“Remember, say it again and again, you’re a boy. It’s Froyim.”

Those were the words Rena Quint’s father told her after she escaped the clearing out of the Polish ghetto she and her family were living in when she was just 6 years old.

Rena had just run away from the synagogue where the Nazis forced her mother and two brothers, along with the town’s other Jews, to gather in order to be deported.

“I was with my mother and two brothers, shooting going on, you can see the bullet holes,” she explained. “At the back of the door there was a man … and he said run. How does a kid run away from her mother? You’re holding on to your mother, you’re holding on tightly, and she must have been holding on to me, maybe my mother pushed me, maybe God pushed me, I ran out.”

That push, divine or not, ultimately saved Rena’s life. Her mother and brothers were sent to Treblinka– a new kind of camp just created, an extermination camp designed for only one thing– murder on an industrial sized scale. As many as 900,000 Jews were murdered in Treblinka’s gas chambers during the year and a half it was in operation.

When the Nazis deported the Jewish ghetto of Rena’s town it was only October of 1942, there were still nearly 3 long years to survive before the Allies liberated the camps.

Rena was born Freida “Fraidl” Lichtenstein in the Polish town of Piotrków Tribunalski in December of 1935. World War II came quickly to young Rena with the Nazis invading her hometown in 1939– forcing the Jews to live in a sealed off ghetto. At the time of the Nazi invasion, Poland was home to approximately 3.5 million Jews, and by the war’s end Rena was the sole survivor of her family– her mother, father, two brothers, and extended family were all murdered. All told, the Nazis murdered more than 3 million Polish Jews, 90% of the country’s community.

After she escaped from the synagogue a man found Rena and took her to her father who was working in a forced labor factory. Immediately there was a problem, the Nazis only wanted male workers, if they discovered that there was a 6 year old girl working there she would have been killed instantly, so they came up with a plan.

“My father hugged me but realized as a girl I couldn’t be there so we had a talk,” Rena recalled. “From now on you’re a boy. Your name isn’t Freida,” her father continued. “You’re 10 years old.”

“And I did,” Rena continued, they cut her hair and she started life as a boy in the factory. “I worked very hard, all kinds of things going on there,” her voice trailing off.

The Nazis constructed more than 44,000 mass incarceration sites across Europe during World War II. These centers included detention centers, ghettos, forced-labor camps (like the one Rena and her father were sent to) and the larger camps such as Auschwitz-Birkenau (the largest concentration camp constructed).

By the end of the war there were 20 main concentration camps in Europe and many had their own subcamps and forced labor sites employing the Nazi doctrine of “annihilation through work.”

Rena managed to survive alongside her father in the labor factory for some time, but as it became clearer and clearer that the war was ending the Nazis stepped up their extermination efforts.

Forced to Germany

“One day the Allies were getting closer,” Rena explained. “And when the Americans, or British, and the Russians were going through, the Germans started sending people out in Germany from the extermination camps, 6 of them, and the concentration camps.”

The Nazis, concerned that the war would be over soon, began a series of forced marches and deportations from the remaining camps in the summer and autumn of 1944. The purpose of these deportations were two-fold– to keep the slave labor apparatus running for the war effort and to remove all evidence of crimes against humanity.

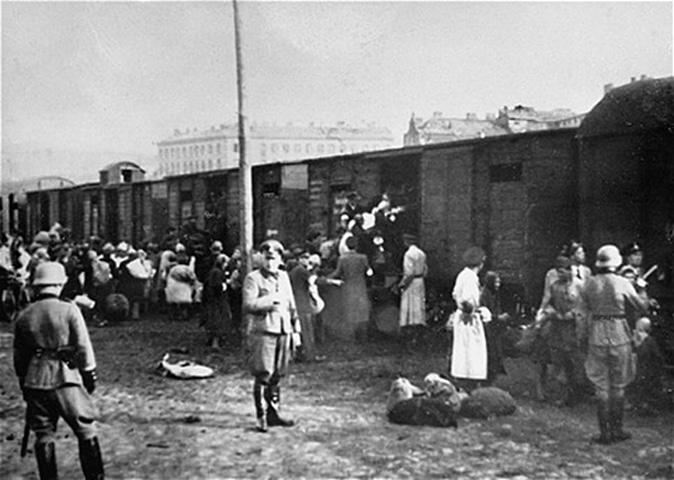

Hundreds of thousands of prisoners were either forced marched away from the nearing front lines, or in Rena’s case, transported on trains into the German heartland away from the advancing troops.

“We were put on these cars,” Rena said, holding up a black and white photo of a freight car. “Nothing to eat, nothing to drink, no toilet.”

The Nazis were meticulous in their calculations for these trains. Most of the freight cars used were 10 meters long (approximately 32 feet and 10 inches) and the SS manual on deportations suggested that each boxcar should carry 50 prisoners. The reality of this, however, was much more grim. Most boxcars were loaded with as many as 100 people, and during the height of the deportation of the Warsaw Ghetto to Treblinka in 1942, some trains carried as many as 7,000 victims in 50 car-long trains– putting as many as 150 people into each boxcar.

Life at Bergen-Belsen

Rena and her father were eventually taken to Bergen-Belsen, in northern Germany, the same concentration camp Anne Frank was deported to.

“Men on one side, women on the other,” Rena explained about the day they arrived.

“We got a problem because I was with the men and when you get into the camps the first thing you have to do is get undressed,” Rena continued.

“[My father] met a school teacher, he asked her if she would keep an eye on me, promised me that we would meet me in our hometown, war is going to be over soon,” her voice once again trailing off.

“He didn’t keep his promise. I never saw him again.”

With her father now gone, Rena, only around 10 years old, had to face the selection process on her own.

“We had to get undressed and leave everything in piles. I was holding a picture and one of the soldiers thought maybe I had a diamond or money right up in my hand,” Rena remembered.

“Tore up the picture. I have no idea what my mother looks like.”

Alone in the camp, Rena now had to face her new reality.

“Every day in Bergen-Belsen when we came out we got a blanket, we’d find women to get a blanket, every day the women would take their blankets, put a body into it and just throw the body some place out.”

As time passed Rena grew sicker and sicker and became worried that she too would end up like so many other people she knew, in a blanket thrown out in the trash.

“One day I was very sick with typhus, and I found myself living in dead bodies lying under a tree.”

It was early 1945 and a typhus epidemic was spreading throughout the camp, killing 17,000 people, including Anne Frank.

“I was lying there half dead, everyone else… this one died, this one died,” she explained. “And soldiers came in wearing different uniforms, speaking a different language and they said ‘we are the British Army, we have come, we have brought you food.’”

With British and Canadian forces closing in, on April 11th, 1945 Heinrich Himmler agreed to have Bergen-Belsen handed over without a fight. The camp was finally liberated on April 15th by the British 11th Armored Division without any resistance. Inside the camp Allied forces found 60,000 prisoners, many near death, dying of starvation or seriously ill. They also found 13,000 corpses lying around the camp unburied.

A BBC reporter attached to the 11th Armored Division described the scene the soldiers found:

Here over an acre of ground lay dead and dying people. You could not see which was which… The living lay with their heads against the corpses and around them moved the awful, ghostly procession of emaciated, aimless people, with nothing to do and with no hope of life, unable to move out of your way, unable to look at the terrible sights around them … Babies had been born here, tiny wizened things that could not live … A mother, driven mad, screamed at a British sentry to give her milk for her child, and thrust the tiny mite into his arms, then ran off, crying terribly. He opened the bundle and found the baby had been dead for days. This day at Belsen was the most horrible of my life.

Despite being liberated Rena still faced enormous odds to survive. By the end of April, 9,000 freed Bergen-Belsen prisoners died, and by the end of June another 4,000 had died.

Leaving Europe

“Where do I want to go? I don’t have a mother, I don’t have a father,” Rena asked.

Eventually Rena made it to Sweden where she was adopted by a fellow Holocaust survivor but tragically her new mother passed away just months later. In 1946 Rena was granted permission to immigrate to the United States with another adoptive mother, but she too tragically died just 3 months after making the trip.

Rena’s situation was very common. Death did not end after liberation for Holocaust survivors. In the immediate weeks following the liberation of the concentration camps 30,000 prisoners died and many more continued to pass away from health complications in the following years.

Once in the United States Rena was adopted by Leah and Jacob Globe, a Brooklyn couple in their 40s who had never had children. The Globes renamed Freida to Rena, the Hebrew translation of her Yiddish name, Fraidl, which means joy.

Rena received her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in education and worked as a teacher in New York. She got married to the love of her life and had four children, taking them all as adults later in life to live in Israel in 1984.

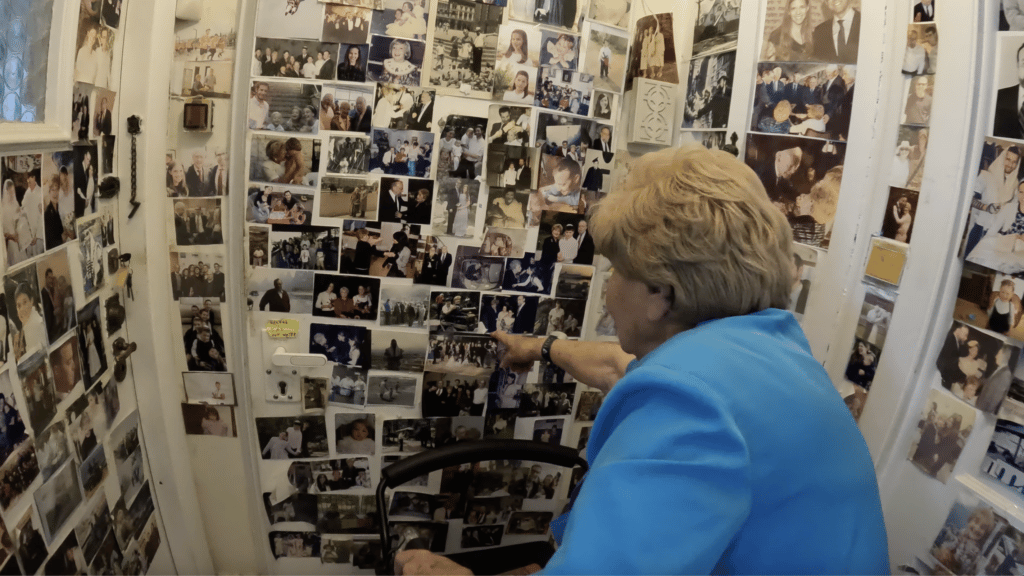

Rena lives up to her namesake– joy– and has devoted her life to spreading it. Her Jerusalem apartment is filled with photos of her and her husband with famous people, photos of the family, and dotting the walls are years worth of handwritten love notes left by her husband.

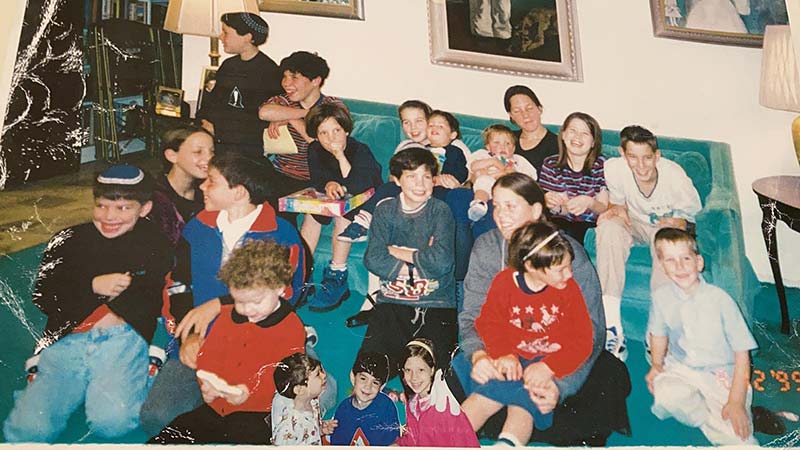

Today, Rena’s pride and joy is her family which has grown exponentially. On top of her four children, Rena now has 22 grandchildren and 43 great grandchildren.

In the summer of 2022 she was part of the delegation who met President Joe Biden at Yad Vashem, where she has been volunteering for the last 30 years as a docent.

“He said sit down, sit down,” she told me. “The first thing I told him was that I’m so honored that he came to Israel and to Yad Vashem, and he said can I give you a kiss?”

“And then he told me about his tragedy, his first wife and baby daughter were killed, and he was very happy to see that as bad as things were for us we went on with our lives.”

Reflecting on the moment one more time, Rena looked out across her shaded balcony in Jerusalem and added one more thing, while sitting in the late summer sun.

“Life is beautiful,” she said with a smile, nodding her head in affirmation.

@jewishunpacked “Say it again and again, you’re a boy.” Meet Rena a survivor who lost both parents during WWII and survived under incredible conditions. #jewish #inspiration #history #hope #poland

♬ Traditional Jewish Music: Shalom Aleichem (Clarinet Solo) – mbanksbenson

Originally Published Oct 24, 2022 11:55AM EDT