In the mid-17th century, Jews were reeling from the Chmielnitzki Chmielnicki Massacres, a bloody series of pogroms that devastated the Jewish communities of Eastern Europe. The barbarity of this tragedy, combined with the rise of a new form of mysticism called Lurianic Kabbalah, stirred hopes of a long-prophesied Messianic era. Lurianic Kabbalah, developed by Rabbi Isaac Luria in the mid 16h century, taught that a portion of G-d’s essence had fractured into many tiny sparks hidden in the material world.

He saw the scattering of the Jewish people as a divine plan to elevate the world’s hidden sparks through the performance of G-d’s commandments. Rabbi Luria taught that most of these sparks had already been redeemed, and that Israel would soon be restored. The stage was set for the coming of the Messiah.

Becoming a false Messiah

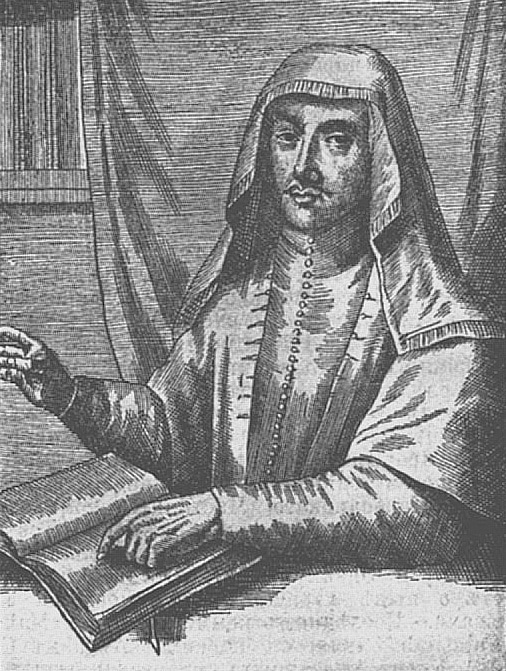

In 1648, a small band of Jews living in the Aegean coast of the Ottoman empire began to follow a young charismatic scholar and mystic named Shabbetai Tzvi. Known for his multi-day fasts, cold-water immersions , and elaborate expositions of mystical texts, Shabbetai Tzvi longed to receive revelations of mythic proportions. The local rabbis warily watched the 22-year old leader engage in strange practices like attempting to make the sun standstill at midday. He even publicly pronounced a name of G-d, which was only allowed to be said by the High Priest in the Temple of Jerusalem on the most sacred holiday, Yom Kippur. By 1651, Shabbetai’s antics grew more brazen, and the rabbis banished him from his hometown.

A wandering Jew

For 14 years, Shabbetai Tzvi wandered through the Ottoman empire. Jewish communities generally welcomed the handsome scholar, but inevitably, Shabbetai’s odd behavior, likely due to a combination of depression and mania, alarmed his new neighbors. When he landed in Thessaloniki in the mid 1650s, he invited the local Rabbis to his wedding – where he married a Torah scroll. Eventually he made his way to Constantinople, but was kicked out in 1658 when he celebrated three holidays in one whirlwind week.

By 1665, Shabbetai’s depression had become so debilitating that he sought a well-respected, mystical faith healer known as Nathan of Gaza. What was Nathan’s diagnosis? Instead of healing him, he proclaimed him to be the true Messiah! Shabbetai rejected the notion, but Nathan claimed to have prophetic powers, and persuaded Shabbetai to accept his role as Messiah and end the terrible exile.

Together, they gathered a group of believers and made a grand proclamation in Jerusalem. The rabbis quickly excommunicated him, but this time, his followers were too passionate to be squashed. Nathan wrote letters to Jews across the world describing how Shabbetai would depose the Ottoman Sultan who ruled Jerusalem and lead his people triumphantly back to the kingdom of Israel. The letters generated a messianic fever and Jews across the world packed their belongings — ready to travel to Jerusalem at a moment’s notice.

But the local Jewish leaders were torn. Some authorities, like Rabbi Jacob Sasportas, were sure Shabbetai was a fraud. Sasportas sent warning letters against the false Messiah to Jews around the globe. But, Shabbetai’s following was so impassioned that most opposition was suppressed by threats of violence.

The end of Shabbetai the Jew

In the Winter of 1666, Shabbetai sailed to Constantinople to play out Nathan’s vision and take the Ottoman throne. Turkish authorities caught wind of this plan, and arrested him upon arrival.

Instead of being killed or even tortured, bribes transformed his prison sentence into a regal stay at what became known as the “Tower of Strength.” Thousands flocked to his tower both to pay homage and to investigate his legitimacy. Rabbinic authority David ha-Layvee Seegal sent two emissaries to sniff Shabbetai out, but they couldn’t determine whether Shabbetai was a true or false Messiah. Finally, the mystic, Rabbi Nechemia ben Kohen, challenged Shabbetai to a three-day debate, determined he was a fraud, and convinced the Ottomans that Shabbetai’s ambitions for the throne would put their empire at risk.

The Sultan gave Shabbetai an ultimatum: convert to Islam or die. His followers awaited a miracle with bated breath. The next day, Shabbetai appeared in a turban, took a Muslim wife, and changed his name to Aziz Mehmet Effendi. He wrote that it was “G-d’s will” he become a Muslim.

Nathan of Gaza justified the conversion as a final plunge into the forbidden in order to elevate the last, hidden sparks of G-d. Nearly 300 families also converted, and became known as the Dönmeh, a sect of hidden Jews that continued into the 20th century.

Shabbetai Tzvi’s story became an embarrassing stain on the Jews. Most of his followers admitted their mistake, but for a long time, an underground following persisted. Rabbinic authorities toiled to weed out Shabbatean views from mainstream Judaism. Many Jews became jaded in the process, losing faith in themselves as well as the rabbis who had been blind to Shabbetai’s delusions. As Chaim Potahk summed up the events, “There had been numerous false Messiahs in Jewish history; none had so affected the total people […] as had the movement led by Nathan of Gaza and Shabbetai Tzvi”.