“If America and Israel ever went to war—whose side would YOU be on?”

That’s a question that has been batted around by American Jewish children for decades.

And while it’s often posed in a playful tone, it speaks to a real question at the heart of the American Jewish experience: Is it possible to be a great American and a great Zionist, at the same time? Or does an American’s support for Israel automatically trigger an issue of dual-loyalty?

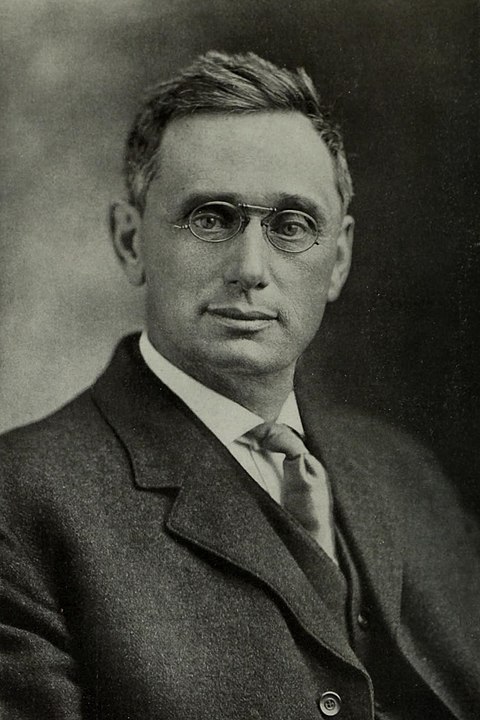

Well, that’s a question that America’s “super-lawyer” Louis Brandeis faced in 1914. He really wanted to get appointed to the Supreme Court — and he had the credentials. He was a crusading progressive known as “the people’s lawyer,” famous for graduating Harvard Law School with the highest GPA in its history, and was close friends with the new president of the United States, Woodrow Wilson. But as a Jew, Louis was being asked to lead the American Zionist movement which was trying to establish a Jewish homeland in the far away land of Israel, then known as Palestine.

Would such a position doom his political career? Would people doubt his loyalty to America? After all, the U.S. at that time was much less tolerant of Jews than America is today. And most Jews believed that to get ahead it was best to be an American publicly while keeping your Jewish identity private.

Louis decided, he didn’t care – he would follow his conscience. Besides – he saw no contradiction. He insisted that being a proud Jew made him a better American – just as his Zionism reinforced his liberalism and his Americanism.

But Louis wasn’t always a Zionist, let alone a proud Jew. Louis was born in Louisville, Kentucky in 1856, the son of immigrants from German-speaking Bohemia. He grew up in a very assimilated household, learning much more about his German cultural roots than his Jewish background. He often had a Christmas tree in the house.

Raised as an Abraham-Lincoln-loving abolitionist, he made his way to Harvard Law School – graduating first in his class at the ripe old age of 20. Over the next few decades, he built his fame and fortune as a progressive lawyer.

Progressives at the time looked at society as a laboratory, tinkering constantly with America’s most pressing social and economic problems. They believed if you could make just the right changes, you could get just the right results. As a leading reformer, Brandeis was often on the front lines fighting against poverty and injustice — while championing equality and workers’ rights.

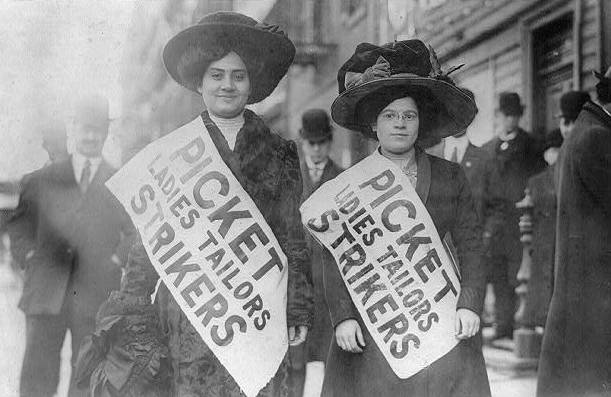

In 1910, when he was 54 years old, Louis was called in as the mediator trying to end the New York garment workers’ strike. Watching the mostly-Jewish workers struggle with their mostly-Jewish bosses changed his life. Louis was impressed that both sides actually listened to one another and bothered understanding the other side’s arguments.

And hearing the Jewish workers describe their struggle as part of a broader liberal fight for workers’ rights – he was impressed that their Jewish heritage opened their eyes and their hearts to others, rather than shutting them down.

Around this time, Louis heard about another prominent assimilated Jew, Theodor Herzl, who had his own Jewish wake-up call. Theodor Herzl lived in Europe and in the 1890s responded to growing antisemitism and assimilation by calling for a Jewish State.

Louis was fascinated by Herzl’s conclusion that the Jews needed to return to their own land, just like all the other peoples who at the time were rediscovering their roots and expressing themselves collectively and nationally.

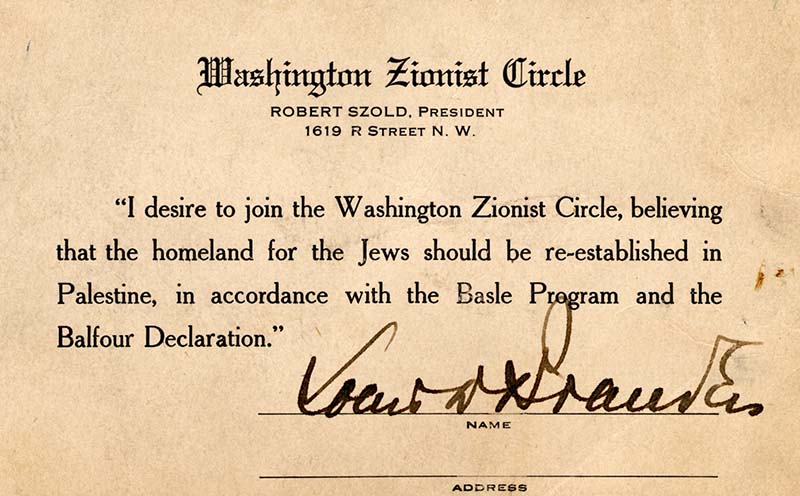

Surprisingly, Louis Brandeis found resonance with the Zionist movement, the movement to solve the Jewish “problem” by freeing the poor, oppressed Jews of the world to live in their own homeland, the Land of Israel.

“The great quality of the Jews is that they have been able to dream through all the long and dreary centuries,” Louis realized.

At last, Zionism – meaning Jewish nationalism — would give the Jews “the power to realize their dreams,” by establishing a Jewish homeland in the region known at the time as British Palestine.

Now Brandeis had no interest in moving to the Land of Israel – American Jews had their own Promised Land and did not need a refuge. But Louis – and many other American Jews – saw no contradiction between being proud Americans and vocal proponents for the Jewish State.

American Zionists felt a strong sense of responsibility to create a refuge for fellow Jews suffering around the world including Poland, Russia, and in Palestine.

But it wasn’t that easy. Brandeis’ close friend and soon-to-be president, Woodrow Wilson, not only didn’t get Zionism, but couldn’t understand why any immigrant wouldn’t want to become 100% American. Wilson believed that, “A man who thinks of himself as belonging to a particular national group in America has not yet become an American.”

In addition, 300 leading American Reform rabbis, fearing they might be seen as disloyal Americans, would lobby Wilson not to support a Jewish national home.

However, Brandeis defied such pressures. And his conversion was just in time – historically. The outbreak of World War I threatened millions of Jews caught in this great clash. The Zionist movement – based in Berlin – now looked to its American branch to take the lead.

And that is why, even as he dreamed of a Supreme Court spot – or maybe a prized cabinet job – Louis D. Brandeis found himself in the unlikely position of debating whether or not to head the Federation of American Zionists in 1914.

As he thought through the request, Louis also had to rethink his understanding of Americanism, Judaism, and Zionism. To him, his choice was clear.

He understood that those eternal blue-and-white Zionist dreams that kept Jews going for centuries were also red-white-and-blue dreams of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness – be it as proud American Jewish citizens helping their brothers and sisters around the world or as proud pioneers in the Land of Israel, rebuilding the Jewish homeland.

“Let no American imagine that Zionism is inconsistent with Patriotism,” Brandeis insisted.

You are a better citizen and a better person, if you take care of your own people as well as your country, he taught. And like all other immigrants, only by being stronger, prouder, freer individually and in their community, could Jews contribute all that Jewish civilization taught to the great American experiment.

It really was a two-way street. The American Zionist movement became the great training ground for American Jews. As they became more involved with Zionism, once-passive, cautious American Jews learned how to do politics, advocating for themselves more effectively as Jews and as Americans.

Understanding that everyone juggles all kinds of loyalties, Brandeis explained his expansive, generous, philosophy:

“Every Irish American who contributed toward advancing home rule was a better man and a better American for the sacrifice he made. Every American Jew who aids in advancing the Jewish settlement in Palestine, though he feels that neither he nor his descendants will ever live there, will likewise be a better man and a better American for doing so…”

Under Brandeis – and under pressure as the War worsened – the American Zionist movement grew, increasing its membership twenty-fold in five years.

American Zionists were raising millions. And more and more Americans, both Jews and non-Jews, saw Zionism as the best way for helping oppressed Jews around the world – while mobilizing and inspiring Jews, wherever they lived, whatever their circumstances.

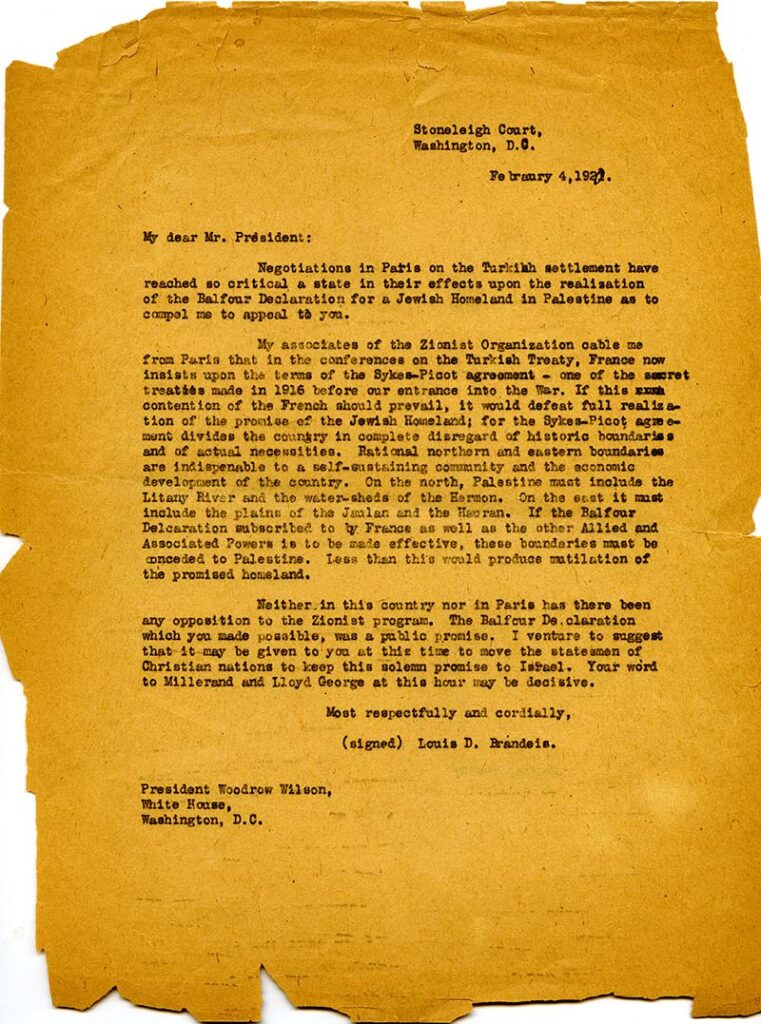

Even President Wilson turned around, relying on his friend Brandeis to be America’s emissary to this rapidly expanding movement.

Louis Brandeis’ Jewish pride reinforced his American pride

While still leading his people, he was nominated to the United States Supreme Court, becoming the first Jewish Supreme Court Justice – and sitting on the Court from 1916 to 1939.

Years later, President Franklin D. Roosevelt would nickname Louis “Isaiah,” treating Justice Brandeis as a modern day prophet.

Today, Louis Brandeis is probably the only person in history who has both a major American university named after him, as well as a still-thriving kibbutz in Northern Israel. Those two institutions reflect the all-American and deeply Jewish message his life conveys: We live today in an either-or world, with people constantly feeling bullied into choosing one extreme or another.

Justice Louis Brandeis taught us that more is more – by adding commitments, juggling ties, navigating sometimes conflicting feelings, he traded the easy path for the necessary one — and his legacy encourages future generations to do the same.