This week is something of an anniversary episode. No, not the anniversary of this podcast, though, sadly, we didn’t celebrate — we’ll have to go double hard next year.

No, this week is something much more personal: It’s my bar mitzvah anniversary! You can guess how many years ago.

But just like now, it was a weekend in early June and the Torah portion was Bamidbar, the opening portion of the book of Numbers.

Family and friends came from all over to our home in Ann Arbor to celebrate.

I’m the youngest of three boys, so I had looked forward to my bar mitzvah for a long time.

I grew up going to synagogue and I was a born performer, so I was excited to be the center of attention, leading services and giving a speech.

(And if you’re waiting for me to talk about my bar mitzvah party, I’m afraid I might disappoint you: No hype dancers, no personalized bags of M&Ms, no sweatshirts emblazoned with “I survived Josh’s bar mitzvah!” It was an open house on that shabbat afternoon. Ever the on-brand Eagle Scout, I asked people to donate to tzedakah, charity, instead of giving me presents. And the few gifts I did receive were, if possible, even more on brand: among them, my own subscription to the Sunday New York Times.)

The biggest challenge in the months leading up to my bar mitzvah wasn’t chanting the Torah or leading services. For me, those weren’t so hard.

(That could have been an early indication of my future career path.) What was hardest was writing a speech, a dvar Torah. Even though today I love writing and do a lot of it, when I was twelve years old it didn’t come as naturally. (Okay, so maybe I wasn’t always this on-brand.)

I remember that one of the most helpful pieces of advice I got was from one of my childhood rabbis, Rob Dobrusin.

Rabbi Dobrusin explained to me that a dvar torah, the kind of speech you give at your bar mitzvah, is about making connections — between one part of Torah and another, and between the Torah and the rest of our lives.

If you can find those connections, you can write a dvar Torah.

Many years later, I think Rabbi Dobrusin nailed it with that explanation. That’s exactly what a dvar Torah is: something that helps us make those connections.

You’ll recognize it immediately if you’re a regular listener to this show, or if you subscribe to my Friday emails (you can sign up at JewishSpirituality.org).

Most often I start with a story from real life–something relatable, something that helps you connect immediately and say, “Oh yeah, something like that happened to me once!”

And then I’ll draw the connection to an idea in the Torah — and hopefully you say, “Oh, I hadn’t thought of it that way!” or “Dude… Torah. That’s awesome.”

I’d add to Rabbi Dobrusin’s observation one more thing, which is that a dvar Torah isn’t just a speech or a piece of writing, but also a way of looking at the world.

It’s about living with a kind of consciousness that things are connected, that Torah always has something to say.

Paraphrasing the great Torah commentator Rashi on the very first words of the Torah, it’s almost like the words themselves are begging us, “Interpret me! Connect me to other things! Make me come alive!”

One of the greatest gifts of Jewish life is that we get to find and make those connections.

And so we could even say that to be a Jew is to have the enormous privilege of living our lives this way: not just when we have to make a speech in a pre-pubescent voice, but all the time: when we’re sitting in our homes, when we’re walking on the street.

The Jewish calendar has many rules, and one of them is that we always read Bamidbar just before the holiday of Shavuot, the holiday that commemorates the giving of the Torah on Mount Sinai.

True to form, there are many divrei Torah, explanations for why this is the case. The word Bamidbar literally means “in the wilderness,” and it describes the state of the Israelites during this whole book: in their wilderness journey between Egypt and the promised land.

So to answer the question, why do we always read this Torah portion before Shavuot, some rabbis say that the lesson here is that, just like things in the wilderness are ownerless and available to everyone, Torah too is free and available to everyone, and we want to remember that before Shavuot — all of us have equal rights and access to it.

Others take the same word and interpret it differently: Just as things in the wilderness are ownerless and free, we have to make ourselves ownerless, free, and open to what the Torah has to say if we’re really going to receive its gifts.

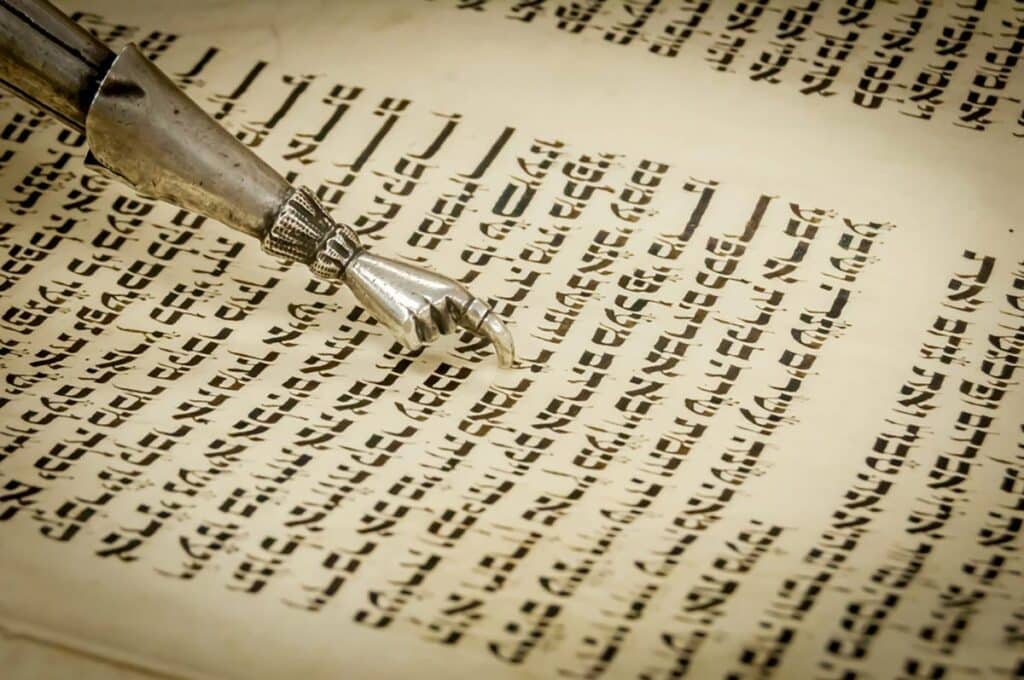

I like both of these interpretations because they reflect a deep truth: Torah — not just the five books of Moses, but the centuries upon centuries of interpretation and intergenerational conversation since them — all of that Torah is Judaism’s greatest treasure, our people’s great inheritance.

Today, it’s more accessible and available to us than it has ever been before–with so many great books and websites and podcasts, many ways to connect with other people in conversation about Torah.

We are living in a golden age of Torah, and we can come and partake of it, whether we’ve studied in yeshiva for 15 years, or wouldn’t recognize the Hebrew alphabet.

In order to do that, though, I think we first have to enter into this idea that Torah is always speaking and that our role, if we want to take it, is to listen for its voice.

Because just like we’re living in a golden age when it comes to the availability of Torah, we’re also living in the dark ages when it comes to how much noise there is in our lives.

The challenge is to find the signal in that noise, to set aside all the competing voices and to tune into the voices that matter most.

So this Shavuot, I want to invite you to make some time to cultivate this “dvar Torah consciousness.” Spend some time with a good book about Torah (yes, I have one — you can google it; there are many others that are even better).

Think about an issue in your own life or in an important relationship and spend some time finding connections to that issue in Jewish tradition (again, google can be your friend here).

Maybe find a local synagogue or an online community that’s gathering for some study over Shavuot and consider joining them for a little while.

Or, perhaps best of all, make time with a trusted friend where you can study Torah together, as a havruta or study pair.

When you read or study, use your mindfulness practice. Take a few minutes before you study to sit and be quiet, allowing your mind to settle.

Let yourself be open like the wilderness — no preconceptions, no noise, just some quiet space to tune into the voice of Torah.

Many rabbis will say that Torah study is a lot like prayer. It can just be recited in a way where we don’t really bring our full selves to it.

Or we can allow ourselves to quiet down and soften up so that we can go slowly and really be in the experience. Try to bring that kind of awareness to your study, and see what happens as a result.

What I find is that, if my havruta and I have really taken the time to be open, Torah has a way of speaking to and through us that’s just kind of amazing.

For so many people, age 12 or 13 was when their Jewish education kind of stalled or even stopped altogether.

But the beauty of Torah is that it’s available to us all the time, waiting for us to find it and make it meaningful in our own way, to connect it to our own lives.

That’s the journey I’ve been on since my bar mitzvah — and, since you’re listening, I’m so glad to know you’re on it too.