Schwab: Welcome to Jewish History Nerds, where we do exactly what it sounds like, nerd out on awesome stories in Jewish history.

Yael: I’m Yael Steiner, and my childhood dream was to stay in school forever.

Schwab: I’m Jonathan Schwab, and I am in school forever. Yael, what story do you have for us today?

Yael: The story that I’m going to share today is profoundly sad.

Schwab: Okay.

Yael: But I have to say I enjoyed preparing for it so much. It’s a really interesting, thought-provoking, philosophical soap opera.

Schwab: Hm.

Yael: And while the result is not one that’s particularly happy for the Jewish people, it is just a treasure trove for history nerds.

Schwab: I feel like this could be anything.

Yael: (laughs) John Stewart had a line once when he was hosting the Oscars, and Steven Spielberg was nominated for Munich. And he goes, “Schindler’s List, Munich, I can’t wait to see what happens to us next.”

Schwab: Oh, gosh.

Yael: (laughs) He’s like, “Trilogy.”

Schwab: Oh, man.

Yael: So I’m obviously making light of the fact that unfortunately there have been many tragedies in Jewish history. And the story of Edgardo Mortara, who is the man we’re going to be talking about, is one of them.

Schwab: That’s not a name I’m familiar with.

Yael: It wasn’t a name that I was familiar with either. And once I’d done the research, I was fairly shocked that this was not something that had come up ever in my Jewish education. It’s fairly modern. Edgardo Mortara was born in 1851-

Schwab: That is fairly modern, yeah.

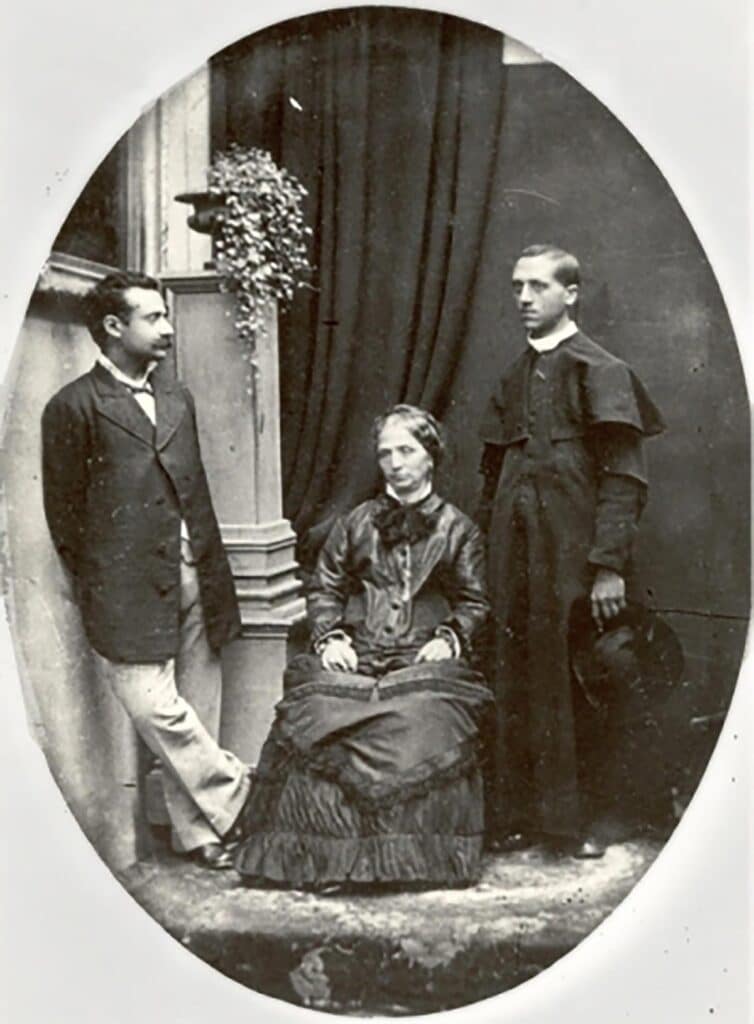

Yael: We have photographs of these people. And over 20 stories ran about this incident in the New York Times. So we’re really talking about modernity here. But when we get into the nitty gritty of what actually happened, you’ll think, “Are we back in medieval ruling eras?”

Schwab: And you said you were shocked that it hadn’t come up before. So it’s not like this story has been suppressed in some way. It’s just, it’s not a part of the series of stories we tell.

Yael: Not at all suppressed, though the Catholic Church doesn’t love talking about it.

Schwab: Of course they’re involved. Sure.

Yael: But the authoritative book on this incident came out in 1997.

Schwab: So who is Edgar Mortara and, and what happened? And what did the Catholic Church do this time?

Yael: So Edgardo Mortara was six years old in 1858. If he’s like any typical six-year-old, he probably would want me to tell you that he was almost seven in June of 1858.

Schwab: I know a couple six-year-olds who are almost seven, and like those, he was probably a huge fan of this podcast. (laughs)

Yael: And he grew up in a middle-class home in Bologna, Italy.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: And one thing to note going forward is that at that time, Italy was divvied up into a variety of kingdoms. There were some independent states. There were other independent states that were not aligned with the first group that I mentioned. And there was an area that was ruled governmentally by the Vatican, called the Papal States.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: And Bologna was part of the Papal States where the Pope essentially functioned as king as well as pontiff.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: And this is all happening in the very few years that lead up to the unification of Italy, which I think is called the Risorgimento or something like that. And that’s something to keep in mind, because the pope’s knowledge that his power was waning and likely on very shaky ground probably has a lot to do with his response to this particular incident.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: So Edgardo Mortara, six years old, summer 1858, he was one of eight children. His father and brother are not home. And one evening there was a knock at the door. And the papal police, essentially, in Bologna, said that they were there to take Edgardo away.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. On what grounds?

Yael: The rationale they gave for taking Edgardo away was that, A, it was by the order of the pope. But it was by the order of the pope because Edgardo had previously been baptized. And as a baptized person, he had to be raised as a Catholic in a Catholic environment.

Schwab: Hm.

Yael: So how did he wind up being baptized? What’s the-

Yael: So there are two things there. One is how did he get baptized. And then the second thing is the lawyer in me whose thoughts were borne out in the book The Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara, by David Kertzer, who is the preeminent scholar of this particular incident, is, it’s one thing for them to come in and say, “We’re taking your child because he’s been baptized.” But first, let’s actually answer the question, was he really baptized.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Schwab: Can I ask a question before you even get to that question?

Yael: Of course.

Schwab: Is this an isolated incident, or is this a thing where the papal police are going around house to house, and saying, “One of your kids was baptized. We’re taking them away now and raising them as Catholics like they’re supposed to be.”

Yael: It was not unheard of.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: Several hundred years earlier, I don’t want to say it happened frequently, but it happened slightly more frequently. By the 19th century, it really didn’t happen. The church had adopted a policy very expressly saying that they would not be baptizing children against the will of their parents because-

Schwab: Sounds like a good policy, yeah.

Yael: They recognized parental authority over their children. So it wasn’t happening in the 19th century. But that doesn’t mean that they acknowledge that anyone who had otherwise been baptized shouldn’t be raised a Catholic.

Schwab: You shouldn’t be forcibly baptizing people, but once it happens-

Yael: Exactly.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: So the rumor is that when Edgardo was an infant, he had been extremely, extremely ill. And the domestic worker who lived in the Mortaras’ home, a Catholic woman named Anna Morisi, who was young and unmarried, and that will come into play a little bit later on. Anna Morisi, out of very good intentions and fondness for the Mortara family, upon seeing that his family was praying, she secretly sprinkled water on him and said the baptismal prayers, because she believed that he was on the brink of death, and she wanted him to be able to go to Heaven. And Catholics believe that anyone who’s not baptized obviously cannot go on to the world to come, or the positive aspect of the world to come.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: So her intentions, very good.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: We have absolutely no reason to believe that she was antisemitic.

Schwab: Right.

Yael: We have no reason to believe that she wished harm upon the Mortara family.

Schwab: And that’s very different than, I don’t know, like an organized, surreptitious campaign to baptize lots of children. Like, that’s a person who’s clearly meaning well and… Yeah.

Yael: Yeah, she loved this child. She loved this family. And so she did what she thought was the best thing for his immortal soul.

The Mortaras really liked her, and she liked them. They had taken her in as an employee. She was a single woman who, ultimately, while she’s working for the Mortaras, is impregnated. They send her away to a foundling hospital where they pay for her care. And after her child is born and then I assume put up for adoption, she came back to work for them. And they paid her wages. And there’s no reason to believe there was any bad blood between these two sides of this equation.

Schwab: That baby’s not coming back into the story, right? Like, that was like, that’s like a-

Yael: No, it’s not. It’s not.

Schwab: I was like that’s either like, an irrelevant tangent or, or we’re gonna find out in Act 3 that like, that baby is the pope.

Yael: They get married. That’s Edgardo’s wife.

Schwab: (laughs)

Yael: No. They don’t. That baby does not come back into the equation.

Schwab: Okay.

Yael: But it should also be known that Anna Morisi did not share the fact that she baptized the child with the Mortaras, because obviously she knew that that’s something they would not approve of. And it would anger them. But she did it in what she said were, she thought were the child’s final moments.

Schwab: And she does though share that with somebody else I’m assuming.

Yael: That’s the question.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: So thankfully, Edgardo recovers. He grows into a healthy, bright, six-year-old boy. And at some point in the few months, proceeding his taking, it is brought to the attention of people in the village that Anna Morisi had done this. The prevailing theory is that she had mentioned it to a friend, the friend mentioned it to the parish priest, the parish priest mentioned it to the inquisitor in Bologna at that time because the Inquisition was actually still going on in Bologna at that time, as it was in other places in that area of the world. And the inquisitor sent word to Rome asking what to do. And the order came down, “We need to take this child and raise him ourselves as a Catholic.”

Later on, when the Mortaras are trying to disprove that the child had ever been baptized, as one legal route towards getting him back, they bring testimony from various villagers saying that it’s not true, this whole story is made up. Anna Morisi’s testimony that she learned the baptismal prayer from one of the grocers in town is refuted. The grocer says, “I don’t know what you’re talking about. She never spoke to me about this boy. “I never taught her the baptismal prayer.” I don’t know if that was true or not true. But the villagers really supported the Mortara family in this, to the extent that when they tried to discredit Anna Morisi’s character down the line to say she’s not a reliable narrator, one man comes forward. Well, basically they-

Yael: So there are a lot of rumors that are-

Schwab: So, so curious what he says. (laughs)

Yael: There are so, a lot of rumors that are circulated that she is a loose woman, which I guess is borne out by the fact that she had previously had this child.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: And this one man testifies that she could not have baptized the child, because at the time that she was alleged to have done this, he was watching her have relations with a soldier through a peephole in the wall.

Schwab: (laughs) Testifying about observing people having relations seems to come up far more often in these podcasts than I ever thought it would.

Yael: Guys, that’s not the kind of people we are.

Schwab: (laughs)

Yael: But this guy was willing to take one for the team and out himself as a creeper in order to help the Mortara family potentially get back their son. But I’ve gone way ahead into their legal strategy at trying to get their son back, First let’s talk-

Schwab: So I gather by context that he does get taken away and they work very hard to try to get him back.

Yael: Yes. So let’s go back to that evening. Obviously, his mother is distraught. She’s like, “What are you talking about?” She’s clinging to the child. The father and brother come home. They also don’t know what to do. Someone goes out to get a rich uncle type. He seemed to have connections in the town. And this uncle of Mrs. Mortara was able to get a 24-hour stay from the police to let the child stay with the family for 24 hours. During those 24 hours, the home was heavily guarded because there was a fear that the parents would try to sneak the child away, or even, to the Catholic mind, sacrifice him, rather than letting him be taken as a Catholic.

It should be noted that the police officers who came to the home, as well as even the inquisitor who goes on trial a lot later on for activities having to do with this story were not happy to be carrying out these orders.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: There’s testimony both from the police officers and from those observing the situation that the police officers did not want to be tearing this child out of his parents’ arms, that some of them seemed very hesitant or even teary-eyed at carrying out this particular mission.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Interesting.

Yael: So ultimately at the end of the day, many of the people involved here who do things that are detrimental to Edgardo and the Mortara family come off as very human and don’t come off as malevolent. But it’s, you know, “I was just following orders-” quote unquote. And you have to remember that at that time, the pope was the pope king.

Schwab: Yeah, like, it’s not just a religious instruction but it’s, it’s also a state function. Like, it’s political and religious and in charge of the police.

Yael: So ultimately, they managed to get Mrs. Mortara out of the house somehow by encouraging her to be comforted by friends. And after the 24-hour stay expired and appealing to the Catholic hierarchy in the city did not work, Mr. Mortara was, you know, holding the boy, sort of bringing him out to the carriage to be taken, with the strong belief that this whole thing would be rectified shortly and that there’s no way that the powers that be were going to tear a child from his parents’ arms for this reason.

And basically appealing to the Catholic hierarchy in the city doesn’t work. The Jewish community tries to appeal to the Rothschilds, who were providing capital to the Vatican at that time.

Schwab: I’m given to understand that they can make anything in the world happen, so I’m surprised to hear that that wasn’t successful.

Yael: It’s really interesting, because that is sort of an accusation that’s levied today and has zero truth to it. I don’t even think any members of the Rothschild family are still Jewish or identify as Jewish. But at that time, there were Rothschild banks that were providing capital to the Vatican. And even they were not able to prevail upon the administration to get involved here. What ends up happening is that a brother-in-law of one of the Rothschilds is Sir Moses Montefiore. I don’t know if you’re familiar with that name.

Schwab: He’s a builder of windmills in Israel, I’m pretty sure. (laughs)

Yael: Yes. There is a beautiful neighborhood in Jerusalem named after him, Yemin Moshe.

Schwab: And there’s a windmill there. (laughs) I don’t think he built it, but In my mind, they’re very associated.

Yael: Yes, he’s highly asso-

Schwab: He’s the rich windmill guy.

Yael: He’s the hospital in the Bronx guy.

Schwab: Yeah, I’m very familiar with that as well.

Yael: He is the chair of the Board of Deputies of British Jews, which is an important title.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: Jews in Britain are starting to really become part of the higher echelons of society. A Jew had just become a member of Parliament for the first time.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: And Moses Montefiore had just successfully returned from a voyage to the Middle East, where he tried to disprove a blood libel. He was a swashbuckling fixer in the Jewish world at that time. And he tried to intervene. He traveled to Rome to try to get an audience with the pope.

Schwab: Wow.

Yael: He never gets to the pope. He kind of gets to the second in command. And the word that comes down from the pope via the second in command is, “We understand your sadness, your dissatisfaction with the situation, but-“

Schwab: Mm-hmm, but, like, the law is the law and-

Yael: The law is the law. And this is a Catholic boy, and he needs to be raised as a Catholic. And to let him be raised in a Jewish home would put him in a state of apostasy. So in the interim, Edgardo had been taken to a school in Rome that was particularly for Jews who were becoming Catholics.

Schwab: Sure.

Yael: The pope actually financially supported it-

Schwab: Of course.

Yael: … for the rest of his life and endowed a trust for him.

Schwab: Mm.

Yael: Edgardo was taken to this school where he excelled. It happens to be that this person turned out to be a prodigy, that the one boy who got ensnared in this whole situation ended up speaking at least six languages, including the Basque language, which is apparently exceedingly difficult to learn.

Though some in the Catholic community say that this was all part of the plan is that of course this boy is a prodigy, because this is a boy who was chosen to be a Catholic and was always meant to be a Catholic.

Schwab: Hm, but not the baptism made him prodigious.

Yael: No, no, no. When Moses Montefiore gets nowhere with the pope. He brings this to the attention to the American Jewish community. And there are rallies and protests all over the United States. 3,000 people gather in San Francisco, of all places. I mentioned I think the 20 articles, maybe even 30 articles, in the New York Times about this. Uh, the Baltimore paper, the Milwaukee paper-

Schwab: Wow.

Yael: … um, I believe the Boston paper all covered this.

Schwab: Hm.

Yael: It became a huge cause célèbre. I think that’s how you pronounce that.

Schwab: (laughs) I have no idea how to pronounce it. That is a thing I’ve definitely only ever seen written.

It sounds like, in our childhood there was a story about a young boy from Cuba who-

Yael: Elian Gonzalez.

Schwab: This young boy who is separated from his family, and there’s a public swelling of support behind saying, this child belongs with his family.

Yael: Right.

Schwab: I don’t remember exactly what it was. He was separated from his family and… Yeah.

Yael: And they just were not swayed by the appeals that he’s a child, he’s not at fault, he should get to stay with his family.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: But a hundred percent there are so many parallels here.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: I did write about him in my notebook that I’m holding in my hand.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: Rabbi Wise of Cincinnati, one of the founders of Reform Judaism, wrote an extremely, extremely anti-Catholic op-ed in one of the papers, where he casts the pope as the prince of darkness.

Schwab: Oh.

Yael: And obviously, that’s an extremely Voldemortian descriptor. But one of the reasons he’s able to get away with it is that anti-Catholic sentiment in the US is very high at this point in time. Um, a lot of Italian immigrants coming in and Irish immigrants. And I guess the xenophobic element took shape as anti-Catholic sentiment. So it wasn’t as though the pope had a ton of support in the United States at this time.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: But interest really grew in the US. I think interest in the US about this outlasted interest in Europe.

Schwab: Yeah. It feels like it’s, it’s an easy narrative, for people to grab onto if, like… Well, that seems like a very dated definition of religion that, because this ritual was performed, therefore another religion gets to lay claim to this person’s identity. Like, that’s not really how we view things in a modern sense.

Yael: And anyone who’s a parent… And you don’t even have to be a parent. I’m not a parent.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: Anyone who has a loved one can sit back and say, how could you do this to a six-year-old boy?

Schwab: Right. Children should not be ripped from their homes because allegedly someone at some point performed some rite on them that no one asked for.

Yael: It’s a time in human history when people are starting to think about the doctrinal elements of their religions, and how they can square with life in the modern world, which is certainly something that we still deal with today.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: But they were dealing with it then in their own ways, um, when thinking about, the most devout Catholics, who might think that Edgardo would be relegated to Hell for not being baptized and for living as a Jew and still understand why there was cruelty in this, and still could have declined to participate in this particular mission.

Schwab: Yeah. Yeah.

Yael: Just to follow up on one thing about the US involvement, this was definitely communicated to President Buchanan in 1859. He declines to get involved for a variety of reasons.

Yael One of the main reasons why he didn’t get involved is because literally the country was a tinderbox. This is 1859. The Civil War is months away from starting. And he had his hands full. But in a related manner, he said, “How am I gonna get involved in the fate of this young boy who was stolen from his parents, when I have thousands, if not tens of thousands of children who are being stolen from their parents all the time on my soil as slaves?”

Schwab: Wow.

Yael: So that was his argument, that he wasn’t saying he thought any of it was right, but he does not get involved. All of the efforts fail. The money efforts, the press efforts, the personal pleas, the legal route, everything fails. Edgardo continues his learning. He continues to thrive in the schools that he’s educated in. By the time he’s 10, the pope is even sort of taking him out on display as this amazing Catholic prodigy child.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: And I guess, Edgardo at that point, loved his life.

Schwab: Right, like, embraces this, I assume. Like, doesn’t know anything different or doesn’t remember, yeah.

Yael: Right, Edgardo learns to love his surroundings-

Schwab: But, they have a lot riding on it also. LikeThere are a lot of things you can do to make children happy, and I assume they very much wanted him to be happy, you know.

Yael: Yes. Yes, absolutely. They weren’t taking him to keep him in a dungeon. They were taking him and trying to give him the best Catholic life they could. They just were paying no heed to the fact that they had done this terrible thing to, both to the child and to his family.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: His family did have visitation rights, limited visitation rights.

Schwab: Oh, I see.

Yael: He was able to see them a few times over the years. It really pained them to see how much he had acclimated to life in the church. He really was being treated as a son by the pope almost.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: There’s some written evidence that the pope writes something about he understands that this child was taken from his biological parents, but he goes, “But I am also his father.”

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Of course. And I’m dreading asking this question, because I feel like you were clear that it’s a sad story. But, like, how does his adult life unfold, you know, and like, where does he wind up?

Yael: So by the time he’s 19, he is well known as a preacher.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: He basically takes it upon himself to proselytize to other Jews all over the world about why they should become Catholic. When he’s 19 in 1870, the Papal States completely fall. Italy is unified. And someone gets it into Edgaro’s head, that he’s emancipated basically, and he can leave Italy if he wants to. And I think his life had gotten so challenging there, just because he was this public figure in a way that he probably never wanted to be. He flees to Belgium. And that’s where he spends most of the rest of his life as a home base. But he travels around the world preaching.

Around the time that Italy is unified, he’s preaching in France. And his mother and brother come to see him. I’ve left out of this story the fact that, during the decline of the Papal States, the pope was heavily reliant on the French for defense. And Napoleon the Third had actually intervened with the pope and said, “If you do this, our diplomatic relations are over.”

Schwab: Wow.

Yael: So it really, really hastened the fall of the Papal States. And Edgardo’s brother ends up joining the French forces I think partially because of that. And that’s the way that he’s able to bring his mother to go hear Edgardo speak.

And from that time on, they maintained regular contact. But it was never anything beyond him respecting his mother because the bible tells us to respect our parents.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: And I do think he loved her. But he never once contemplated going back. In fact, his path was that he was constantly trying to convince the remainder of his family to convert to Catholicism so that they could all be together. And in fact, that was one of the options that was presented to the Mortaras early in this saga was, “If you guys all convert-“

Schwab: Right, then you can continue living all-

Yael: “… then you can spend… It’s all good.” Honestly, there are parents who would make that decision in a heartbeat. And that’s why this story is so complicated. And I don’t think we’re gonna have time to talk about this, but in a similar vein, there are so many children who were hidden in the Holocaust by wonderful, wonderful Catholic families.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: A lot of them are not returned to their Jewish families. A lot of them don’t have families to return to.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: But a lot of them aren’t returned and grow up as good, happy Catholics. People are in their 80s, 90s, finding ou for the first time that they were Jews.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. I feel like I grew up hearing the stories of, the kids who are returned to their families when they’re, you know, 12 or 13, because then they spend the rest of their lives as Jews, and like, they’re the ones who speak in synagogue on Holocaust Remembrance Day, things like that.

Yael: Right. But the culture shock-

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: … that those children and adolescents went through… Imagine being hidden away at the age of three by a Catholic family during wartime, where they obviously never tell you that you were born a Jew, because how traumatic would that be?

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: Find out that your parents left you here, and then they were taken to a death camp. Those children find out at age 12 or 13. There’s actually a famous case in Italy, where there were two brothers whose parents were killed, and an aunt tried to get them back. She ends prevailing after a long time. But if you’re a good Catholic boy who’s grown up in Catholic school and then you go live with an aunt you’ve never met, who tells you you’re a Jew? It’s a very challenging situation all around, which is again why I talked a lot about intentions her, because this isn’t only about doctrine. This is also sometimes about the well-being of humans.

And if the Mortaras would have caved to that request that they all convert, what precedent does that set?

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: I don’t think anyone would have blamed them. So yes, Edgardo becomes a fairly well known preacher. He travels all over the world, He’s brought to the United States by a group of Catholics in Brooklyn, but that group of Catholics in Brooklyn ultimately asks him not to speak in New York, because relations between the Jewish community and the Catholic community in New York were just starting to get better.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Yeah.

Yael: They didn’t want to throw a firebomb into that. But he did preach all over the country. There were a lot of people who were very curious about him. He’s well received as a preacher by Catholics all over the world. He lives out the rest of his life in Belgium.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael : And he dies at the age of 80 in Belgium, just a few months before the Nazis invade Belgium when he would have been deported and most likely killed-

Schwab: The Nazis consider him Jew-, yeah. Like, What is Jewish identity, right, is, like, something that comes up all the time. That’s such a part of this story, because from the Catholic Church’s perspective, doesn’t matter how he was raised for the first couple years, doesn’t matter who his parents are, because he was baptized. He’s Catholic, not Jewish. And then the Nazis, also not Jews, who would say doesn’t matter how he lived his entire life, just based on his birth he is a Jew. Seems like everyone’s always asserting just whatever it is that is the worst thing for the Jews.

Yael: Exactly. We’re gonna choose the worst possible outcome.

Schwab: Yeah. I was surprised that you said that he died at the age of 80, because I thought you were gonna say, he dies very young and he lived this, like, brief, very sad life. But it sounds like he spent-

Yael: No.

Schwab: … 74 years as a Catholic.

Yael: He lived a long life, happy in the Catholic Church, after having spent his childhood as a very famous little boy.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: Pope Pius the 9th, who was the pope behind all of this was beatified and is in the beginning stages of becoming a saint-

Schwab: Mm-hmm. I know enough about Catholicism to know that’s some sort of process. Like, first you’re beatified. And then you can become a saint. And you have to have done miracles or something. I don’t know. That’s for Catholic history nerds. (laughs) Our sister podcast. (laughs)

Yael: The Catholic Church has never apologized for this incident.

Schwab: I was gonna ask that. like, has there been a reckoning and a realization?

Yael: None.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: None whatsoever, though David Kertzer, who I mentioned as the preeminent scholar of this does make clear, because that… The Jewish-Catholic relationship has changed tremendously since Vatican Two in the mid-’60s.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: So a lot of these things that we’re talking about have been rectified by the church in good faith, certainly by a lot of members of the church, not everybody, but we are in a totally different place now in our relationship with the Catholics. But even as much as that is true, there has never been an apology for this incident.

Schwab: Hm.

Yael: And there are plenty of people today who say the church shouldn’t apologize because they were just following canon law.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: And we don’t change the canon law for your feelings.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Yeah. I, I’m not arguing for it, but I do understand. Like, all religions have to grapple with things like this in some way of just like, well, according to the law, we shouldn’t be forcibly baptizing people, but once it happens-

Yael: What do you do?

Schwab: … like, according to our laws, this person is Catholic, and we cannot deprive them of, the education and, and the requirements that all Catholics have, so.

Yael: If you view the canon law as the will of God, same as if you view the Torah as the will of God, you cannot be persuaded to put it aside for contemporary sensibilities. And that’s what’s really hard in today’s day and age where we respect people’s religious beliefs and we respect diversity.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: But what happens when that respect yields a line crossing that is hurtful. And that’s why I think this is still so relevant to us today, not only. Because of this tragic thing that happened to a young Jewish boy in his family, but because we deal with these issues in our own Jewish lives every day.

Schwab: Yeah. But then there’s also a part of me, like, if you’re saying that we have to do this, aren’t there thousands of Catholic children probably who also should be given all of the resources and be getting an education and personal attention from the pope? And like, It seems like you’re very specially focusing on this one person. And like, if every single Catholic kid in Italy was getting that same, level of attention and resources, I would buy it a little more. But it kind of seems like, they’re in an element of, politics here and, like, deliberately doing something.

Yael: Right. Are you going into homes of Catholic families who are non-observant and taking their kids away?

Schwab: And, and making them all like, be forcibly educated in the same way.

Yael: Right.

Yael And there’s so much here. I could not recommend David Kertzer’s book more highly.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: Actually, one of the criticisms that he got for his book is that it must not be true because it reads like a novel.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: It’s so well written.

Schwab: The most interesting part of this story is that before an hour ago when we started, I had never heard of this. And I don’t understand how this isn’t something that we talk about more.

Yael: I know! It’s important. And I really mean this sincerely. I was thinking about this this morning. I’m so grateful that I have the opportunity to learn things like this because it’s so crazy to me that I had never heard of it before. It enhanced my gratitude that I have the opportunity to do this podcast with you and learn new things.