Schwab: Welcome to Jewish History Nerds, where we do exactly what it sounds like: nerd out on awesome stories in Jewish history.

Yael: I’m Yael Steiner, and my childhood dream was to stay in school forever.

Schwab: I’m Jonathan Schwab and I am in school forever. Yael, what awesome story in Jewish history do you have for us today?

Yael: I am so excited because even though we’ve really discussed some cool stories over the course of this season so far, this is the first one that I feel very confident in saying is totally, totally bonkers. We are going to be talking about a community of Jews on the eastern coast of Italy in a small, small village called San Nicandro, and in particular, their leader, a man named Donato Manduzio. And-

Schwab: I have never heard of him.

Yael: As we get deeper and deeper into this story, what you will learn is that in this tiny village of San Nicandro, in the 20th century, after World War I, there was a tiny, tiny group of people that converted to Judaism and thought they were the only Jews in the world.

Schwab: All right. That last part, obviously, is the most interesting.

Yael: So fascinating. And we’ll take a step back just to see how we get there.

Schwab: My major question is, how did they come to think that they were the only Jews in the world?

Yael: So San Nicandro is a tiny, tiny village on the Adriatic in what is known as the spur of the boot of Italy. And because of the landscape and the geography of that area, the village was extremely isolated. In fact, it was so isolated that Mussolini himself sent some of his enemies there for exile because it was so remote that the thought was these people would never find their way back to civilization.

And because it was so remote, it had very little access to the outside world, and so when Donato Manduzio decides to convert to Judaism, they only learned that there are other Jews in the world once a railroad comes in the 1930s.

Schwab: So he converts, his community converts with him. How long did this go on before they realized there are other Jews in the world?

Yael: So one of the amazing things about this story is just how fortuitous all of the timing is. So Donato Manduzio only decides to become Jewish and encourage his community members to become Jewish in the late 1920s. And then the railroad… It doesn’t come all the way to San Nicandro, but it comes close enough to San Nicandro that more visitors from the quote-unquote outside world are able to reach the village in the early 1930s. So it’s only a couple of years that they’re Jews and practicing Jews who believe themselves to be the only Jews in the world before they get exposure to new people in the village who meet them and say, “Oh, you guys are Jews? You should connect with those other Jews in Rome.”

Schwab: So their conversion is totally text-based? It’s not like a Jew comes-

Yael: Correct.

Schwab: … to town and tells them… Wow.

Yael: So… yeah, you realize, this would have happened 100 years earlier, and there would have been 100 years worth of Jews practicing in San Nicandro thinking they were the only Jews in the world. It’s just unbelievably fortuitous timing that it only goes on for a few years.

Schwab: We might go there a little bit, but I also think if a bunch of people started practicing a form of Judaism based on their reading of the Hebrew bible, that community might look a little different than other Jewish communities that have had, like, the full historical development of Rabbinic literature and, and all of that. That might be… I don’t know. That might be part of this story.

Yael: Did you know that they converted based on reading the Hebrew Bible, or are you just smart enough to figure out that that’s the only way that they possibly could have converted-

Schwab: I’m just guessing.

Yael: It was 100% the Hebrew Bible. Why don’t we start with how this gentleman got to this point. Donato Manduzio was born in 1885 in San Nicandro. He was a peasant, as were most of the people in that area. And in the 1910s he joins the Italian Army and fights in World War I, as do many or most of the men at that time.

Schwab: I definitely should know this, but remind me, Italy is on which side in World War I?

Yael: So it is actually quite confusing. Italy is on the Allied side in World War I with the United States and Britain.

Schwab: What we consider the good guys.

Yael: The good guys. But in World War II they’re part of the Axis powers with Germany and Japan, so I definitely understand the confusion.

Schwab: The bad guys.

Yael: Yes. So he comes back from World War I injured, and even though we have his diary, which is fascinating reading, we don’t actually know the nature of his injury. What we know is that his mobility is significantly impaired but he does not share with us clearly what that injury is. But the injury, again, itself is fortuitous. Obviously I do not wish him ill, I’m sorry for him that he was injured, but because he was injured, he was forced to convalesce in a military convalescent hospital, which was where he was taught to read.

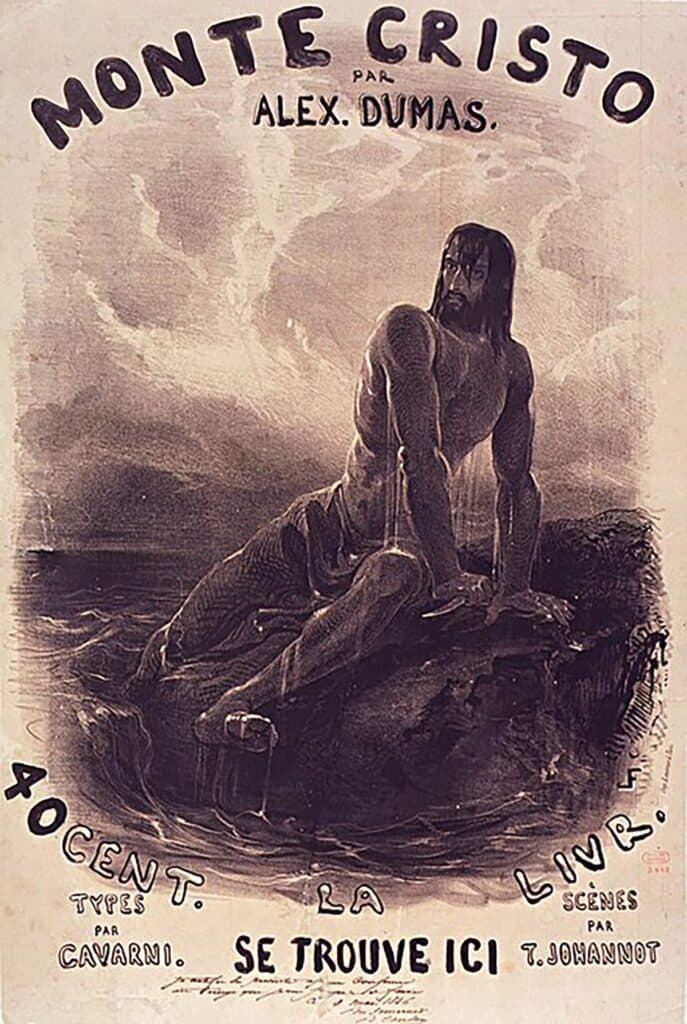

And he actually really loves to read, and he reads a whole bunch of different things. It’s brought to our attention that The Count of Monte Cristo was one of his favorite books.

Schwab: Hmm. That is a really good book.

Yael: It is. Alexander Dumas, or, you know, I’m not gonna pronounce it the other way.

Schwab: (laughs) No.

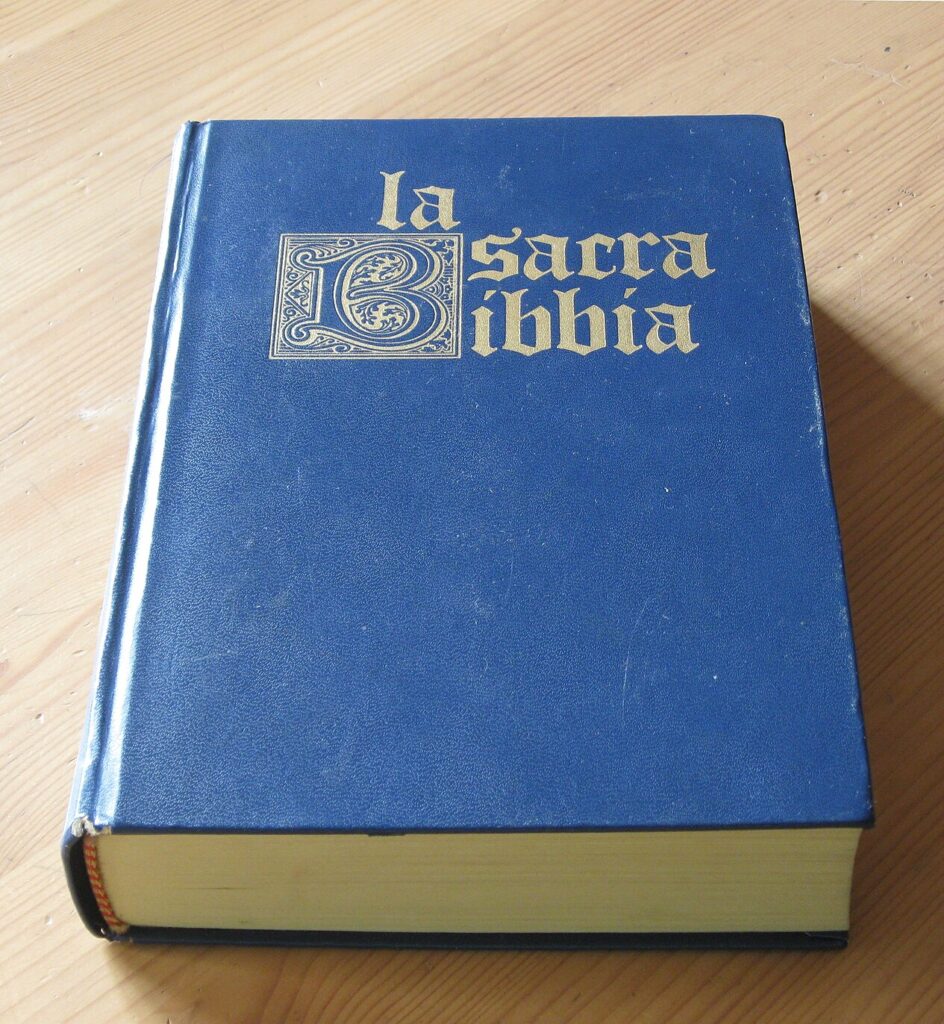

Yael: But he loves The Count of Monte Cristo. He reads a ton of different things. He reads romance, he reads almanacs. And ultimately someone gives him an Italian translation of a Pentecostal bible. And it’s interesting. One of the reasons why he may have gotten a Pentecostal bible is that in the 1910s and ’20s there was a phenomenon of people who had emigrated to the United States in the late 19th century, early 20th century to try to make money and better lives for themselves, but rather than sending for their families in Italy, they actually returned to Italy with the money that they had made, and stayed in Italy. And these people were actually quite influenced by some of the Christian revivals that were happening in the United States at that time and they brought back some of this evangelicalism.

So it is possible that the person who gave him this bible was trying to bring him over to the evangelical side.

Schwab: So there was a conversion attempt. Didn’t work out possibly the way it was intended.

Yael: I’m speculating, but it’s likely. So he gets this Italian copy of the Bible, and he is fascinated by it, and he likes himself. I will say this about Donato.

Schwab: Okay. Great. That’s a very important trait for people. Always enjoyable to read someone’s diary when they like themselves, ’cause it’s obvious.

Yael: He writes his diary in the third person.

Schwab: Sure.

Yael: He talks about what Donato Manduzio does.

Schwab: Addressed to who? Is he like, “Dear Diary, today, Donato changed the world?”

Yael: “Today a girl look at me in homeroom, and I sent her a note.” No, so he reads the Hebrew Bible. As I mentioned, He thinks a lot of himself. And he realizes that he doesn’t think Jesus is the Messiah. He thinks Jesus is a prophet, but he doesn’t think Jesus is the Messiah because there’s still way too much suffering in the world, and if the Messiah had come, there would be less suffering in the world. And-

Schwab: All right. You said he reads the Hebrew Bible? Not in Hebrew?

Yael: Not in Hebrew. But I’m referring to the Five Books of Moses or what we would refer to as the Torah.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. What I think he would have called the Old Testament but I guess he wasn’t calling it that.

Yael: The Bible that he was given. And then Donato has this self-proclaimed epiphany, vision. He, himself, gives two different accountings of the story. In one account he has a dream. In the other, he says, an act of God intervenes, to inform him that he really is supposed to be a Jew, and that the way that people lived in the Old Testament was the true path. He decides he’s going to live as a Jew. And he has remarkable sway with this small group of people in his village, because ultimately about 80 people join him to live as Jews.

Schwab: How does that happen? Like, what is it about him that’s so charismatic that other people are joining him on this very abrupt life change?

Yael: So it’s not clear, because while we do have a list of all the families that converted, none of them ever record for us what it is that drew them to the conversion, and to be clear, they weren’t hiding themselves away somewhere separate from the rest of their villages. They were continuing to live in San Nicandro, in some cases with members of their own families who did not want to become Jewish. In fact, a lot of the scholarship makes clear that women were a lot more drawn to this than men, and there were some families in which the women converted to Judaism and their husbands either didn’t or were only very begrudgingly taken along for the ride.

But nonetheless, whether it was charisma, personality, some other outside force that was going on in San Nicandro at that time, a few families, many of them cobblers… Donato was a cobber by trade.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. A very well-respected cobbler. He was very influential in the cobbler community.

Yael: Yes. He was the Manolo Blahnik of 1920s San Nicandro.

Schwab: That is not a reference I get at all.

Yael: It’s fair. And probably only, like, four people listening to this will get it. I don’t know what the Venn diagram is of people who watch Sex in the City and people who listen to Jewish History Nerds but we can put that to the side.

Schwab: But those three people will love it.

Yael: Exactly. So a bunch of cobblers and friends and neighbors of his all decide they’re going to follow him. And he casts himself as a prophet, but it’s not in the cult leader way that you might be thinking. Like, they don’t worship him. He does not put himself on an elevated platform above them. The way he casts himself as a prophet is more that, “I’m the one who was lucky enough to see that this is what we should be doing,” but beyond that, I don’t think it was really a-

Schwab: He didn’t get treated in any different way.

Yael: Correct. He was just another village Jew. And they really do observe their Judaism seriously-

Schwab: That was gonna be my next question. Like, what shape did this observance take?

Yael: Well, as you so intelligently realized, all of their information is coming from this one copy of the Bible, so they are observing Judaism in what one might call a neo-Karaitic way, because it’s solely based on the written Torah. So they only eat certain parts of the cow, for instance. While they are not schechting or ritually slaughtering their meat, because the information on how to do that comes from the oral Torah. They are still buying their meat from their local butcher in San Nicandro, but they are not buying certain portions of the cow that are not kosher. They observe Shabbat. They observed holidays. One of the big things for Donato is that he used the calendar and the moon to figure out when they should be observing certain holidays.

Schwab: Right. The way that the Torah describes it, right? Like, we have a calendar that was instituted by the Rabbis, by Hillel, I want to say.

Yael: Sounds right.

Schwab: We don’t have to do that anymore, but if you just went by the Torah you would actually calculate it.

Yael: And once he learns that there are other Jews in the world, one of the first things he asks for is a Jewish calendar. That’s really, really important to him because that is how he structures his Jewish life.

So let’s get to that part. So he decides he’s gonna be a Jew. He brings a whole bunch of his friends along for the ride. So they really believed there were no other Jews in the world, because when you read into the New Testament, the Jews have gone by the wayside.

Schwab: Oh, yeah. Right.

Yael: His belief was that when the Temple was destroyed, Judaism faded away.

Schwab: This is so fascinating because it’s like if aliens landed on Earth, and just had a copy of the Bible, what would their understanding of Judaism and Jewish history be, and like, this is sort of exactly what happened, you know?

Yael: And that’s why I think the timing is so crazy, because this could have happened to him… Even let’s keep it modern. In 1860 he could have learned to read and received a written copy of the Old Testament, and people could have been living like this for 80 years before they found out there were any other Jews. But because of when the railroad was built, it’s only two years later that peddlers and salespeople – I think those are the same thing. I was just trying to sound smart by saying two different words –

Schwab: Salespeople is what peddlers put on their resume.

Yael: Yes. They learned that there are other Jews in the world because these peddlers come and, you know, they meet Donato or they meet one of the approximately 80 other people in the village who are living as Jews, and they say, “Oh, you guys are Jews? Interesting. I met a Jew once in Turin. I met a Jew once in Venice,” or, you know, there was-

Schwab: And the San Nicandro Jews are like, “There are other Jews in the world?”

Yael: That is exactly their reaction, particularly when they found out that there were large Jewish communities not particularly far away from where they were. Because if you look at a map, it’s not that San Nicandro is so far from anything. It’s just really hard to access.

Schwab : It’s fascinating also, he fought in World War I. He got out of San Nicandro a little bit. Like, how did he not come across Jews?

Yael: That is a good question. We know for a fact that there were Jewish soldiers in World War I. I just don’t know where Donato was, and whether or not there were actually Jews fighting for Italy. And if they were, they probably were with Roman regiments or Venetian regiments. But that is a good point. It’s not as though he had never left San Nicandro.

And I think goes back to a point that you made, in an episode last season where you were talking about how your children were surprised that Christmas gets so much more airplay than Hanukkah, because in their lives there are so many Jews, and they don’t realize that Jews are a much smaller portion of the population than Christians, but it just goes to show you that this man could have gone to war, did go to war, and-

Schwab: He thought Jews were 0% of the population.

Yael: Exactly. Exactly.

Schwab: Did they call themselves Jews? Like, what was the word that they were using to describe what they were doing?

Yael: You are right. They don’t call themselves Jews. It’s something similar to the People of the Book or the People of the Torah. But once they learn that there are Jews out there, They go, “Oh, yeah. We’re Jews.”

Schwab: Yeah. I feel like that opens up a huge question of, like, what does that word mean? Like, when we say, “Jews,” what does that word mean?

Yael: A hundred percent.

Schwab: You know? Like, what is it that they believe themselves to be, and What would we identify, or, or what would any Jews identify as, like, this is what being a Jew is?

Yael: Well, that question comes into play very practically for them once they discover that there are other Jews in the world, because Donato Manduzio wants more resources. He really does seem to be very genuine in his observance. And so once he learns about these Jewish communities, he starts sending letters, and he addresses these letters… He doesn’t know who to send them to. He doesn’t know who these people are. He literally sends letters that are addressed to, “The Jewish leaders of Rome.” “The Jewish leaders of Genoa.”

Schwab: Right.

Yael: “The Jewish leaders of Turin.” And none of these letters get answered-

Schwab: Oh, that’s so sad. Because it didn’t go to the right place. They were like, “Are you looking for the Chief Rabbi?” And he’s like, “What’s a rabbi?”

Yael: And… No, they went to the right place, I think, but nobody either opened them or answered them because they thought they were crazy.

Schwab: Right.

Yael: Like, think about now, you know, emails that you get, or even comments we’ve gotten on this podcast.

Schwab: We get some comments, and reviews on the podcast that we don’t respond to (laughs) because Is it coming from a place of genuine curiosity, or what are you trying to get from us?

Yael: Correct, and so if they got a letter that said, “Hi, I’m the Prophet of San Nicandro and-” I mean, I don’t know exactly what it said, but most of the letters went unanswered until somehow the people in Turin say, “I think these need to go to Rome,” and it gets to the Jewish leadership in Rome, and they find this kinda crazy, and they start to interface with the Jews of San Nicandro, ultimately trying to figure out how genuine is their belief. And the fact that Donato is so persistent in the face of their hesitancy and in the face of them trying to put him off, they start to see him as being actually genuine, which is very surprising to them. And some influential people from Rome are dispatched to San Nicandro to see what is really going on, and some resources do start flowing into the community. Some books are provided, Jewish calendar, a menorah.

Schwab: … wait. A menorah. Hold up. Did they celebrate Hanukkah?

Yael: I mean, the Book of the Maccabees is part of the New Testament.

Schwab: Oh, right. Depending what where you’re getting your Bible from, whether the Book of the Maccabees is part of it or not, because this whole story sort of fits in with other stories that I’m familiar with of other communities that were very isolated in some ways. I want to say the Jews of Ethiopia who were separated from other Jewish communities early and didn’t even know about Hanukkah, maybe didn’t even know about either the destruction of the temple or the building of the second temple.

Yael: So you bring up two really interesting points, and then I kind of want to speed through some other details because we could talk about this for so long and there’s a lot of points I want to cover. One is that there is a Jewish scholar who, himself, was very involved in finding the Ethiopian Jews and bringing them back to the Jewish fold, who visits San Nicandro, and is the first non-Italian Jew to visit San Nicandro, and he takes it upon himself to be one of those people who goes around the world and tries to find all the Jews that are quote-unquote missing.

And there’s a distinction between the Ethiopian Jews, where he believes that these people are Jews from the ancient times that have just been geographically separated and he understands the San Nicandro Jews are Jews by choice but they are both groups of Jews that have been living Jewish lives separate from the mainstream.

That’s one thing. The other thing is that once some of these Roman emissaries get to San Nicandro and start learning more about the community, they bring with them the resources of a large Jewish community, among them, education, summer camps for the children, and Zionism.

Schwab: Of course. Summer camps have to go hand-in-hand with Zionism in the 20th century. That’s, like a must.

Yael: Yes, very much so. And, again, fortuitous – or maybe in this case not fortuitous – timing. We’re talking now about the 1930s. These are people living under Italian Fascism and Mussolini’s Racial Laws, which are enacted in 1938. Prior to the Racial Laws, Jews were doing okay because they were a recognized religious group that was allowed to exist, unlike the Protestants, because Mussolini’s Fascism wanted this Italianized society, and for him Italianized meant Catholic Because it had been Catholic up until that point.

Schwab: This is off topic a little bit, but do you know the, the meme format online of, like, “It’s only champagne of it comes from the champagne region of France, otherwise it’s sparkling this,” and people-

Yael: Yes.

Schwab: … use that for all sorts of things? So I saw something along the lines of, like, “It’s only Fascism if it’s in Italy, in the tradition of the Fasces, the Roman bundles of wheat that were put together. Like, otherwise, it’s just sparkling Totalitarianism.” So-

Yael: (laughs) That’s really funny.

Schwab: … the only true Fascism is Italian Fascism.

Yael: Right. So they were living under the true Fascism.

Schwab: The true Fascism. The real one.

Yael: Um, and also, we can’t go through this period of European Jewish history without mentioning the Holocaust. They were largely spared from the Holocaust. But, as we know, the Jews of Rome and the Jews of other areas in Northern Italy were not spared at all. So it was a particularly interesting time to be living as a Jew in Europe, and to be living as a Jew by choice in Europe.

Schwab: Yeah, wow.

Yael: Again, the timing of this is so bizarre. Absolutely crazy that it’s right before the railroad comes, right before Fascism, right before the Holocaust, and right before the founding of the State of Israel. So what ultimately happens is that a lot of the young people are educated in these summer camps, and through other resources, about Zionism, and they leave and they go to Israel in 1949. And I’m skipping a lot here. Basically, the Jewish community in Rome has to figure out, in the ’30s and early ’40s, “What are we gonna do with these people? Are they actually real Jews? What is their status?” And in 1946, I believe, the men in the community are circumcised. Not Donato. Donato says, “I’m enough of a real Jew. I’m a real Jew. There is nothing else I need to do to prove myself.” But the remainder of the men.

Schwab: Interesting, ’cause I feel like if you’re going off the text of the Torah, that seems like a pretty real one, you know? It seems kind of unequivocal-

Yael: Yeah, I can’t speak to what belied his decision, but notably he does not get circumcised. A physician comes to the community and circumcises the men. The physician himself notes at some point that while he had been involved in many conversions, it had never been in the context of a community of people who had converted by choice, and didn’t think there were other Jews in the world.

The liaisons from Rome helped the community secure a synagogue building, which was not to Donato’s happiness because up until that point they had been praying in his home, and the fact that they got the synagogue sort of decentralized his power.

Schwab: Hmm.

Yael: And that may have precipitated his decision to say, “Hey, guys, I’m the prophet. I don’t need to be circumcised.” Like, I think he was trying to maintain in some way the power and prestige that he had had from the beginning. They become fully accepted as Jews in the Jewish community of Italy in 1946, and Donato passes away in March, 1948, so a few months before the State of Israel was established.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: And in 1949, almost the entire community makes aliyah and moves to Israel. As of a few years ago, there were three Jewish women still living in San Nicandro. They were older women, and so I’m not sure if any of them are still alive or still there, but certainly-

Schwab: If they are and they’re listening, reach out to us, please. We’d love to hear from you.

Yael: Arrivederci. No, that’s the wrong thing to say. I don’t know what you’re supposed to say. Shalom aleichem!

Most of the people in the community made aliyah, not Donato. A, he dies in early 1948. B, I’m not sure that he was as taken with Zionism as the rest of the community was. This is totally speculative, but it does seem that as the outside forces of the other Jewish communities made headway in San Nicandro, Donato’s power diminished. And I don’t think, for him, it was all about power. He really was truly genuine in his observance, but, I don’t know that we would have made aliyah to a place where he would have really been just another Jew. But what happens to these Jews once they get to Israel?

Schwab: Yeah. Like, do they just integrate into the Israeli community, and are there, like, members of Knesset now that are just descendants of this original group of people-

Yael: Not to my knowledge, though there are many descendants of these people. A lot of them moved to the north. They were strong, they were farmers, they were outdoorsy, which was much to the new country’s benefit given that a lot of the people there were scrawny urban intellectual types.

Schwab: Yeah, I know the type.

Yael: (laughs) Do you? So that was helpful. And there are still farms today that are being run by descendants of the San Nicandro Jews.

Schwab: Hmm.

Yael: They’re part of Israeli society. There, I believe, in the past 10 to 15 years has been some question about their Jewish status, And it is very political, and I think that there are some members of the community who the powers that be have decided are not Jews. And I don’t know all the details there, so I don’t want to misspeak, but I’m glad that you mentioned that because I think that really takes us to what is the takeaway from this story, aside from the fact that it’s bonkers and insane?

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: One of the things that I really like about this story is that in addition to asking for calendars and other types of books, one of the things that Donato asks for in all of his letters to the heads of these Jewish communities, and that he asks for persistently… he asked for gramophone recordings of the temple worship, the Avodah that was done in the Temple. He thinks these recordings exist which they don’t.

Schwab: I’d love to get my hand on some gramophone recordings of the temple service.

Yael: And, that request is actually one of the things that really impressed upon the rabbis that this guy was genuine, like, this is how badly he wants to practice, is that he’s trying to get it right to the letter, to an extent that we don’t even have that information, um, ’cause they had been saying the Psalms of the Day, the shir shel yom, which is taken from the worship in the temple, and he wanted to do it right. He basically wrote in these letters, like, “We’re doing this but we don’t know how to do it, and we want to do it better.”

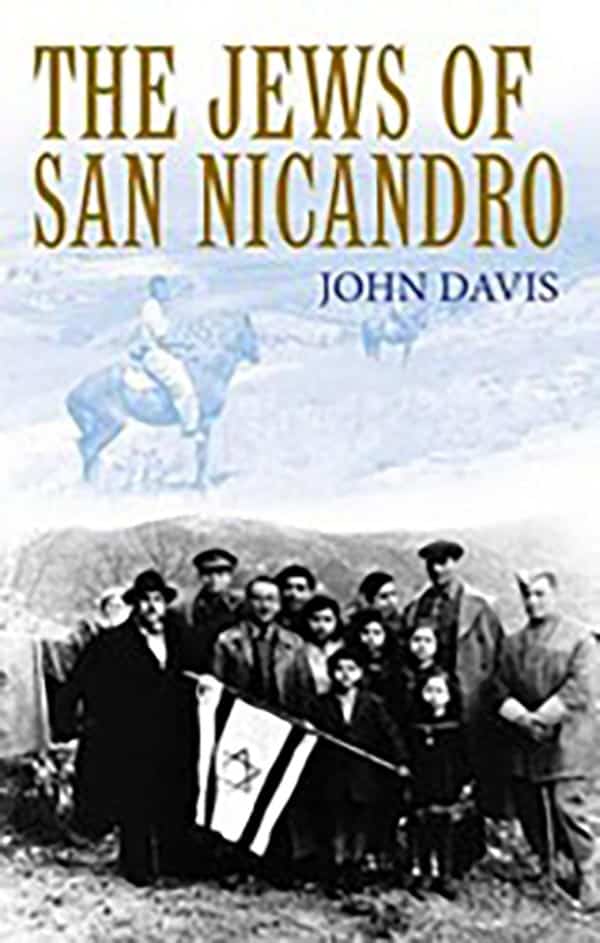

But back to your comment about the status of Jews in Israel today, I think that this entire story, which, again, has so much depth… And there’s an amazing, amazing monograph by a scholar named John Davis that I really recommend everybody read, It’s called The Jews of San Nicandro. Because it’s fascinating, and the detail and the stories are just unreal.

But the takeaway here for me is, what is a Jew? And this is something we’ve talked about a lot in this podcast, and obviously we’re not gonna answer it here today, ’cause I don’t know the answer, nor do I know if there should be an answer.

These are people who, by choice, joined the Jewish community, ultimately were accepted by the Jewish community in their region as full members, and are full members of the Jewish and Israel community today, though there are people now who question them, and, you know, this goes back to the tradition of the Khazarians who were Jews by choice.

Schwab: Yes, and, in the season and a half that we’ve been doing this podcast, I have come to think much more expansively, and be like, well, there’s actually a lot of different ways of being Jewish. Like, they sound like Jews to me based on everything you’ve said in this story. So I think there are a lot more types of Jews, and There’s a much wider range of Jewish identity, Than we typically think of.

Yael: A hundred percent. And one of the things I loved so much about this story is how modern it is.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Right.

Yael: There is a story about this in Time Magazine. In 1947 there is a story about the Jews of San Nicandro. So, you know, housewives in Indiana-

Schwab (laughs)

Yael: … were reading about this. it’s just mind-boggling to me that it’s so recent and so modern, and also how much the world has changed in the past 100 years. That less than 100 years ago there were people in Italy who didn’t know there were any other Jews in the world.

Schwab: Right. Even though it’s so recent, it seems like it would be so impossible to happen today.

Yael: it’s a really stark reminder of the rapid rate at which things change, and that’s what this story really reminds me of, and I think it’s very humbling to think… we have all of the information in the world in our pockets, as opposed to Donato Manduzio who had one Pentecostal translation of the Christian Bible, and then drew from that that the Old Testament had something to say to him, um, and where took him and where that took the descendants of this community, and who knows what the world will be like 90 years from now for Jews? To me it’s a very humbling story.