In the spring of 1991, my kindergarten class got a new classmate, Uri, who had just moved to Baltimore from Israel. And his show and tell blew the rest of ours right out of the water.

Twenty kindergarteners sat criss-cross applesauce on the A, B, C’s rug in the center of the room, watching wide-eyed as Uri and his mom presented a strange and menacing object. It was shiny and black, with huge reflective eyes and a protruding snout that ended in a sealed cap. Its straps dangled uselessly as Uri’s mom held this thing aloft and Uri explained, with a child’s heartbreaking matter-of-factness, that this was his gas mask.

Five-year-olds might not know words like “chemical warfare,” but Uri gave us a brief, developmentally-appropriate summary of the mask’s purpose, which in my memory – yes, I have a bizarre memory – went something like this: “The mask helped protect us when bad people wanted to hurt us. When we heard the sirens, we would go into our mamad with our masks on and sit there until it was time to come out again.”

I don’t fully remember how five-year-old Noam reacted to the gas mask, or to the idea that bad people wanted to hurt my new friend. I don’t remember asking why a gas mask existed, or how it helped keep the bad guys away. And I definitely didn’t know that mamad, or Merhav Mugan Dirati, referred to a room made of reinforced concrete, with a heavy metal door, where Israelis seek shelter from rockets and missiles. I didn’t know that Israeli law mandates that every house built after 1992 includes a mamad. I’d wager that, and I do not think I am exaggerating, as of 2022, there is not a single Israeli in the country that has not fled to a mamad at least once.

But 36-year-old Noam has seen the footage. Heard the speeches. Read the books, the articles. Tried to understand the geopolitical trainwreck that made five-year-olds all over Israel believe that gas masks and bomb shelters were just a normal part of life. And 36-year-old Noam remains incredibly thankful for the choices that the Israeli government made during that terrible time.

And that’s what we’re going to talk about today. The 1991 Gulf War, and its enduring geopolitical legacy. You might not have expected a war between Iraq and Kuwait to affect ordinary Israelis, test the US-Israel relationship, and even challenge the long-held Zionist ethos. And pay close to attention to that, because we’re coming back to it.

But that is exactly what happened. And that is exactly why this podcast exists: to unpack the numerous, sometimes complicated, always fascinating connections between seemingly random events. Because though it has since been eclipsed by its bloody sequel, the First Gulf War of 1991 was incredibly influential for the entire Middle East. And to understand the impact of Milhemet HaMifratz – as Israelis call the war – we have to rewind to 1979, when a certain Iraqi dictator tried his very best to upend the delicate balance of power in the Middle East…

The First Gulf War

Saddam Hussein had already enjoyed a long and bloody career by the time he officially became Iraq’s president, prime minister, and chairman of Iraq’s Revolutionary Command Council in 1979. Saddam’s rise to the top was littered with bodies. Because if you can’t force your people to love you, you do the next best thing: you make them fear you. And as a Sunni ruling a majority-Shia country, Saddam took this philosophy to heart, embarking on a systematic campaign to persecute and oppress the country’s Shia majority.

And his first move as head of state? Wresting the Persian Gulf from his Shia neighbor to the east.

Iraq and Iran had been sniping at each other for decades, and Saddam was hungry for a piece of Iran’s oil fields, natural gas reserves, and access to the Persian Gulf. But getting rich off stolen resources was merely step 1 of his plan to replace Egypt as the de-facto leader of the Arab world.

So Saddam was watching with great interest as the Iranian government crumbled and Islamic cleric Ayatollah Ruholla Khomeini turned the once-vibrant country into a repressive theocracy.

(Nerd corner alert: Before the Islamic Revolution in 1979, Israel and Iran enjoyed a warm relationship. Here’s a snippet from an Israeli documentary called Before the Revolution, about life in Iran pre-1979: “As Israelis in Tehran, we lived like millionaires.” And “The cooperation with Iran was tremendous…. “Iran bought a lot of weapons from Israel.” Really makes you think about what could have been…)

But Iran had bigger issues on its mind than Israel… like its grabby neighbor to the west. Seizing his chance to get his hands on Iranian resources, Saddam invaded in September of 1980, setting off a bloody, protracted war that would last eight years, cost $1 trillion, and claim between 1 and 2 million lives. By the time a ceasefire was declared in 1988, neither country’s border had moved an inch.

To finance his failed war, Saddam had borrowed billions from neighboring oil-rich states, like Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. But when tiny little Kuwait refused to cancel Saddam’s debt – which, yes, he had the chutzpah to demand – he did what all sane, rational folks do: threaten, insult, and eventually invade.

On August 2, 1990, Iraqi tanks rolled into Kuwait. And within a matter of days, Saddam had driven the royal family into exile in Saudi Arabia, installed a puppet government, and declared Kuwait a province of Iraq. Hundreds of thousands of people became refugees, and the ones who remained may have had it even worse. I’m not going to get too graphic here, but let’s just say that Saddam really earned his reputation as a violent monster. Not going to get into it all, but check out the show notes if you wanna learn more.

The world was horrified, and had no intention of letting Saddam continue to abuse Kuwait. And when I say “the world,” I am only sort of exaggerating. Because Saddam – who had previously enjoyed American and Saudi support during the Iran-Iraq war – was suddenly very unpopular internationally.

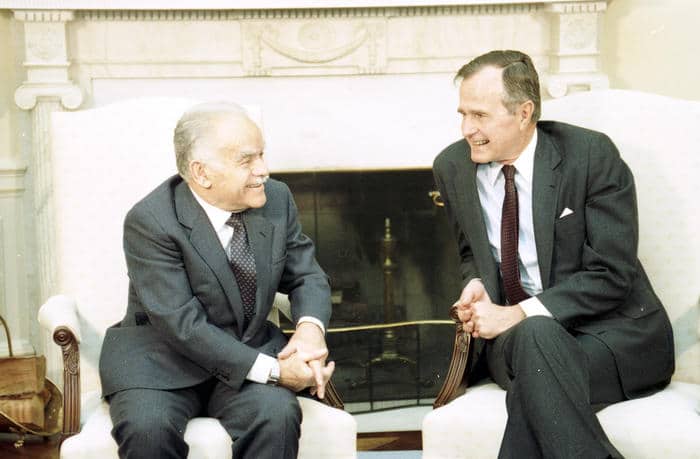

Here’s the first President Bush addressing Congress after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait:

“Our objectives in the Persian Gulf are clear, our goals defined and familiar: Iraq must withdraw from Kuwait completely, immediately, and without condition….This is not, as Saddam Hussein would have it, the United States against Iraq. It is Iraq against the world…. You know, I’ve just returned from a very productive meeting with Soviet President Gorbachev. And I am pleased that we are working together to build a new relationship. In Helsinki, our joint statement affirmed to the world our shared resolve to counter Iraq’s threat to peace.”

True, the US and USSR had met in tiny, beautiful Malta the year before to declare that the Cold War was finally over. (Nerd corner: Historians still debate whether that 1989 summit was actually the end of the Cold War.) Regardless: seeing the two nations working together was a pretty pretty pretty big deal for Americans who had spent decades afraid of their nuclear, Communist rival.

U.S. invasion

Unfortunately, even the world’s superpowers had little effect on Saddam’s expansionist ambitions. And despite Iraq’s ruined economy, six months’ worth of international sanctions and embargoes failed to rout Saddam’s forces from Kuwait. So the US – backed up by a whopping 34 countries – turned to Plan B: bombing the hell out of Iraq. Even Arab states who had once supported Saddam now agreed: the mustachioed maniac from Iraq could no longer be allowed to further destabilize the Middle East. Because if Saddam was allowed to continue running roughshod over his neighbors, Saudi Arabia would be next. And that would put Saddam in control of nearly half of the world’s oil.

To quote Saudi Arabia’s king verbatim: “hell, no.” Seriously, direct quote.

So as the US, Saudi Arabia, the UK, Egypt, and thirty other countries got together to give Saddam a little taste of his own medicine, Saddam did something a little unexpected… He threatened Israel.

Threats to Israel

Say what you will about Saddam Hussein, but when he committed to something, he went all in. So not a single person doubted that he’d make good on his threat to turn Israel into – and I quote – “a crematorium.” Lovely, Saddam. You really do have such a way with words.

For obvious reasons, Israel takes genocidal threats pretty seriously. And Saddam, unfortunately, already had a track record. He’d been systematically exterminating Iraq’s Kurdish population for years using both conventional and chemical weapons. And it was strongly suspected that he had some nasty bioweapons in his arsenal, like botulinum and anthrax. Honestly, I’m not 100% sure what either of those do to the human body, but I’m pretty sure it’s not good.

But why threaten Israel, which had nothing to do with this conflict? It had no oil. It hadn’t lent Saddam money. It had no relationship to Kuwait. It wasn’t even a part of the US-led coalition that had just attacked Iraq!

Well, as usual when it comes to Middle Eastern history, the answer is complicated.

Why Israel

First, let’s get the obvious motivation out of the way: good old-fashioned Jew hatred.

Antisemitism – both in its OG form and in its new disguise of anti-Zionism – were nothing new in Iraq. In 1941, pro-Fascist, anti-British forces overthrew the Iraqi government, cozied up to Axis powers, and effectively ended 2,600 years of vibrant Jewish life with the Farhud riot. (That’s our next episode — brace yourselves.) And then, Iraq refused to recognize Israel, sending troops to attack the Jewish state in 1948, 1967, and 1973. I’d imagine Iraqi leaders’ frustration only grew every time they lost a war against Israel. I admit it: I’m not above finding this extremely satisfying.

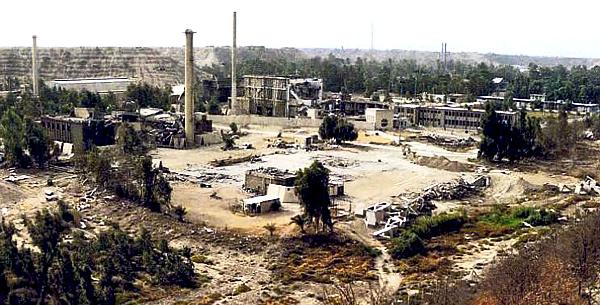

Next, we’ve got Saddam’s bruised pride. See, Israel had destroyed Iraq’s nuclear reactor at Osirak a decade earlier, back in 1981. And when you’re a brutal dictator with designs on ruling the entire Middle East, it’s gotta hurt when a Jewish country a twentieth of your size, the cute little nebbish Jewish people, just… destroys your one chance at nuclear domination.

Finally, Saddam had a third, and more immediate, reason for attacking Israel. As a pan-Arabist, he really hated that there were Arab states in the US-led coalition against him. So he thought maybe by bombing Israel, he could goad the country into joining the war. Once Israel did that, the Arab states in the coalition had two options – one far-fetched, and one highly likely.

- First, the pipe-dream option: Once Israel joined the war, the coalition’s Arab nations would switch sides and join Iraq, because they wouldn’t be caught dead fighting on the same side as Israel. (Side note: my nine-year-old is more mature than this.)

- And the far likelier option: the moment Israel joined the fight against Iraq, all the Arab states would be forced to pull out of the US-backed coalition. Just…stay on the sidelines. And since Saudi Arabia and Egypt were the second- and fourth-biggest backers of the coalition, their exit would be a huge coup for Saddam.

Even full-blown lunatics have an occasional moment of political savvy.

And just to add, this wasn’t the first time Saddam had invoked Israel during his invasion of Kuwait. In the words of Israeli historian Avi Shlaim: “It was Saddam Hussein himself who, ten days after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990, created the link [between Israel and Iraq] by suggesting that Iraq would withdraw from Kuwait if Israel withdrew from all occupied Arab territories. That was the mother of all linkages!”

Now, a guy who invades two of his neighbors, wipes out thousands of Kurdish villages with chemical bombs, and terrorizes his own people isn’t motivated by the kindness of his heart. So no one truly believes that Saddam invaded Kuwait to prove a point to the wider world and to win a home for the Palestinians. And to think he would have pulled out of Kuwait if Israel pulled out of the West Bank and Gaza is frankly laughable. As a 1991 Washington Post article puts it, “What began as an act of naked aggression toward Kuwait has been transformed into the culminant act of the drama of his life. Although he had previously shown little concern for the Palestinian people, the shrewdly manipulative Saddam wrapped himself and his rape of Kuwait in the Palestinian flag.”

Saddam and Arafat

Regardless of his motivations, Saddam became somewhat of a hero among Palestinians. And, crucially, to their leadership. Because guess who pointedly did not join the coalition against Saddam, essentially choosing instead to support him?

This podcast’s old frenemy, Yasser Arafat. Chairman of the PLO.

It might seem strange and unwise for Arafat and the PLO to back Saddam… especially because half of Kuwait’s 400,000 Palestinians fled the Iraqi invasion, terrified of persecution. And as we mentioned above, Saddam wasn’t really a warm and fuzzy guy.

But according to Palestinian-American historian Rashid Khalidi, the PLO “opposed the Iraq invasion of Kuwait but was unwilling to endorse a major United States military presence in the heart of the Arab world. …For the Palestinians, occupation and annexation of Kuwait is a great evil, but a massive American military presence in the region is an even greater evil.”

Kind of a “the-enemy-of-my-enemy-is-my-friend” sort of thing.

But what about the other Arab states of the coalition? Why was the PLO so willing to break with them?

Well, the Palestinians – justifiably, in my opinion – essentially felt left behind by their fellow Arabs. The rich Gulf states seemed more interested in cozying up to the West than advancing the Palestinian cause. Meanwhile, so-called moderate states like Egypt, who enjoyed a cold diplomatic relationship with Israel, had proved unable to promote the Palestinian cause or even change Israeli and American policy towards the PLO. So Arafat gambled that Saddam’s brash, take-no-prisoners approach would shock the Arab world out of its complacency and into supporting the Palestinian cause.

Because to the Palestinians, what did it matter if Saddam sincerely cared about the Palestinian people or if he was cynically using them as a political pawn? He seemed like the only person willing to confront the West. To actually act on his threats against Israel.

As we’ll see shortly, Arafat’s strategy backfired royally. And yet, much of the Palestinian community remembers Saddam fondly. Listen to some of the responses from this 2019 street poll, “What do you think of Saddam Hussein?”

So Palestinians weren’t too fussed about Saddam’s threat to attack Israel. But as Saddam’s bluster grew increasingly genocidal, Israelis grew understandably panicked. Through the end of 1990 and into 1991, the Israeli government distributed gas masks, just like the one Uri and his mom showed my class. And to go along with the masks, they also distributed auto-injectors filled with atropine, an antidote to certain types of nerve agents.

I want you to think about that for a second. Imagine putting your life on hold for an afternoon because you need to get a properly-fitted gas mask. Imagine having to explain to your kids, if you have them, that you might need to give them a shot so they don’t die from a chemical attack. Imagine how a nation full of Holocaust survivors felt as yet another mustachioed dictator threatened them with poison gas.

Saddam attacks Israel

Imagine hearing this announcement booming from your radio, as Israelis often did in the early weeks of 1991:

“This is not a false alarm. There has been a missile attack on Israel. All citizens of Israel must put on their gas masks and enter a sealed room. Check that your children have put their masks on correctly, and continue to listen to our instructions. This is not a false alarm.”

From the moment Saddam had invaded Kuwait in August of 1990, he had made himself at home. And as he plundered the country and blustered about his power, the United States and Saudi Arabia began quietly massing their troops. In fact, this was the American military’s largest overseas deployment since World War II. Because though the UN Security Council had given Saddam until January 15, 1991 to get the heck out of Kuwait or be forcibly removed, no one really expected him to listen.

Surprise, surprise, he blew past his deadline… and at 3 AM Iraqi time on January 17, 1991, the US-led coalition attacked the Iraqi air force.

In response, Saddam fired his first 8 Scud missiles at Tel Aviv. And by the end of the war on February 25, 1991, he would fire another 31 Scuds at Israel.

The world watched as Iraqi Scuds rained down on Israeli cities, designed to strike as many civilians as possible. And at home, Israelis waited in their mamadim – their sealed bomb shelters – for their government’s response, growing increasingly frustrated.

Was this the Zionist dream? Sitting passively in a bomb shelter, waiting for the next missile, as the government in Jerusalem sat on its hands? Was this the country that Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir had given his youth trying to defend? Wasn’t the whole point of Zionism to be a safe haven? To make the world think twice about using the Jews as punching bags or political pawns?

So why did PM Yitzhak Shamir allow this? And how did the Israeli public respond?

The Israeli response

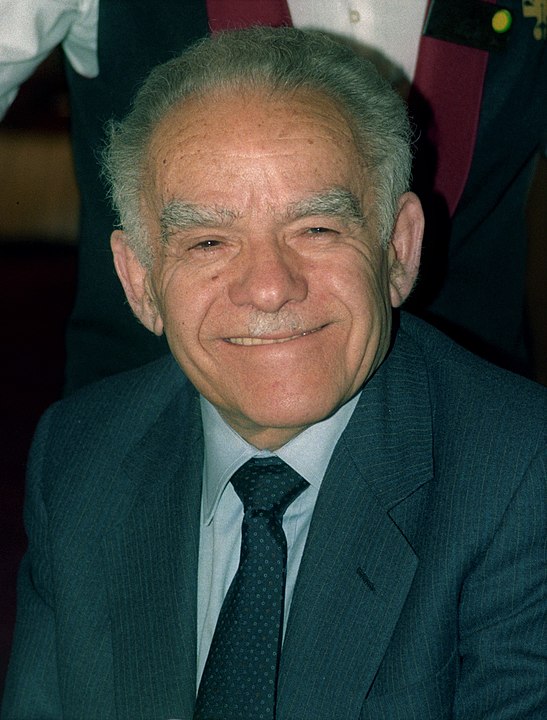

For starters, I want to be very clear: no one had expected the PM to show this kind of restraint – not even the PM himself! Like so many of Israel’s prime ministers, Shamir rose to power after a storied military career. His 2012 obituary in the NYT described him as an “unyielding” leader whose “victory came not from compromise, but from strength.” Even his last name – which he chose himself after arriving in Palestine in 1936, at the age of 20 – translated to “thorn” or “sharp point.”

Which was all too fitting, considering his past military posts. Because if the young Shamir was passionate about one thing, it was this: getting the British the heck out of Mandate Palestine, by any means necessary. So he became a high-level commander in the Lehi – the smallest, fringiest, and most hardline of Israel’s pre-state paramilitaries.

After the establishment of the state and the dissolution of the Lehi, Shamir spent almost 20 years as a Mossad agent abroad. And if you want to know more about the kind of wild stuff the Mossad gets up to, listen to the fourth episode of this season.

I’m telling you this because I want you to really understand that Shamir had dedicated his entire life to creating and then defending an independent Jewish state at any cost. He wasn’t shy about using force. The NYT described his brand of Zionism as “muscular.”

And yet, at the most crucial moment – as his cities were shelled by Iraqi missiles, his citizens cowering in bomb shelters – Shamir chose to fly in the face of his own instinct. As historian Avi Shlaim puts it: “[Israel’s] entire military doctrine is geared to seizing the initiative and going on the offensive… All of these tenets were violated by Israel’s passivity during the Gulf War. In fact, Israel’s traditional military doctrine was stood on its head.”

Israelis were baffled. Even prominent members of the left clamored for a military response. Israeli literary critic and scholar Dan Miron published a searing article in Ha’aretz, titled “If there is an IDF, let it appear!”, a pointed reference to “In the City of Slaughter,” Hayim Nachman Bialik’s iconic poem about the Kishinev pogrom. (Which you know all about, because you listened to the Kishinev episode of this podcast. Don’t worry, for a refresher, see the link in the show notes.)

The whole point of Israel’s existence (well, one of the points) was to prevent another “city of slaughter.” But now, Iraqi missiles rained on Tel Aviv. Saddam Hussein bragged “I will burn half of Israel.” And still, still, Shamir’s government remained cagey about the prospect of Israeli retaliation. Here’s Zalman Shoval, the Israeli ambassador to the US, describing Israel’s position:

“Israel has never ruled out the possibility of making a response to the attacks on her. But I would say that any decision the Israeli government may or may not take will necessarily have the character of retribution. It’s not a matter of an eye for an eye, it’s a matter of how to act in the best way in order to defend our population and in order to prevent attacks in the future.”

Adding fuel to the fire was the Palestinian response to Iraq’s attacks. Though the Scuds fell indiscriminately from January 18 to February 24, threatening Jew and Arab alike, many Palestinians openly celebrated the pummeling of Israeli cities – an outrage that Israelis never really forgave.

Imagine it. Over a month of sitting in a bomb shelter. Of watching your neighbors dance on their rooftops for a news camera, not even ashamed of celebrating your humiliation and fear. Not knowing whether the next Scud will be the one carrying a payload of chemical weapons. Not knowing when your government will finally respond, or not. How many Scuds would have to fall in Israel before the government declared “Enough!”?

And truth be told, Shamir was asking that very question. Because the PM was not sitting passively. A Times of Israel article reports that as soon as the first Scuds fell on January 18, Defense Minister Moshe Arens called up Dick Cheney and informed him of an imminent Israeli attack on Iraq. The IDF even picked out targets, including Saddam’s palace and Iraqi army HQ.

The Israelis went so far as to prepare for the mission. Here’s reporter Amir Oren, speaking in 2019: “Benny Gantz, who is now a candidate for the Israeli elections, at that time was a Lt. Col. in charge of an air force commando unit. He was aboard a helicopter on his way to take off from an Israeli air base and land in Iraq when the abort order came.”

But why? Why abort? Israeli military doctrine demanded a strong reaction! Was tiny, vulnerable Israel setting a dangerous precedent with its lack of action?

Shamir grappled with those questions. In his 1994 autobiography, he reflects, “There was… not one day on which I could be certain that our non-participation… would not in the end extract an even higher price from us than that which we were already paying.” So many of double negatives there, but you get the point.

Yet Shamir put aside his anxieties. And despite what author Gordon Zacks describes as the Israeli PM’s “bad chemistry” with President Bush, the two men worked closely together. Bush, of course, was anxious to ensure the stability of his coalition. And Shamir was a pragmatist. Zacks described that Shamir knew that if he attacked, the coalition would fall apart, and they would not be able to defeat Saddam. So, he didn’t react. As scuds fell, Shamir, and Israel, exercised restraint.

Not that it was easy. Shamir reflected that “I can think of nothing that went more against my grain as a Jew and as a Zionist… [This] was one of the hardest tasks I ever imposed upon myself.”

But Shamir did not choose restraint solely for Bush’s benefit. For one, there were limits to what Israel would accept. Had Iraq used chemical weapons, Israel certainly would have retaliated. Thankfully, that scenario never came to pass. But Shamir was also motivated by a certain amount of self-interest. As celebrated Israeli diplomat Abba Eban points out: “The truth is that we had no capacity to avenge our few tragic deaths without incurring losses of human life far greater than any that we had suffered.”

Because somehow, the Israeli death toll remained miraculously low. The exact stats differ depending on the outlet, but everyone agrees that fewer than five Israelis died as a direct result of the attacks. The missiles caused a handful of serious injuries, as well as a number of indirectly-related deaths due to heart attacks, asphyxiation, or incorrect application of atropine. Secular and religious Israelis alike called it a “miracle.” A scientific paper in Nature even tried to determine a scientific explanation for the low death toll.

Not that this made the winter of 1991 any less terrifying for Israelis. I can only imagine my old kindergarten classmate Uri, waiting patiently in his mamad in his child-sized gas mask, trying to catch some sleep. The war’s effects lingered well past its official end date. The rubble could be cleared, the damaged buildings rebuilt.

But the collective trauma wasn’t so easy to shake. Eban describes it like this: “We had lost the capacity for conventional punitive reprisal. We were forced to understand that we now had an adversary that we could not reach with our major weapons.”

Aftermath

Thankfully, the war itself did not last long. Though Iraq boasted the fifth-largest army in the world, it was no match for the American-led coalition. By the end of February – six weeks after the first American-led attack – Saddam had been routed from Kuwait, leaving him isolated, angry, and forced to agree to a cease-fire.

And the PLO, who had so enthusiastically, and frankly stupidly, supported Saddam? It, too, paid a price. According to Philip Mattar (mah-TAR), former executive director of the Institute for Palestine Studies:

“The 1990-1991 Gulf Crisis resulted in one of the worst setbacks for the Palestinians in modern times… By the time the crisis ended… the thriving Palestinian community in Kuwait had been destroyed, Gulf financial and diplomatic backing that had sustained the PLO for two decades had been withdrawn, international endorsement for Palestinian self-determination had declined, and the Arab consensus… in support of the Palestinian cause had been damaged.”

And if that wasn’t bad enough, more than 100,000 Palestinian workers were booted from the oil-rich countries that had fought against Saddam. And, as an al-Jazeera article says: “The Kuwaitis had financed a massive media campaign which called Arafat a traitor for supporting Saddam.” Yet again, the decisions of the Palestinian leadership had direct and unpleasant consequences for ordinary Palestinian people.

Arafat was backed into a corner. Ten months later, PLO negotiators sat in on the Madrid Peace Conference – the first time that Palestinians and Israelis entered any kind of negotiations.

And while Israel proved itself open to peace – both at the Madrid Conference and later, in Oslo – it nonetheless remained vigilant.

As I researched this episode, I couldn’t help but notice that all the Israeli sources I found drew a direct link between the 1991 Gulf War and today’s security situation. The Gulf War had exposed cracks in Israel’s ability to defend itself – vulnerabilities that the government and the military vowed to eliminate. They revised the specs for the bomb shelters – or “mamad” – that we mentioned at the top of this episode, mandating their presence in any home built after 1992. Such shelters are everywhere in Israel – public buildings, private homes, communal spaces.

Most importantly, Israel no longer relies on clunky, ineffective Patriot missiles from the United States. Since 2011, it has used a mobile air defense system called the Iron Dome, which intercepts and destroys short-range rockets. True, rocket attacks from Gaza and Lebanon are still sadly common. But they do not engender the same existential terror as Saddam’s barrage of 1991.

The Israeli government and military have explicitly stated that the country is prepared for another Gulf War-style threat from a faraway country intent on wiping Israel off the map. (We all know what country they’re talking about.) Because, as the saying goes, Israelis are always ready for two things: barbecue and war.

Five Fast Facts

So that’s the story of how the Gulf War reshaped the modern Middle East and put the Zionist ethos through its harshest test. Here are your five fast facts.

- In August 1990, Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein invaded his southern neighbor, Kuwait. Kuwait fell quickly, and the Iraqis looted, plundered, and pillaged their way through the tiny country.

- Almost everyone, including the UN Security Council, condemned the act. However, Saddam did enjoy support from the PLO, which was drawn to his fiery rhetoric and unwavering support of the Palestinian cause.

- Saddam refused to leave Kuwait. So in January 1991, an American-led coalition invaded Iraq. In hopes of provoking an Israeli response, Saddam fired 39 Scud missiles at Israel, and threatened chemical warfare. Miraculously, though Israel suffered serious property damage, few people were killed.

- The Americans cautioned that Israeli retaliation could jeopardize the American position. So PM Yitzhak Shamir chose not to retaliate. The war ultimately neutralized one of Israel’s major enemies – Iraq – without any Israeli intervention.

- The PLO’s vociferous support of Iraq cost them. Support for the Palestinian cause cooled across the Arab and Western worlds, and ordinary Palestinians were swiftly booted from their homes and jobs in the Gulf states.

Those are your five fast facts, but here’s one enduring lesson as I see it.

The Gulf War fascinates me for a number of reasons. Chief among them is the range of personalities involved. Every head of state could be a movie character. Saddam as the crazy but strategic villain. Bush as the powerful cowboy. And Shamir, whose behavior during the war defies glib categorization.

How did a former Lehi commander refrain from counter-attacking Iraq? Lehi! The organization that seemed to be constantly jonesing for a fight! And yet, in the face of a legitimate and immediate existential threat to Israel, Shamir adopted the policy of his old rival, the Haganah, a policy that the Lehi rejected time and time again: havlagah, or restraint.

But I think that actually, the Gulf War was Shamir’s finest hour. In the words of Pirkei Avot, chapter 4: “ אֵיזֶהוּ גִבּוֹר, הַכּוֹבֵשׁ אֶת יִצְרוֹ?” “Who is mighty? He who subdues his natural instincts.” Lao Tzu, founder of Taoism, said as much in the 6th century BCE: “If you understand others, you are smart. If you understand yourself, you are illuminated. If you overcome others, you are powerful. If you overcome yourself, you have strength.”

I love that. Resisting a counterattack took strength. Despite his strong personal feelings about the matter, Shamir clearly understood that a show of might could easily backfire, upending the delicate balance in the Gulf and possibly even shifting the war in Saddam’s favor. He was strong enough to see that despite the fiery op-eds in the paper, despite the public anger, despite the missiles, Israel would be better served by standing by.

But “standing by” is not the same as being passive. It’s not the same thing as being weak. Sometimes, standing by is actually strategic. It’s actually strength. And when he stood by, Shamir demonstrated this strength. And I personally can learn so much from Shamir, a man who overcame himself, his instincts, perhaps even his experience, and in so doing, demonstrated strength…real strength.

Bibliography

- Alston, Adam Eley and Katie. “The Ex-CIA Agent Who Interrogated Saddam Hussein.” BBC News, BBC, 4 Jan. 2017.

- “Saddam Hussein — Iraq’s ‘President for Life’.” The Christian Science Monitor, The Christian Science Monitor, 26 Aug. 1981.

- “Before The Revolution | Trailer.” YouTube, uploaded by Journeyman Pictures, 9 March 2016.

- “Persian Gulf.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

- “Saddam Hussein.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

- Riedel, Bruce. “Lessons from America’s First War with Iran.” Brookings, Brookings, 28 July 2016.

- “Iran-Iraq War.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/event/Iran-Iraq-War

- Ottaway, David B. “Gulf Arabs Place Reins on Iraq While Filling Its War Chest.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 21 Dec. 1981.

- U.S. Department of State, U.S. Department of State.

- “The Use of Terror during Iraq’s Invasion of Kuwait.” The War on Terror: Target Iraq | The Use of Terror during Iraq’s Invasion of Kuwait.

- Research, CNN Editorial. “Gulf War Fast Facts.” CNN, CNN, 29 July 2020.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. Accessed 27 Apr. 2022.

- Hammer, Juliane, and Helena Lindholm Schulz. The Palestinian Diaspora: Formation of Identities and Politics of Homeland, Routledge, London, 2005, pp. 67

- Khalidi, Rashid I. “The Palestinians and the Gulf Crisis.” Current History, vol. 90, no. 552, 1991, pp. 18–37. Accessed 28 Apr. 2022.

- Shlaim, Avi. “Palestine and Iraq.” MIFTAH.

- Post, Jerrold M. “Perspective on Saddam Hussein : Crazy like a Fox : He Is Narcissistic, Charismatic, Ruthless and Shrewd; He Will Do What He Must to Fulfill His Messianic Destiny.” Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Times, 25 Jan. 1991,.

- “Palestinians: What do you think about Saddam Hussein?” Youtube. Uploaded by Corey Gil-Shuster, 2 Jan 2019.

- Sciolino, Elaine. The Outlaw State: Saddam Hussein’s Quest for Power and the Gulf Crisis. Wiley, New York, 1991.

- Anfal Campaign and Kurdish Genocide – Department of Information Technology, KRG.

- Shapira, Anita. Israel: A History. London: Phoenix, 2015.

- Shlaim, Avi. “Israel and the Conflict.” International Perspectives on the Gulf Conflict, 1990-91, edited by Alex Danchev and Dan Keohane, St Martin’s Press, 1994, pp. 59-79.

- “The Gulf War in Israel, Explained.” YouTube, uploaded by Israel Defense Forces, 1 March 2021.

- “When Saddam Hussein fired salvos of Scud missiles into Israel 1991.” Youtube. Uploaded by l’ère Houari Boumediene. 8 January 2021.

- “News – Gulf War – Scud Missiles Hit Israel – Bush & Schwartzkoff News Conferences – 18 Jan 1991.” Youtube. Uploaded by Mary Van Deusen FanVids.

- Kifner, John. “3 Die, 96 Are Hurt in Israeli Suburb.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 23 Jan. 1991.

- فيديو video قصف اسرائيل فقط صدام فعلهالتقريركاملsadam hosin. Youtube. Uploaded by a7medasaaal.

- staff, TOI, et al. “‘Saddam Gave Orders to Fire Chemical Weapons at Tel Aviv If He Was Toppled in First Gulf War’.” The Times of Israel, 25 Jan. 2014.

- Shamir, Yitzhak. Summing Up: An Autobiography. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1994.

- Zacks, Gordon. Defining Moments: Stories of Character, Courage and Leadership. Beaufort Books, 2015.

- Eban, Abba. Personal Witness: Israel through My Eyes. Jonathan Cape, 1993.

- Gross, Judah Ari, et al. “’We’re Going to Attack Iraq,’ Israel Told the US. ‘Move Your Planes’.” The Times of Israel, 18 Jan. 2018.

- “Persian Gulf War: Israeli Ambassador.” C-SPAN, https://www.c-span.org/video/?15919-1%2Fpersian-gulf-war-israeli-ambassador.

- Brinkley, Joel. “Yitzhak Shamir, Former Israeli Prime Minister, Dies at 96.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 30 June 2012.

- “Gulf War Saddam Hussein Scud Attack On Israel Tel Aviv | Prince Hassan Bin Talal | This Week | 1991.” Youtube. Uploaded by Thames TV.

- “Iraqi Army: World’s 5th Largest but Full of Vital Weaknesses.” Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Times, 13 Aug. 1990.

- Mattar, Philip. “The PLO and the Gulf Crisis.” Middle East Journal, vol. 48, no. 1, 1994, pp. 31–46.

- Prusher, Ilene. “Palestinian Discretion Is Better Part of Valour.” The Irish Times, The Irish Times, 14 Nov. 1998.

- Hadida, Avi (Lt. Col). “The Reflection of Israeli Society in Popular War-Songs.” June 2015

- יוסי מימון – אדון סדאם סדאם המטומטם. Youtube. Uploaded by duduwar.