By the 12th century, after a period of relative harmony under Muslim rule, the Jews of Spain once again faced terrible persecution. Nevertheless, Sephardic Jews produced one of the greatest Jewish scholars of all time. Today, he is almost universally revered, but in his time, great controversy surrounded the one who would come to be known as – Rambam.

When Muslim rule arrived to Spain in 755, the Jews welcomed liberation from a hostile Christian society. While far from perfect, life under Islam as dhimmi, second-class citizens, was generally better than it had been under Christian rule. By the 12th century, Jews had joined the greater society as doctors, financiers, diplomats, and poets. In their own communities, Jewish writings and scholarship flourished.

In 1138, amidst this flourishing, Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, commonly known as Maimonides or by the acronym Rambam was born. He was raised in a prosperous, educated Jewish family. At an early age, Rambam was taught by Torah masters and soared through his studies. He even began to teach others and formed a strong bond with his first student: his younger brother, David. Sadly, in 1148, when Rambam was 10 years old, everything changed. The Almohad, a North African Muslim empire, conquered Córdoba—forcing Jewish families to choose conversion, expulsion, or death.

So, his family moved… several times… First around Southern Spain, then to Morocco when he was 24… until they eventually landed in Egypt in 1168. For a brief period, life seemed to settle down until Rambam’s brother David, on a routine expedition to India in search of wealth, died, lost at sea. When Rambam heard the news, he became physically ill and could not leave his bed for an entire year. In a letter, he wrote:

“The greatest misfortune that has befallen me during my entire life—worse than anything else—was the demise of the saint… And how should I console myself? He grew up on my knees, he was my brother, he was my student.”

And, as if grief wasn’t enough, Rambam and his family had come to rely heavily on his younger brother for financial support and they now had no income. Though the Rambam’s rabbinical scholarship had grown, the rabbinate of the time was considered a public service and Rambam did not wish to receive financial support from the community. So, Rambam did what any reasonable Jew would do… he became a doctor. As a practicing physician, Rambam wrote medical theories, chronicling contemporary conditions like asthma, diabetes, hepatitis, and pneumonia. He even stated the importance of eating in moderation, living an active lifestyle, and balancing mental health.

But it’s Rambam’s contributions to religion that were even more remarkable. Following in the footsteps of Saadia Gaon, Rambam was a voracious reader who’s unique mind plumbed the depths of Jewish theology, alongside Islamic and Greek philosophy.

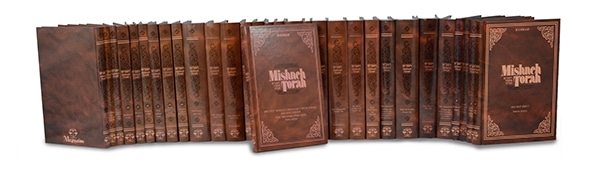

Rambam’s ground-breaking work, the Mishneh Torah, was an all-inclusive guide to the complex system of Jewish Law. Even now, 800 years later, Rambam’s reorganization of the Talmud’s 2,711 dense pages of Jewish thought into fourteen thematically arranged sections in the Mishneh Torah is still unmatched in breadth and lucidity.

But the Mishneh Torah didn’t persuade everyone to follow Rambam’s teachings. Several critics complained that he didn’t cite his sources, some were upset that Rambam reordered topics in the Talmud, and others were concerned over Rambam’s lack of transparency in arriving at his final conclusions. But, Rambam was unphased. In a letter to his student Rabbi Yoseph ben Ha-Rav Yehudah, he wrote of his Mishneh Torah:

“In future generations, when jealousy and the lust for power will disappear, all of Israel will subsist on it [VISUAL: MISHNEH TORAH] alone, and will abandon all else besides it without a doubt.”

Rambam complained often of his critics—how they robbed him of his peace and the ability to devote himself to his Torah study. Another of Rambam’s theological works, The Guide for the Perplexed, reconciled Jewish theology with Aristotelian philosophy. It was even banned in some Rabbinic circles. Some dissenters felt that Rambam’s work more closely resembled the words of Aristotle than those of Moses.

But none of the criticism deterred Rambam from writing seven Judaic and philosophical works, over a dozen medical works, and his Treatise on Logic. Some scholars claim that Rambam’s incessant work ethic finally led to his untimely death in 1204 at the age of 66.

Today, tens of thousands of students still study Rambam’s work everyday—and you can see his legacy in modern medicine. Ideas surrounding current sanitation standards, contemporary research methods, and present-day hospital planning can all be found in Rambam’s teachings. His most lasting medical influence, according to Dr. Beni Gesundheit, was that, “[…] a physician should treat his patients with optimism, joy and utmost kindness.”

How did Rambam manage it all? One answer may be his belief that we should learn as much as we possibly can and then… keep learning. “Your purpose,” he wrote in The Guide for the Perplexed, “should always be to know… the whole that was intended to be known.” Rambam’s tombstone still stands in the Holy Land today and is inscribed with this message:

“From Moses to Moses, there never rose another like Moses.”