In 610 CE, after years of tortuous oppression by the Byzantine Christians, the Jews of the Arabian Peninsula were living in relative safety as respected craftsmen, metal workers and jewelers. At the same time, in a cave near Mecca, Muhammad, the founder of Islam, claimed he had received revelatory visions. Visions that indirectly would impact Jewish life, for better and for worse, forever.

Muhammad ibn Abdullah was born in 570 in the Arabian town of Mecca. He had a difficult childhood. His father died before he was born, and he lost his mother when he was only six so he was ultimately raised by an uncle, a merchant who taught Muhammad many tricks of the trade. Muhammad learned quickly, and by the time he was a teenager, he had earned the nickname: “El Amin—the one you can trust.” As he grew older, Muhammad became aware of the moral deficiency of his fellow Meccans; they worshipped idols, neglected women and the poor, and were materialistic. He was increasingly disturbed by this reality and began to spend more and more time alone, meditating and fasting. According to Muslim tradition, it was during this period that Muhammad received a life-changing revelation in the form of the angel Gabriel. Gabriel commanded Mohammad to spread the belief in one God, or Allah, in Arabic, and recite divine verses that would eventually be included in the Qur’an, Islam’s central religious text.

Three years later, Muhammad set out to share his vision. But, while the minority Jews and Christians believed in a singular God, most of the surrounding Arabs were polytheists and did not. This didn’t deter Muhammad, however. In the beginning, he managed to convert around 40 people in spite of opposition from the merchants of Mecca who’s trade depended on the city’s pagan rites and religious sites. In 622, an assassination threat forced Muhammad and his small band of followers, known as the “Companions” or “Believers”, to flee to Medina, a city almost 300 miles away.

The people of Medina responded more favorably to Muhammad’s message, perhaps because of their contact with the many monotheistic Jewish tribes who had lived in the region for generations. Muhammad believed in the same attributes of God that the Jews did and even adopted many Jewish customs. He and his followers prayed toward Jerusalem, fasted on the Jewish day of atonement, and adhered to dietary laws that shared striking resemblance to Judaism’s dietary laws, Kashrut. He also adopted the Jewish ritual of circumcision. Mohammad assumed that because of these similarities, the Jews would look favorably upon Islam and be willing converts, but he was wrong.

The Jews put up a strong resistance to Mohammad’s claims of prophecy. For starters, Mohammad claimed to be a prophet centuries after the end of the Jewish era of prophecy. Malachi, the last Jewish prophet had died some 1,000 years earlier, and according to Jewish tradition, the seal of prophecy was only to be reopened when the Jews were able to return to their spiritual center of Jerusalem, at the end of days. It was also unacceptable to the Jews that Muhammad viewed Jesus as a prophet. In addition to conflicting religious beliefs, the Jews were concerned that, like Jesus, Muhammad would be deified, and they would once again experience terrible persecution.

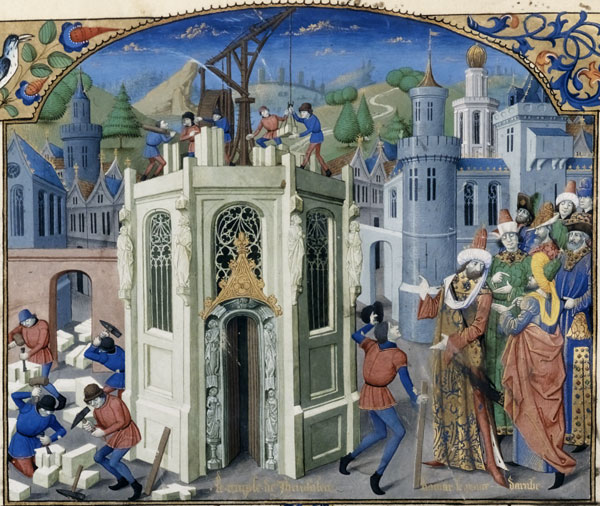

As time went on, relations devolved further. Muhammad and his believers levied accusations of treachery against the Jews, and they fought and massacred many. When they laid siege on the forts of the Jewish tribe of Banu Qurayza, all of the men were beheaded, and the woman and children enslaved. Who survived? The few who agreed to convert. Muhammad reportedly said, “Had [only] ten Jews (or ten rabbis) followed me, every single Jew on earth would have followed me.”

In 628, Muhammad’s now 700 followers attacked Khaibar, the largest Jewish community of the Arabian Peninsula and burned down their date palm groves, destroying their main source of livelihood. The Jews were then forced to surrender and give up 50% of their harvest as a form of taxation. This tax, known as the jizya tax, was a means of humiliation and discrimination that would endure for centuries in Islamic law.

After his death, Muhammad’s followers continued to conquer the Middle East both militarily and ideologically. Within ten years, they conquered the Land of Israel (then known as Palestine), Syria, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Persia. They advanced across North Africa, and in 711, conquered Spain. By the middle of the 8th century, 90% of the world’s Jews were living under Muslim rule.

In Islam, the Jews had a new adversary, but no generalizations can be made about Jewish life under Islamic rule. It was as varied as the rulers that reigned. Although Jews were allowed to practice their religion, they were always treated legally as second class citizens, officially designated dhimmi status, and subject to strict rules. If the Jews kept their heads down and paid the heavy annual tax, they could generally live without fear of forced conversion, massacre, or expulsion. And while the system occasionally broke down, this relative freedom enabled a flourishing of Jewish thought and set the stage for some of Judaism’s most influential essential scholars and philosophers.