Yael: I also have to confess that whenever I say the word Inquisition, I am immediately transported to a scene from Mel Brooks’s History of the World where there is a song about the Inquisition that, depending on your sense of humor, is either hilarious or completely inappropriate.

Schwab: I’ve only ever seen it in meme form, is that the… nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition.

Yael: That is Monty Python.

Schwab: Oh wow.

Schwab: Welcome to Jewish History Unpacked where we do exactly what it sounds like, unpack awesome stories in Jewish history.

Yael: I’m Yael Steiner, and my childhood dream was to stay in school forever.

Schwab: I’m Jonathan Schwab. And I am in school forever. Yael, we’ve had a couple of really interesting episodes, and the bar is pretty high. So what are we gonna talk about today?

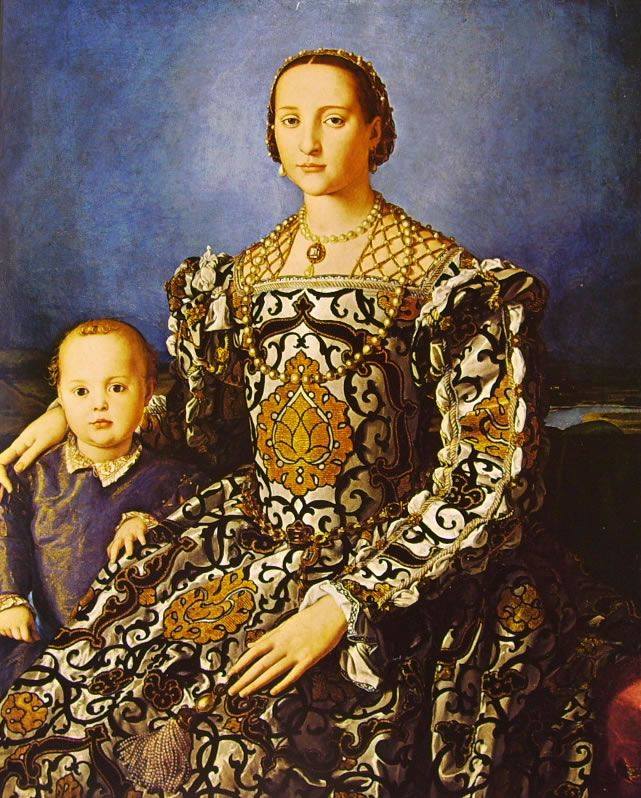

Yael: Well, I’m gonna raise the bar even higher, because today, we’re gonna talk about two really awesome empowered cool Jewish women in 16th century Italy who had a major impact on the political and economic circumstances of their communities.

Schwab: Two women, you said?

Yael: Yes, two different women, Dona Gracia Mendes Nasi and Dona Benvenida Abrabanel who, yes, is the niece of the famous biblical commentator, the Abrabanel.

Schwab: Wow. Very cool. So what did they do exactly?

Yael: Well, before I tell you what they did, which is, come out on both sides of an economic boycott, I’ll give you a little bit of background of where they were from and what was going on in that region of the world at that time. So the Ancona Affair, as this boycott is referred to, took place in 1555.

Schwab: And that’s an amazing title, by the way, the Ancona Affair.

Yael: The Ancona Affair. I know, it’s very saucy. It took place in 1555, also a cool sounding year, in the Italian port city of Ancona which is on the eastern coast of Italy, southeast of Venice and on the west coast of the Adriatic Sea across from Croatia because I know you’re a geography buff.

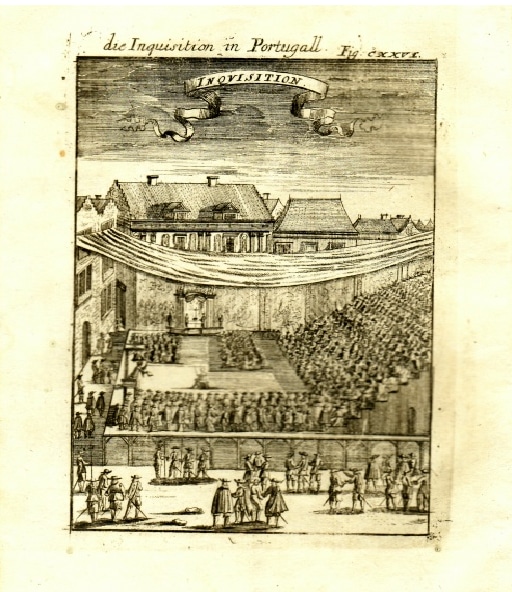

Jews lived in Ancona very successfully at that time. And as some of you may recall, 1555 was less than a century after the 1492 expulsion of the Jews from Spain. And many of the Jews in Ancona had migrated there due to that expulsion, or to the Inquisition, which started a century prior to that in 1390.

Schwab: So these are Jews with Spanish roots who moved over to Italy.

Yael: Yes. And interestingly enough, Benvenida and Dona Gracia came sort of on different sides of the coin of Jews who migrated out of Spain because of the Inquisition or expulsion. Dona Gracia’s family was forcibly converted. We’ll call those people who forcibly converted conversos.

They’re also occasionally in history referred to as Marranos. I’ve recently learned that Marranos is a more derogatory term, and converso is the more appropriate way to refer to them, as they were called Marranos by their detractors, because Marrano was a term for swine.

So yes, Dona Gracia came from a family of conversos. They first migrated through Portugal where they converted to Catholicism, but were really living, um, as crypto Jews. There were Jews, um, who externally had converted but were still maintaining a lot of their Jewish heritage.

And Benvenida’s family were Jews who fled Spain and never converted, and were never part of the converso or crypto-Jew community. And we’re just gonna call them Jews, even though obviously both groups of people are Jews but for convenience sake, uh, in this context.

Schwab: So you said the Inquisition and the expulsion. Just to remind me, those are two different things. Is one part of the other?

Yael: So I think I always thought they were the same thing. Apparently, the Inquisition began in 1390. And I actually didn’t realize this. It continued in some parts of Spain until the 19th century.

Schwab: Wow. So that had already been happening, the forcible conversion.

Yael: That had been happening for quite a while actually. While the Jews had enjoyed actually quite calm, peaceful coexistence with the Muslim community that they had lived under since the 8th century, there was a lot of conflict between the Jews and Christian Catholic community.

And I’m not exactly sure when. But definitely prior to 1390, in order for people not to be persecuted, killed or forced to flee their homes, many, many Jewish families forcibly converted to Catholicism.

Schwab: So, so then the Inquisition is making sure that they’re doing what they’re supposed to be doing.

Yael: Exactly. In 1390, I believe in the aftermath of a riot of some kind, there came to be a concern or a growing concern that a lot of these conversos were actually still practicing Judaism or associating with the Jewish community and connected to their Jewish roots. So while I had always thought that the Inquisition was a persecution of all Jews, what I learned while doing the research here is that it was actually an Inquisition of the conversos in order to ensure that they had really completely abandoned Judaism. So the people who never converted-

Schwab: They’re not really the targets of the Inquisition.

Yael: They are not the target. It’s really the quote unquote “Christians,” who used to be Jews, who are the targets of the Inquisition.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. That is interesting ’cause I’ve always similarly thought, you know, the Inquisition is, is this terribly antisemitic, you know, oppression of Jews which it is, it sounds like. (laughs) But not all Jews.

Yael: I also have to confess that whenever I say the word Inquisition, I am immediately transported to a scene from Mel Brooks’s History of the World where there is a song about the Inquisition that, depending on your sense of humor, is either hilarious or completely inappropriate. I think that’s the case with a lot of Mel Brooks’s humor.

Schwab: I’ve only ever seen it in meme form, is that the… nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition.

Yael: That is Monty Python.

Schwab: Oh wow.

Yael: But there’s this whole song which I’m not gonna sing for you about the (singing + playing song).

Schwab: You said you weren’t gonna sing it, and then did sing it (laughs) which I like.

Yael: Anyway, that song is going through my head. And when I visited Spain in 2019, I sang that song the entire time we were there. And my friend that I traveled with found it both super annoying and like, she was a little sensitive to it because her family is Sephardi. And what I think is really interesting traveling with her in Spain is that, you know, Sepharadim, especially those who are connected to their heritage, this is so much more of a profound topic in Jewish history, deeply felt topic. Then, for me as an Ashkenazi Jew whose grandparents were Holocaust survivors, I think she felt very similarly about our travels in Spain as I felt about travels that I’ve had in Eastern Europe. And it made me really actually conscious of the fact that I don’t treat longer ago Jewish tragedies the same way I treat more modern Jewish tragedies in terms of the way I process them.

Schwab: Makes a lot of sense, right? Like if your grandparents are Holocaust survivors, you think about the Holocaust so differently than-

Yael: No. For sure. And this goes back to what we talked about with Josephus where when things really pass into time, we don’t actually know what happened or we feel a lot more detached. So that was a real wake-up call for me, if, I want future generations of Jews to understand the Holocaust and the pogroms and the Crusades and the expulsion and all these terrible things that happen to Jews that I need to be more cognizant myself that just because something happened 500 years ago and not 100 years ago that it is important for me to learn and understand it on a deeper level.

Schwab: Well, if you wanna learn more about Jewish history, can I recommend a great podcast too? (laughs)

Yael: Oh my God, please do. I-

Schwab: Jewish History Unpacked.

Yael: I have taken us so far astray right now. but let’s get back to what we are supposed to be talking about, which is Dona Gracia and Benvenida.

Schwab: So they come from two different sides of the Inquisition. And does that… I’m really curious. This might be a spoiler for this story. But does that come into play? Do they have very different outlooks on like what it means to be part of the Jewish community because of their backgrounds?

Yael: It totally comes into play when we get to the point in time when we talk about this boycott of the port in Ancona. They both are economically powerful women. And one thinks we need to use that power to protest the pope and protest ways in which Jews are being persecuted. And one thinks that if we use that power, we are possibly going to inflict further harm on other Jews.

And I think that often plays out today in how Jews choose to exercise their political and economic power. So it definitely impacts their thought there. Um, let’s go take a few steps back to how we actually get to that point. As I mentioned in 1492, there is a major expulsion of Jews from Spain upon edict from Ferdinand and Isabella.

Schwab: It’s always easy to remember what year that happened. (laughs) Something else also happened. (laughs) Yeah.

Yael: It’s like, I think that if you took a poll of American students… Or maybe most American students don’t know about the expulsion. I honestly don’t know. But if you took a poll of like American Jewish students. The only royal couple in history they probably know is Ferdinand and Isabella. (laughs)

Schwab: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah.

Yael: Um, so Ferdinand and Isabella of Nina, Pinta and Santa Maria fame signed this edict, uh, expelling Jews from Spain. And at that point, Jews migrated all over not only the Iberian Peninsula but all over Europe many made their way up to Amsterdam. You may know that there was a large Spanish Portuguese synagogue in Amsterdam that later, not relocated, but also opened a location in New York which still exists today.

Schwab: That’s called the Spanish Portuguese Synagogue.

Yael: Yes. Like the Ohio State University. So that community of Spanish and Portuguese Jews in Amsterdam really originated after the expulsion. That was one of the places where Jews lived more comfortably after the expulsion. So fast forward a couple of years from the expulsion and Jews are living all over Europe and they’re living in Ancona in Italy in 1555, and they’re actually living relatively comfortably. They, over the course of those couple of decades, had made lives for themselves that were relatively economically prosperous, not all of them, but certainly some of them.

And the reason why this was the case was that, Pope Paul III was relatively tolerant of the Jews and didn’t really care one way or another that they were in Italy a particularly a-

Schwab: Relatively tolerant in like 16th century Europe means he wasn’t like actively killing them or preventing them from doing anything?

Yael: Correct. Exactly. Like he just wasn’t really paying attention to them. He didn’t mind that there were even crypto-Jews, people who were living externally as Christians, but were still maintaining some of their Jewish traditions. Like I’ll be completely honest with you. I have no idea what was going on in the rest of Italy or European history at this particular moment. So it’s completely possible that he was like totally otherwise engaged in other things. And this was very low on his to-do list or it’s possible that he just didn’t hate Jews as much as some of the other leaders of the church at that time. But he basically left them alone.

Schwab: He probably didn’t like Jews. But he didn’t hate them as much. I think it’s like a good way.

Yael: Correct. And they were kind of keeping to themselves and helping the economy at least in that part of Italy. But what happened is that Pope Paul III died. But his successor, Pope Paul IV, was not nearly as tolerant or willing to ignore the Jews particularly the crypto-Jews in Ancona. He was very concerned about the people who had converted to Christianity but were now backsliding into their Judaism.

Schwab: It’s a classic problem to have as a pope.

Yael: Yes. (laughs) Even if you were forcibly converted, once you are baptized under the doctrine of the Catholic Church, you are a Catholic. And that means that if you still have your Jewish beliefs or Jewish practices, you are committing an act of heresy. Um, and generally acts of heresy don’t go over super well with popes, is my understanding.

Schwab: They’re into people following the doctrines that they believe in.

Yael: Yes. I mean most religious leaders are. We’re not pinning it all on popes.

Schwab: Yeah. (laughs) Seems pretty fair.

Yael: Um, so He was concerned about that. And he did, take a lot of action to persecute crypto-Jews and conversos.

Schwab: In the hopes that they’re going to take this persecution and then become good Catholics, or just ’cause he didn’t like them very much?

Yael: That’s a great question. I don’t know what his goal was. Was his goal to persecute them and ultimately have them killed or expelled, or was his goal to have them repent and return or turn for the first time to a pure Catholicism? I’m honestly not sure. That’s a great question. But what I can tell you is that they persecuted many of these crypto-Jews using a lot of the methods of the Inquisition which were inflicting torture, asking questions about your true beliefs. And, it really took a great toll on the Jewish community in Ancona. And ultimately, he ordered 26 Jews, crypto-Jews to be burned at the stake.

And one of the 26 actually killed himself prior to being burned at the stake. But ultimately, um, at least 25 were burned at the stake for this sin of heresy.

Schwab: Publicly, like for the entire, you know, community to see.

Yael: Yes. From what I understand, those who enroute to being burned at the stake were willing to confess to their sins that they had maintained some semblance of Judaism in their lives were suffocated prior to being burned at the stake which I think was considered a minor act of mercy.

Schwab: Jeez. Okay.

Yael: Um, but those… Those who did not confess, uh, were burned alive. So really, really terrible, terrible, um, incident. And I believe that there are some ritual poems that are read on the, um, Jewish fast day of Tisha B’Av that have been written about this. Really an, an awful, awful tragic situation. And this is where we get to the political moment that, uh, Dona Gracia and Benvenida were involved in.

So in the wake of this burning at the stake, Dona Gracia who was a Portuguese Jew who had lived as a converso in Portugal ultimately made her way to Constantinople where she was living as a Jew. Um, she had always maintained a tie to her Jewish life.

Schwab: I don’t know why. But it feels like Constantinople comes up in almost every episode. (laughs)

Yael: Sorry, listeners. So she had made her way to Constantinople where she had a considerable amount of economic and political power. I know that there are probably a lot of people asking, how did these women have considerable economic and political power? They inherited their money from their husbands. They were widowed.

And that was really the only way that women in that era were able to attain personal wealth and any kind of power. It was bequeathed to them with the money that they inherited from their husbands.

Schwab: And is that because they didn’t have sons or their husbands didn’t have brothers?

Yael: honestly, I can’t remember which one or if it was both of them. At least one of them had sons. And there was some controversy that, uh, she was left the money and not the sons. I think it was Benvenida because I know that later in her life there was a major controversy over inheritance.

Schwab: Maybe, it wasn’t totally coincidental. Their husbands had confidence that they could take over these estates.

Yael: They were hugely competent, smart women. And Dona Gracia living in Constantinople was in fact so well connected that she even had direct lines to the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, which we’ll come back to a little bit later.

So in the wake of this burning at the stake, Dona Gracia who really is a hugely interesting woman, and I wish we had time to get into her whole biography, she, um, she had many different names. She was given a Catholic name which she hated, and insisted on being called Gracia which we believe she chose as a translation of her Hebrew name Chana, from the root chen, which means grace in Hebrew. She had a very strong Jewish identity. And even though she had been forced to live as a converso for a time in her life, she never deviated from her commitment to Judaism. Um, her husband, the one who left her the money was actually her uncle which was very, very normal at the time, not casting any judgment. Um, and not only was-

Schwab: Was this way when, you know, when the money passed to her, it was still staying in the family to-

Yael: Correct. Not only was it super normal for everyone, I think, at this time in history. It was particularly common in converso families because they were concerned about maintaining their ties to their Jewish lineage and their familial heritage. They really kept-

Schwab: You wanna marry people with like a cultural similarities. You want other Jews pretending to live as Christians. The Jews living as Jews aren’t gonna fit, and the Christians living as Christians aren’t gonna fit. So there’s a smaller dating pool.

Yael: Yes. That’s generally what happened in converso communities. In bet- You know, she was very close to her family, obviously, very close to her Jewish heritage. And she was living in Constantinople. And she heard about what had happened in Ancona with these individuals being burned at the stake. And I think that was really the final straw for her. And she used her power-

Schwab: And those are her people, not just other Jews. But those are her people like fellow conversos people.

Yael: Yes, that is a perfect connection for you to make. Exactly. And that’s why she’s gonna take the stance that she took and Benvenida is gonna take this stance that she took. Um, so Dona Gracia uses her considerable power to send messages from Constantinople to Ancona and to Jews all over the Adriatic Sea and other places that were using Ancona as an important port that they should organize a boycott of the port of Ancona, which really took… could have taken a toll on the Italian economy, and I think did take a toll for a short time. and what’s notable about this is not only that it was a woman, Dona Gracia, who had organized it. But it was really the first time in history that we’re aware of that Jews used their economic and political power to try to protest policy that was being inflicted upon them by an oppressor.

Schwab: And people listen and participated, I assume. Like the boycott was effective ’cause people did it. Was it just other Jewish merchants in other places?

Yael: I can’t say with 100% certainty. But I do believe that it was. As I mentioned, Jews had really, um, taken up the mercantile trades in Ancona. So, their withholding their business, really did take a toll. The boycott did not last very long. And the reason why the boycott did not last very long, I think no more than a few months, is that Benvenida ultimately won out. Benvenida who also had considerable pi-

Schwab: She was the other side of this. Okay.

Yael: She was the other side. She was an Italian Jew. She had never been a converso. And she was also someone who had ascended to political and economical power, I believe through inheritance, and a very controversial inheritance, if I remember correctly. She felt that an economic boycott would do more harm than good in that it would anger the Italians. It would further anger the pope who already really didn’t like the Jews living in the Papal states. Pope Paul IV, he was the one who created the ghetto in Rome. He tried to impose a code upon the Jews where they could only dress in yellow, which to me, you know, really eerily evokes the yellow star from the Holocaust.

So he was not a good guy. And he really didn’t like the Jews. And Benvenida never having lived this half-life or quasi-secret life that Dona Gracia had lived as a converso, she didn’t want anything to further anger or annoy the pope, or the Italians.

Schwab: Yeah. I love… You said this at the beginning. But like this sounds a lot like conflicts that come up now. And there’s antisemitism or there’s antisemitism about a particular issue. You know, by focusing on it, are we going to draw the ire of all the antisemites, you know when… Everybody’s gonna hate all the Jews. And like I, I hear really both sides of it, you know.

But Benvenida, right, is the second.

Yael: Yeah. Benvenida, yes.

Schwab: Like right now, it’s just about the conversos, the crypto-Jews. But if we start this whole boycott, everyone’s gonna hate all the Jews, and then all the Jews are gonna be punished. And-

Yael: It’s definitely something that comes up a lot. Even outside the context of antisemitism in any sort of conflict, do you keep your head down and try not to be noticed, try not to further poke the bear, or do you stand up and fight? I’m not saying that what Benvenida did was at all cowardly. It’s just two totally different approaches to how to deal with persecution and conflict.

Schwab: I didn’t think you were saying it was cowardice. I think it’s, what’s our best path to preservation here, right? Do we sometimes just suffer from smaller scale persecutions but continue to live and build our communities and try to avoid a larger conflict, or, is Gracia Mendez’s point of just, look, there are things that we can’t stand. And what’s the point of all this power that we have amassed for ourselves if we’re not gonna do something with it.

Yael: So I think, you know, there are those who feel that the two women could have cooperated. And if they would have cooperated, that maybe there could have been a more successful outcome. That, to me, rings of sort of modern day misogyny of, you know, women don’t support each other.

Schwab: Yeah. (laughs) I’ve never heard any stories of any conflicts involving men. So it seems to me-

Yael: Yeah. It’s only women that get into fights like this.

Schwab: Only when women have power are their issues between them.

Yael: Correct. Correct.

Schwab: I hope that by now, the listeners have gotten my sarcasm.

Yael: You’re being sarcastic? I’m a little slow on the uptake. One thing that I neglected to mention is that it wasn’t simply that Dona Gracia thought we should boycott the port of Ancona because I think that also would have hurt Jews economically. And I don’t think she wanted to hurt everyday lay Italians economically either. Her proposal was that they move to the nearby port of Pizarro which apparently was a less desirable port for a few different reasons, one of which was that the water was not as deep and perhaps that limited what types of ships could enter that port or how many ships. And I just think it’s so interesting that something as seemingly benign as the depth of water in certain parts of the Adriatic Sea could make a difference in a political movement, um, because there were people who didn’t wanna support the boycott because they didn’t wanna use the port of Pizarro. It was less desirable from an economic perspective.

Schwab: It’s a shallow port. Come on. Yeah.

Yael: Yeah. Nobody wants a shallow port.

Schwab: No one wants to do shallow port shipping.

Yael: Exactly. Exactly.

Schwab: Do you know the kind of additional, I don’t know, manpower you need to unload your goods.

Yael: I do. I’m intimately familiar with how hard it is to load and unload a cargo ship. I’m not. It sounds really hard. But Benvenida opposed this not only because in general was she trying not to poke the bear. But she also felt that there was a tremendous amount of antisemitism in Pizarro.

Schwab: So it’s not like that port is so much better.

Yael: Yeah. There had been some major antisemitic incidents there. Um, there was a count, the count who had a lot of power in Pizarro, was not a fan of the Jews and also had done some despicable things, maybe not as viscerally despicable as burning 25 people at the stake. But I think Benvenida did not wanna reward him either.

Schwab: When you first said count, I thought you were gonna say that there… they were… They literally counted all of the Jews and then did something with that number. (laughs) But-

Yael: It’s totally possible-

Schwab: They probably did that too. (laughs)

Yael: Yeah. And going back to a question you had before about Benvenida, I’m just… was reviewing some notes here. And it does seem that she attained a lot of her economic and political power through sheer force of will and apparently that she did win that inheritance controversy really truly based on her character and her forcefulness. So we’re really talking about someone who must have really been something.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. So they’re on opposite sides of this debate. And we may not know this. But were they directly talking to each other or they’re sort of just operating in their own independent spheres?

Yael: I’m not sure what the communication was between the two of them if letters were sent or messengers were sent. But they did know each other personally from back in the day, apparently living in Italy. So it could be one of these, you know, childhood or young adult dislikes that really ended up playing out at a much larger (laughs) stage.

Schwab: They were rivals all the way back … from the school that they probably both were not allowed to attend. (laughs)

Yael: Yeah. They were like schoolyard frenemies maybe. And what happened was that, um, Benvenida’s family fled, never having converted. And Dona Gracia’s family fled to Portugal. But ultimately, all the Jews living in Portugal were forced to convert. So they came from a common place and common experience. But they took basically the two different routes that Jews coming from the Iberian Peninsula could take at that time.

And ultimately that deviation from the common path led to two totally different takes on what should be done to address the persecution of Jews, um, in Ancona where, you know, neither one of them was living. Certainly, Dona Gracia wasn’t living there. I don’t think Benvenida was either.

Schwab: It, it really seems to me like somebody should make a great Hamilton-style musical about these two women, and their rise to power, and like their differing views of things.

Yael: Yeah. I think they were both really powerhouses. And I haven’t gotten into a lot of detail here about, you know, other ways in which they exerted influence. Dona Gracia, um, had the Ottoman sultan send a messenger to Ancona to deliver a message to, I don’t know if it was the pope himself who probably wasn’t in Ancona, but maybe his surrogates that the Ottoman empire would potentially take military action if the Jews were not left alone or at least treated slightly better than they had been treated which to me is mind-blowing. That is a mind-blowing piece of information that this woman, or maybe this woman as a representative of a powerful Jewish community in Constantinople, had the wherewithal to get the Ottoman sultan to threaten military action.

Schwab: Like how did this all end? So the boycott didn’t last?

Yael: Benvenida won out. Their boycott ended. And Jews continued to be treated pretty shabbily in Italy.

Schwab: Yeah. And Jews were persecuted more.

Yael: They were persecuted significantly further. I’m not… probably not giving any of this information in order. But, uh, Italian cities continue to be ghettoized. I think the ghetto in Rome was first. But there were subsequent ghettos in Venice.

Schwab: That’s, that’s the original ghetto, right? Ghettos is an Italian word.

Yael: It’s an Italian word, yes. It was difficult certainly for Jews living in the Papal States for a significant amount of time thereafter. So it ended, um, not with a bang. But-

Schwab: (laughs) with the whimpers of thousands of Jews.

Yael: Yes. And, European Jewish history continued to play out for several more centuries, with certainly subpar and, sometimes, really abominable treatment of Jews in many countries.

Schwab: But somehow these two women have sort of faded to the background a little bit. I’m glad we’re talking about them. But like why is it that they’re not-

Yael: Not better known.

Schwab: Not better known. Not bigger characters.

Yael: It’s a great question. I’m sure that like many people, both men and women, their heroic acts or at least their attempts to change the fates of the Jewish people have faded into history, and are only known by those who really seek out the details which is why I’m really glad that we’re talking about it. But it also definitely leads me to wonder how many other women and men, but most, you know, women-

Schwab: Right. And up to now, most of our characters that, that we’ve talked about in other episodes have been men.

Yael: Yes. And I think We will likely pivot back to that (laughing) in the next episode.

Schwab: A couple, couple more episodes on famous men.

Yael: Maybe I’ll dig into this a little bit. We can get back to some heroic women in Jewish history. Something really interesting to think about here is how we use our economic and political power today to uplift both Jews and non-Jews in the world who are suffering. We often talk about not buying this brand or not buying that brand because of a political stance that they take or a spokesman that they have, or where they are willing to do business and where they’re not willing to do business, not gonna name any names. This is something that plays out in our day-to-day lives probably a lot more than any of the other topics that we talk about. I tend to take these things on a case-by-case basis and often feel conflicted, often do not have the fortitude to not buy a product that I’ve come to rely on or really like or think is the highest quality or the cheapest if you know me, that’s probably the case. You know, these are, these are things that come up. And I can’t say that I would pass any sort of purity test, in terms of my actions in that sphere. Maybe, it’s something to think about a little more closely for me.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Wow. Thank you for unburdening yourself, Yael. I, I think-

Yael : Guys, I am sharing with you so much.

Schwab: (laughs) Uh, to me, it feels like there is something very Jewish sort of culturally about the idea you’re talking about. If, if one of our leaders or part of our community organizes and says, “This is a thing we shouldn’t support or this is a thing we should boycott,” there’s a feeling of obligation or guilt sometimes possibly of, “we should be following this. We should all be doing what this person or what this group is saying of boycotting, or not supporting, or supporting things that do seem like they’re pro-Jewish. Sometimes, I wonder, like, does that exist in other cultures? Are other cultures, you know, or religions or groups like as organized about saying, “Let’s all no longer buy these shoes.”?

Yael: I would imagine that every group has their own issues and their own problems that they feel the need to deal with, whether it’s being persecuted, um, or whether it’s not being celebrated in the way that they should be celebrated. I know that. Um, I believe there’s some sort of controversy now. I can’t remember where it is about, um, whether or not public schools will have off on Diwali.

And I believe that in order to not give a day off on Diwali, certain districts have now decided that they’re not gonna give a day off on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur because if they do that, then, they have to do Diwali as well.

Schwab: What? You’re gonna start celebrating everybody’s holidays?

Yael: Exactly.

Schwab: We can’t do that.

Yael: And, and so, I’m assuming that in communities where something like that is important. Um, that’s just one example that there is political action that’s taken and people organize, I would hope. I’m sure that there is. And so, I don’t think it’s uniquely Jewish. But, um, it’s definitely something that has come up over and over again in our history.