doesn’t pull his punches. And it’s worth noting that as an ardent supporter of the Irgun and a fan of Shmuel Tamir, he makes absolutely no secret that he hates Rudolf Kastner.

But Hecht and Tamir didn’t invent the signed affidavit that Kastner presented to a local denazification court after the war, in which he wrote “there can be no doubt that Becher was one of the few SS leaders to take a stand against the extermination program and who made an attempt to save human lives… I never for a minute doubted his good intentions…. I make this statement not only in my name but also on behalf of the Jewish Agency and the World Jewish Congress.”

Wow.

Not only had Kastner been caught in an outright lie – from the start, he had vehemently denied testifying for Becher – but he had done so in the name of the Jewish Agency and the World Jewish Congress. And though the Jewish Agency witness swore up and down that Kastner wrote that final line without anyone’s knowledge or permission, Tamir implied that he too was lying. Everyone was implicated. The Jewish Agency. The ruling party. Ben Gurion. And, of course, Kastner himself.

It took Judge Halevy nine months to consider the evidence: thousands of pages, sixty witnesses, testimony in six languages. Because there is no jury system in Israel, he did all this alone. His 274-page verdict was damning. Three of Gruenwald’s claims were true, he ruled. Kastner had collaborated. He had “paved the way for the murder of Hungarian Jewry.” He had testified for Kurt Becher. He had not been found to have profited from the Nazi looting of Jewish valuables.

Halevy went so far as to say that Kastner had “sold his soul to the devil” and wrote “It seems to me that from a public, moral, and even legal point of view, Kastner’s behavior… is the same as turning over the majority of Jews to their murderers to benefit a few.”

Again, the press went crazy. Every paper had an angle – or, as we might say today, a “hot take.” To put it lightly: most of these were pretty un-nuanced. I can put it more strongly, but I’d rather not.

The Revisionist Herut published pictures of Kastner with the caption “Eichmann’s partner,” glossing over the fact that, actually, Revisionists in Budapest had supported Kastner. Poor Kastner became the Revisionists’ punching bag in their fight against the ruling party.

The Communist paper, conveniently forgetting the Hitler-Stalin pact, claimed that Kastner was just a symbol of the dirty collaboration between Zionists and Nazis. Like the Revisionists, the Communists had their own political reasons for picking a fight with the ruling party.

The religious parties viewed Kastner as an emblem of the moral corruption at the heart of secular Zionism, even though the Nazi-appointed Jewish Commissions, or Judenrat, had contained plenty of religious Jews. And, of course, the religious had plenty of reasons to distrust the ruling party. Chief among them was Ben Gurion’s emphatic desire that Israel be a secular state, with civil laws that were not based on religion.

I know this happened 70 years ago, but wow, this was a REALLY BIG DEAL. Within the government, chaos reigned.

In the aftermath of the Kastner trial, the Israeli government seemed determined to rip itself apart.

We need to appeal the verdict, maintained members of Mapai.

We need to try Kastner under the Nazi Collaborators Law!, argued the Communist party, Maki.

Shut up and accept the verdict, gloated Herut. (OK, maybe not in those exact words… but I’m not exaggerating when I say that much saltier words were lobbied in the Knesset that day.)

Herut and the Communists (great band name by the way) submitted motions of no confidence in the government – meaning, basically, that they thought the government was too incompetent to make the correct decision regarding the aftermath of the Kastner trial. And in a huge upset, the General Zionist party, which were part of the ruling coalition, abstained from the vote.

Meaning that the government dissolved.

Meaning it was time for elections.

Election season was ugly. You can imagine the name-calling. The comparison of Mapai politicians to Nazis. The grandstanding. The savagery in the press.

And in the end, Mapai lost five seats.

Herut gained seven.

Moshe Sharrett resigned, and Ben Gurion took over as Prime Minister. He shied away from all mention of the politically toxic Kastner Trial, refusing to clear Kastner’s name.

And amid all this upheaval – not to mention the 1956 Suez Crisis! – Israel’s Attorney General appealed the verdict.

Though it would be two long years until the Supreme Court overturned HaLevy’s ruling, Kastner’s name was eventually cleared. Mostly. Four of five judges ruled that Kastner had not collaborated with the Nazis. All five judges ruled that he had certainly not laid the groundwork for the murder of Hungarian Jewy. There was nothing to do about the charge that Kastner had testified in favor of a war criminal, though. The signed affidavit was damning, and that ruling stuck.

Unlike Halevy, the Supreme Court’s opinion took into account the complexity of Kastner’s situation. Judge Silberg summarized this difficulty most poignantly: “A most difficult task has been imposed upon us in this appeal—to scrutinize deeds and occurrences which seem to have happened on a different planet, and to pronounce judgment on the behavior of men, hovering in the claws of Satan himself…. Are we capable—as fallible human beings—of sitting in judgment on the moral or immoral actions done by Kastner?”

But Kastner wasn’t around to enjoy his vindication. In 1957, he was assassinated by three veterans of Lehi – the super right-wing paramilitary that had split from the Irgun in 1940 to continue waging its war against the British.

In one of those delightful quirks of history, Kastner’s granddaughter, Meirav i, is currently Israel’s Minister of Transport. She’s on the Israeli left, involved in social justice movements, non-religious, anti-religious perhaps, and very open about her family’s past. Here she is talking about her family’s controversial history, and the role it played in shaping her life.

Meanwhile, her grandfather saved the prolific and influential anti-Zionist Satmar Rebbe, whose followers – the Satmar Hasidim – celebrate 21 Kislev as a holiday, commemorating the day their rebbe was saved from the Cluj ghetto by getting on the Kastner train. It’s hard to think about two people less alike than Merav i and anyone in the Satmar dynasty. Yet neither of them would be here today if not for Rudolf Kastner… though R’ Yoel Teitelbaum, the Satmar Rebbe, was so staunch an anti-Zionist that he refused to even testify at the trial.

So that’s the story of the Kastner trial, and here are your five fast facts.

- The Kastner trial started as a fairly open-and-shut libel case: an elderly Hungarian Jew named Malchiel Gruenwald accused Israel Rudolf Kastner – the spokesman for the Ministry of Commerce and Industry – of being a Nazi collaborator. As Jews go, Kastner had been a VIP in Nazi-occupied Hungary, and he had used what influence he had to negotiate with the Nazis, eventually saving 1,685 Jews from certain death. Among them were several members of his family and a number of prominent Jews, including Satmar Rebbe Yoel Teitelbaum. Somewhat ironically, the Satmar Hasidim are STAUNCH anti-Zionists.

- The Attorney General, Chaim Cohen, was enraged by Gruenwald’s accusations, believing that an attack on a government representative was an attack on the government itself. He insisted on suing Gruenwald for libel. But he didn’t bargain for Gruenwald’s defense lawyer, Shmuel Tamir. Like Gruenwald, Tamir was a fierce Revisionist Zionist. For him, Gruenwald was an afterthought. Far more important was taking down the Labor Zionists.

- In a brutal trial, Tamir took Kastner’s story apart, and by the end, Judge HaLevy’s verdict proclaimed that Kastner was guilty and had “sold his soul to the devil.”

- The trial caused a huge uproar across Israel. The press went wild, the Sharett government fell apart, and Ben Gurion came out of retirement to act as PM again. Mapai lost five seats in the next election – along with a LOT of its power. Meanwhile, Herut gained 7 seats, along with increasing prestige. Once again, Labor and Revisionists sparred from across the aisle, accusing each other of hideous things.

- Kastner’s conviction was appealed and overturned by the Israeli Supreme Court in 1958. But he was unable to enjoy his public vindication – he was assassinated by three gunmen who had served in the Lehi. This was Israel’s first political assassination, but it wouldn’t be its last.

Those are your five fast facts, but here’s one enduring lesson as I see it. Supreme Court Justice Moshe Silberg wrote about the trials of collaborators that “it is hard for us, the judges of Israel, to free ourselves of the feeling that, in punishing a worm of this sort, we are diminishing, even if by only a trace, the abysmal guilt of the Nazis themselves.” By “a worm of this sort” he meant someone who was a bit zealous in their collaboration with the Nazis. Someone whose small taste of power turned them cruel.

And I agree with Silberg. The blame lies with the Nazis and only with the Nazis. Let’s pause and remember that. Not with desperate, cornered people who made “choices” – such as they were – in an atmosphere of unimaginable trauma.

You may be familiar with the book or the film “Sophie’s Choice.” The title has become a shorthand for an incredibly difficult, impossible, painful decision. In the book and movie, Sophie’s choice is between her children. She saves her son, believing he is more likely to stay alive in the hell of Auschwitz. But her son’s life comes at the cost of her daughter’s.

Sophie’s Choice is fiction. But the calculus Sophie is forced into? The shattering decisions?

Those were heartbreakingly real.

I’m not a huge numbers guy – I like narratives over statistics – but I can’t deny the shocking power of the following fraction: two out of three European Jews were murdered in the Holocaust. Two out of three. I have three beautiful children… and my train of thought has to end there. It’s too ghoulish to keep thinking about, but if we are asked to remember the Holocaust, we must know what remembering the Holocaust actually means.

And that’s just – “just” – the people who were killed.

That’s the context in which Kastner is operating. To judge him for anything would be to exonerate – even if only in the tiniest increments – the Nazi machine.

But there’s a snag in this neat moral binary.

In The Saved and the Drowned, Auschwitz survivor Primo Levi wrote about “the gray zone” – the uneasy moral space where the collaborator and cooperator reside. It’s an ugly idea, hinting at complicity. But Auschwitz was an ugly place. Levi wrote that he “expected to find a terrible but decipherable world…. Instead… The world into one was precipitated was terrible, yes, but also indecipherable: it did not conform to any model, the enemy was all around but also inside.”

He doesn’t ask the reader to judge, by the way. But to even acknowledge that this gray zone exists is upsetting. And against this schema, the Kastner trial takes on new dimensions. Because we can say, without judgment, that Kastner is in the gray zone.

I started off this podcast talking about the concept of moral dilemmas, but the truth is that Kastner was not involved in any moral dilemma. He was involved in what is referred to as a “zero-infinity dilemma:” one in which “probabilities are tiny and consequences enormous…. In such cases calculation is only a caricature of rationality.”

Kastner was placed in an impossible position. To try and quantify what he did or didn’t do – to map it somehow using a “moral compass” – is beyond human logic and it should remind each and every one of us of the clear moral stance we learn in the Ethics of our fathers, “Al Tadin et chavercha ad she’tagia limkomo,” Do not judge your friend unless you’ve been in their situation.” Or, in the words of American historian Lucy Davidowicz: “questions about the Jewish opportunities and resources to halt the Final Solution appear absurd.”

So let’s leave aside absurdities and impossible questions and what-ifs and turn back to something that I’m certain of. To me, the biggest lesson of the Kastner trial is that the Jewish people do not have the luxury of internal squabbles. When the Jewish people do that, they win. We lose. The Nazis tried very hard to destroy us. We cannot – must not – give them or any of our enemies the satisfaction of destroying ourselves from the inside.

So I look back at Tamir’s fiery rhetoric, Halevy’s verdict, Gruenwald’s accusations, and I get sad. And perhaps above all, I think that the treatment of Holocaust survivors in the early days of the state was devastating. Because the Kastner trial was far more than a libel case. It was a trial of survivors, during which newly-minted Israelis tried hard to rewrite a history of Jewish suffering into a fantasy of Jewish resistance. In the words of survivor Avraham Harshalom: “People flying with me in the air force [in Israel], when they heard that I had been in Auschwitz, they would say things like ‘why didn’t you fight back’ or ‘if you survived then you must have been collaborating with the Germans.’ There really was no way of talking about it.”

Because if you’re a Jew in the early days of Israel, relishing the unlikely victory of having a state at last, it’s easy to invent an alternate history in which you would have fought back. You would have resisted. You wouldn’t have been powerless, going to your death placidly. And you wouldn’t have sullied your hands by negotiating with Amalek himself. Like I said, Al Tadin et chavercha ad she’tagia limkomo. Do not judge your friend until you’re in their situation.

And for their part, Holocaust survivors learned to lock away the trauma. To look forward, rather than back. Never to speak of what they had seen. What they had lost. What they had done. What had been done to them. But the Kastner trial came before Eichmann, in an atmosphere of denial and silence. So it’s no wonder that Kastner didn’t want a trial. Not because he was trying to hide, or not only because of that. But because it was too painful to remember. And it was taboo to remember publicly and remain unashamed.

So I think Kastner is too complicated to fit into a definitive category like “wrong” or “right.” I think his pain is too big. The weight of his choices too heavy. Too impossible for me to consider, let alone judge.

And I think, finally, that the decision – who to save, how to save them, what to bargain with, what makes the fairest exchange – is too big to be placed on a single person’s shoulders. This is why we have a state. So that no one person has to carry this burden alone. So that no one person has to carry it ever again.

Bibliography

- Tom Segev. The Seventh Million.

- Ben Hecht. Perfidy.

- Leora Bilsky (2001). Judging Evil in the Trial of Kastner. Law and History Review, 19(1), 117–160. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/744213

- Hanna Yablonka and Moshe Tlamim (2003). The Development of Holocaust Consciousness in Israel: The Nuremberg, Kapos, Kastner, and Eichmann Trials. Israel Studies, 8(3), Israel and the Holocaust, 1-24. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/30245616

- Yechiam Weitz (1996). The Holocaust on Trial: The Impact of the Kasztner and Eichmann Trials on Israeli Society. Israel Studies, 1(2), 1-26.

- David Luban (2001). A Man Lost in the Gray Zone. Law and History Review, 19(1). 161-17.

- “Joel Brand, 58, Hungarian Jew in Eichmann’s Truck Deal, Dies.” The New York Times, The New York Times, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1964/07/15/97339949.html?pageNumber=35.

- Laor, Dan. “Israel Kastner vs. Hannah Szenes: Who Was Really the Hero during the Holocaust?” Haaretz.com, Haaretz, 9 Nov. 2013, https://www.haaretz.com/.premium-who-was-the-real-holocaust-hero-1.5287614.

- Pnina Lahav (2001). A “Jewish State… to Be Known as the State of Israel”: Notes on Israeli Legal Historiography. Law and History Review, 19(2), 387–433. doi:10.2307/744134

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “Rudolf (Rezso) Kastner.” Holocaust Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/rudolf-rezsoe-kasztner. Accessed on March 20,2022.

- Hannah Szenes. “A Walk to Caesarea (Eli, Eli).” Perf. Ofra Haza. YouTube. November 26, 2020. Web. Accessed on March 20, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0jMQq0jYzbw&ab_channel=AntonioSalbertrand

- Yad Vashem: https://www.yadvashem.org/odot_pdf/microsoft%20word%20-%205978.pdf

- Israeli Govt: https://www.mfa.gov.il/mfa/mfa-archive/1950-1959/pages/nazis%20and%20nazi%20collaborators%20-punishment-%20law-%20571.aspx

- Asher Maoz (2000). Historical Adjudication: Courts of Law, Commissions of Inquiry, and “Historical Truth.” Law and History Review (18)3. URL: https://archive.ph/W2cAj#selection-471.1-426.8

- USHMM: https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/gallery/jewish-population-of-europe

- Times of Israel: https://www.timesofisrael.com/israel-says-worlds-jewry-still-2-million-shy-of-1939-numbers/

- https://www.haaretz.com/jewish/holocaust-remembrance-day/the-holocaust-facts-and-figures-1.5298803?lts=1647822682931

- https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,864174,00.html

- https://www.commentary.org/articles/w-laqueur/the-kastner-caseaftermath-of-the-catastrophe/

- https://m.knesset.gov.il/EN/About/Lexicon/Pages/NoConfidence.aspx

- https://main.knesset.gov.il/EN/About/History/Pages/KnessetHistory.aspx?kns=2

- https://www.mfa.gov.il/mfa/mfa-archive/1950-1959/pages/nazis%20and%20nazi%20collaborators%20-punishment-%20law-%20571.aspx

- Primo Levi, The Drowned and the Saved

- Lucy Davidowicz, The War Against the Jews

- https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/jewish-uprisings-in-ghettos-and-camps-1941-44#:~:text=Resistance%20in%20Ghettos&text=Their%20main%20goals%20were%20to,escaping%20to%20join%20the%20partisans.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tB4pU6JKsfQ&list=PLVV0r6CmEsFw4EQRLZvAoreWVLWLJDNaI&index=95&ab_channel=WebofStories-LifeStoriesofRemarkablePeople

- https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-quot-blood-for-goods-quot-deal-april-1944