Reform Judaism and Zionism started at around the same time– two very different movements, both trying to address the same problem. So why were so many in both of these groups against the other movement? And how does understanding this divide help explain why Judaism is experienced so differently in America and Israel still to this day?

Facing a crisis

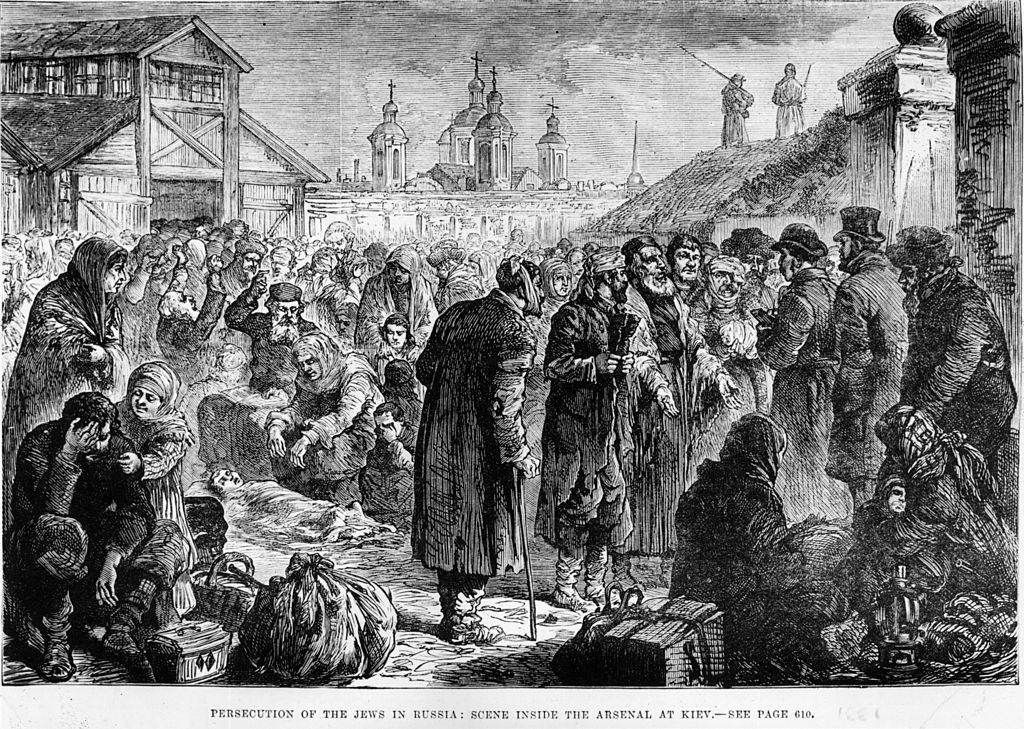

In the late 1800s, Judaism was facing a crisis. Antisemitism (a word invented in the 1870s—but a concept that’s been around for thousands of years) was on the rise. There was a serious concern that Judaism would disappear; and while to some that may seem sensationalist, it’s hard to write off as just some doomsday-sentiment, considering the horrible events that happened next– World War Two and the Holocaust.

The question on so many people’s minds was: “How will we survive?” There were many solutions proposed to that question. And in this article we are going to focus on two of them: One, a plan to more fully integrate into countries where Jews lived. And the other was the desire to form a Jewish homeland. In other words: Reform Judaism and Zionism. This was no lighthearted disagreement. So, let’s take a look at both.

Reform Judaism

While Reform Judaism started in Europe, it became dominant in the U.S. In the U.S., Reform Jews felt that they were home. America, to them, was the Promised Land. They had made it. And because of that, they wanted to fit in in that new home. So they emphasized parts of Judaism that could resonate with their non-Jewish neighbors. They took issue with many of Judaism’s rituals and laws—like rules around Shabbat and Kosher—and instead emphasized the more universal Jewish values, like “repairing the world”.

They also got rid of parts of Judaism that they believed could be considered offensive or antiquated. In 1885 in the Pittsburgh Platform, which spoke for many, but certainly not all Reform Jews, it said:

“[We] expect neither a return to Palestine (Israel) […] nor the restoration of any of the laws concerning the Jewish state.”

In other words, “We’re not interested in being a separate ‘nation” apart from others.” At the time Reform Judaism didn’t see it as something Judaism was supposed to be doing. Essentially, it was a strong rejection of Zionism.

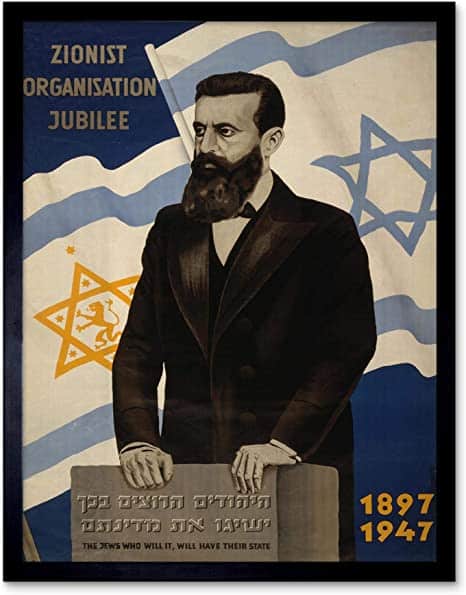

Zionism

So…what was Zionism? Zionism was the desire for Jews to re-enter the world stage as their own nation, once again. A prominent leader of that movement was Theodor Herzl, and he was specifically looking for a place of refuge for mostly Eastern European Jews. In his view, no matter how culturally assimilated the Jewish people were, they would never be seen as equals.

While early Zionist leaders didn’t agree on everything, one thing they certainly did agree on was that the Reform Judaism’s approach wasn’t going to cut it.

1930s

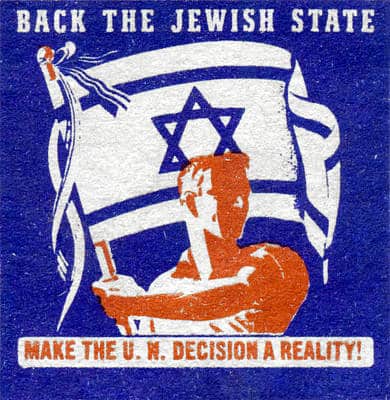

By the 1930s, many leaders of Reform Jewry began to change their tune, as they saw the rising hatred in Europe, and recognized that their solution to integrate was not going to work for everyone. As some within the movement (i.e. Gustav Gottheil, Stephen S. Wise, and Abba Hillel Silver) had been arguing for decades, it was no longer viable to reject Zionism. Jews were clearly in grave danger and needed a place of refuge—even if they themselves never planned on moving there. Fifty years after the Pittsburgh Platform, Reform Judaism’s official platform changed, now saying:

“Judaism is the soul of which Israel is the body. […] In the rehabilitation of Palestine, the land hallowed by memories and hopes, we behold the promise of renewed life for many of our brethren. We affirm the obligation of all Jewry to aid in its upbuilding as a Jewish homeland by endeavoring to make it not only a haven of refuge for the oppressed but also a center of Jewish culture and spiritual life.”

Columbus Platform

Even though Reform Judaism now officially accepted Zionism, that didn’t mean they saw eye to eye with leading Zionists. Judaism and Jewish life was evolving differently in America and in Israel.

Israel

The aim of the early Zionists was to demonstrate the importance of Jewish self-autonomy in responding to the antisemitism that was prevalent throughout the world.

But it was also more than that: they believed that Judaism, if given the chance to operate autonomously, could teach the world something profound. Judaism could promote a certain set of values, a certain way of life. But to do that, they needed to circumscribe themselves as a distinct nation in a homeland. Only in that way—living within defined borders, marching to the beat of Jewish life and the rhythm of the Jewish calendar, speaking the Jewish language and cultivating the Jewish culture—could they achieve a full expression of Judaism.

America

In America, meanwhile, many Jews felt that in order to have a future, they needed to more fully integrate within society and fit in with other cultures. In other words: to be a “man in the street, and a Jew in the home.” While Reform Judaism is our focus, it was true for all of the movements. American Jews believed they had to find commonalities, places where their values overlapped and they could work together with non-Jews if they were going to succeed. It was true then and it’s true today.

Today

It’s part of why today, many Jews in America (Reform and otherwise) don’t fully understand what it means to be Jewish in Israel. The difference between being pushed towards more universal values, like in America, or more particularly Jewish ones, like in Israel. There are parts of Jewish life that can only come out by living in a Jewish country. Only in Israel is your Jewishness inescapable, regardless of how religiously observant you are. The majority of Israelis are not fully observant, but still feel very Jewish. It’s everywhere, imbued into almost every institution. It’s the people you’re friends with and the places you go. It’s the food you eat, the news you watch, the signs you see alongside the road. And that is unique. It’s a way of thinking about Judaism that most world Jewry are simply unable to replicate. And yet, it’s a model for what’s possible.

And many Jews in Israel still don’t understand or even know about elements of Jewish life that happen outside of Israel. They cannot imagine the idea of religious life totally separated from the state—and the many implications of that separation. The idea that religious life is entirely voluntary, and outside the rhythm of a state is unimaginable. The freedoms, opportunities, and yes, challenges that come with this construct, are often foreign to Israelis. What would Judaism look like if it were free of political considerations?

How can Israelis keep learning from Jews in other places? And how can Reform, and all Jews living outside of Israel, find a way to learn from Israelis? We’ll never be the same, but it’s too easy to just reject the other side. To say that, from our perspective what they’re doing is not worth learning from. It’s much harder to continue asking “How can I keep learning from a side that lives a very different Jewish life than me in so many other ways?” But only in asking that, can the Jewish People continue to grow as one people, Am Yisrael. With almost half of world Jewry living in Israel, and half living outside of Israel, it’s clear that even as we disagree, we’re most certainly in it together.

This series is part of a partnership with the Z3 Project. More about their work can be found here.