Schwab: There was a greater king and a lesser king, and there was some sort of very complicated ritual where they strangled the king. And then, at the last moment, right when the king is running out of breath, that’s when the king says how many years he’s gonna rule. Which, we’re happen to be recording this episode on election night, and-

Yael: I was just gonna say.

Schwab: … I just can’t help but think that would be a really interesting way to decide term limits.

Schwab: Welcome to Jewish History Unpacked, where we’ll do exactly what it sounds like, unpack awesome stories in Jewish history.

Yael: I’m Yael Steiner, and my childhood dream was to stay in school forever.

Schwab: I’m Jonathan Schwab, and I am in school forever.

Yael: So, Professor Schwab, what are you gonna teach me about today?

Schwab: (laughs) Yael, today I have the most incredible story.

Yael: Awesome.

Schwab: This is a Jewish history podcast, so we talk about Jewish history, and usually we talk about things that happened. And one of the parts of today’s story is something that happened. Uh, definitely we’re gonna talk about what exactly did happen and why there’s an obsession with a legend that, at least parts of it, almost certainly did not happen.

Yael: I think I caught some of that.

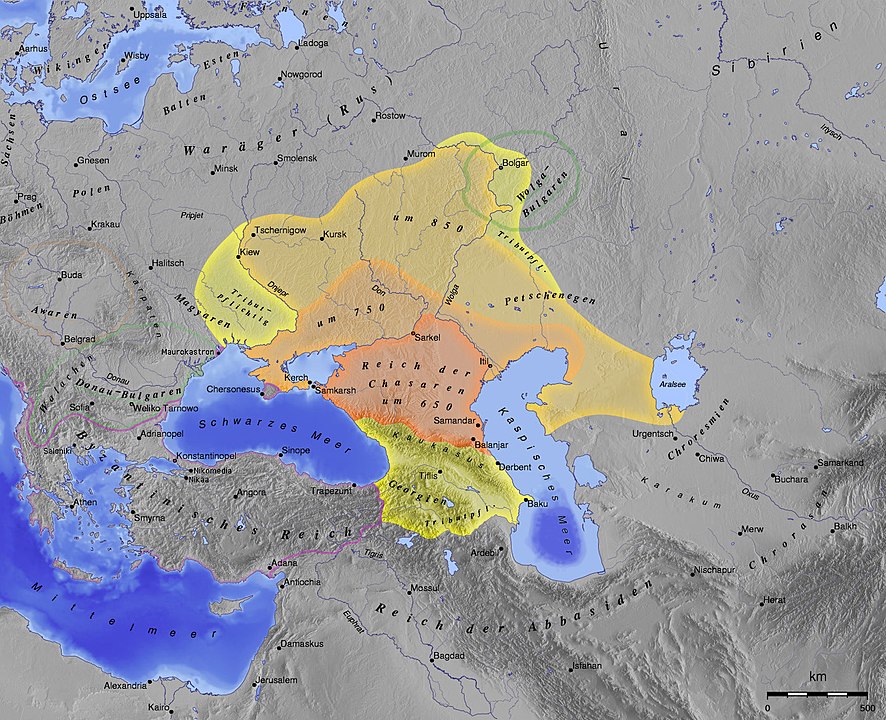

Schwab: (laughs) Before we get into all of that, what we know and don’t know, why it’s so compelling and interesting, let’s tell this legend sort of in its entirety. And it is a really compelling story. So, in the middle of the 8th century, in a region between Europe and Asia, north of the Caspian Sea, this is modern-day Ukraine, Russia, Kazakhstan, that area, if you know your map.

Yael: Totally calm geographical area of the world where nothing ever happens.

Schwab: Where nothing has happened historically or is happening today. Uh, there was, many, many years ago, uh, in the 8th century, in an empire called Khazaria, uh, sometimes pronounced Khazaria. Starts with a K-H. We’ll, we’ll do the chu pronunciation here in this episode.

Yael: Never heard of it.

Schwab: Right. Not a particularly famous one historically. And as the story goes, in the 8th century, under King Bulan, the entire Khazarian Empire converts to Judaism. And for a few hundred years, this empire continues as this sort of far-flung destination, empire of new Jews, that is encountered by passing travelers, occasionally written about in stories and histories. And then, a few hundred years later, this entire empire mysteriously and quickly disappears from the historical record.

Yael: Why have I never heard of this?

Schwab: We’ll definitely get to that. But the next question is, what happened to all of these people? Did they migrate to elsewhere? Did they become the basis for the large Jewish populations of Eastern Europe, especially Poland? Did all of these people give up Judaism for some other religion? Or, perhaps, was this entire mass conversion story overblown and this huge Jewish empire was perhaps not as big or entire as we once thought?

Yael: Who do we learn this from to begin with?

Schwab: Great question. So we’re gonna get into this whole story. One of the really important things to know is that Khazarian history, um, there’s very little of it. It’s something that we only know about from other people’s accounts and stories of it. And as we know, and has happened many times, history is very much colored by where people are coming from and what they’re writing. So, all of the other later kingdoms and empires that came after it, tell their story in a way that’s about them. And also when we say empire or kingdom, it’s a little different than the way that we typically think about empires or kingdoms. It wasn’t really organized in a more Western fashion. So this is isn’t comparable to the Roman Empire or the Greek Empire. This was spread out over a very, very large space. And a lot of the people were more nomadic.

Yael: Sounds kinda tribal.

Schwab: Right. If you’re imagining, you know, what we typically picture when we think about the hordes of Mongol warriors, it probably looked a little more like that. But we don’t know for sure, as I said, because of all the questions of the historical record.

Yael: So what you’re saying is, it’s possible these people never existed?

Schwab: We’re pretty sure these people existed. There’s definitely historical evidence for that. The question is, this whole Jewish conversion story … what happened there? There is a lot of debate on the question of this Jewish conversion, you know, this mass conversion of the whole empire. Ranging the extreme ends of the debate are, there’s nothing there, it basically didn’t happen at all and it’s a total myth. To, yeah, the whole empire did convert and this is in fact the basis for Ashkenazi Jews, and that’s where they all came from. We’ll get to that and why that particular idea still seems to be floating around today. Spoilers up at the top, uh, we’re sure that’s not the case.

Yael: Got it.

Schwab: That’s an antisemitic conspiracy theory, and we’ll get there. But that’s, that’s an idea that’s definitely still floating around. But, agreed upon historical facts, there was an empire called Khazaria, uh, we know about it from contemporary history. There almost for sure was this King Bulan character. And something did happen in the 8th century in 740. Exactly what, we don’t know for sure. And historians differ. There are historians who have different perspectives on this. There are historians whose minds have changed about this over time.

Yael: That’s refreshing.

Schwab: Yeah, it is nice. And, and one of them had a great quote, uh, in one of the lectures I listened to, where he said he had read an article, he disagreed with it, he did more and more research, and eventually came to agree with the author. So, a couple of years later, wrote a letter to the author saying, “Initially I, you know, disagreed with your idea, but now I’m writing a follow-up to say I actually think that your theory makes sense.” And this original author, wrote back to him and said, “How incredibly boring. Because I find it much more interesting when people disagree.”

Yael: Oh, academics.

Schwab: One of the things that’s interesting when we think about, you know, just, like, okay, what exactly did happen here? And, and what are the, the sources for figuring out, from a Jewish perspective, you know, how this all fits into Jewish history? There’s a lot of rabbinic literature from this time. From the 8th century to the 10th century there’s an awful lot of Jews in Europe, certainly, writing an awful lot of things, and contributing a lot to rabbinic literature, uh, writings about law, writings about history. And there’s very little mention of this Khazarian Empire of Jews. So, we can’t make, what I heard referred to as, “the argument from silence.” The fact that they’re not talked about doesn’t mean they didn’t exist, but it does bring up some questions for us. If there is an entire empire of Jews somewhere, why wouldn’t it be talked about in rabbinic writings?

Yael: I mean, that location is pretty far-flung.

Schwab: Yes, exactly. It is pretty far away. And that leads to one of the two ideas of, the fact that it was so separate from everything else and it seems like there’s very little connection, means that whatever Judaism was being practiced probably looked and felt very, very different from the Judaism that was being practiced elsewhere in Europe. And one of the explanations is that maybe the Khazarians converted, but not to rabbinic Judaism, that follows not just the, the Bible, the written Torah, but also, you know, a whole set of rabbinic literature that came later, the Talmud, uh, but to Karaite Judaism. And that they sort of just really followed the Bible and rejected everything else that came later.

Yael: Well, did they meet Jews? Did a Jew come to town and then, they decided to convert?

Schwab: You’re saying what, like, how did King Bulan decide it?

Yael: How did the seed even get planted in King Bulan’s head?

Schwab: We don’t even have time to get into this, But the whole structure of how Khazarian society works w-… There was a greater king and a lesser king, and there was some sort of very complicated ritual where they strangled the king. And then, at the last moment, right when the king is running out of breath, that’s when the king says how many years he’s gonna rule. Which, we’re happen to be recording this episode on election night, and-

Yael: I was just gonna say.

Schwab: … I just can’t help but think that would be a really interesting way to decide term limits.

Yael: This is also very much like a, if she drowns, she’s a witch kind of thing.

Schwab: Right? Yeah. “With your last breath, tell us exactly how long you’re gonna rule, you know, and then we’ll hold you to it.” Which I think they really did.

Getting back to our question of just, like, you know, what connections were there? And did anybody meet anybody? Um, and where did King Bulan get this idea? So, one of the texts that sort of frames a lot of this comes from a Jewish character named Hasdai ibn Shaprut, who lives in the 900s in Muslim Spain. And, in addition to wishing we had a whole episode just to talk about Khazarian kings, I also wish we had a whole episode just to talk about Hasdai ibn Shaprut, uh, ’cause he was a scholar, physician, diplomat, writer, very cool guy.

Yael: Interesting. Also very cool name.

Schwab: Yeah. Hasdai ibn Shaprut, like, A-level name. That guy’s killing it. So, more than a thousand years before we’re recording this podcast, Hasdai ibn Shaprut also wanted to know, “What’s the deal with this story of the Khazars and this legend?” So, he sent some messengers from Spain, all the way, hoping to get to Khazaria. They didn’t make it the whole way. They got stopped in Constantinople, modern-day Istanbul, in Turkey. But they were able to get the message through to somebody who got a message to somebody in Khazaria, who then sent a letter back. And we have this letter from the then king of Khazaria, King Joseph. Uh, and King Joseph tells the complete story of how King Bulan converted the whole empire to Judaism.

And the way he tells it is, the Khazarians are this empire, and they’re sort of between two worlds. Islam is growing in popularity, and from the south and sort of also from the east, uh, more and more kingdoms are falling under the influence of Islam. And at the same time, from the west of Khazaria, Christianity is growing in popularity and growing closer and closer. And Khazaria, up to that time, they practiced their, you know, traditional pagan religion, worshiping the ground and the thunder. Um, and King Bulan, being very practically-minded, said, “We have to find a new religion and we gotta figure out what’s gonna keep us safe long-term from all these religious wars that keep falling on our doorstep.”

Yael: So, he didn’t necessarily have some sort of divine revelation or religious awakening? This was really more of a political decision.

Schwab: Right. As we’ll get to, it was an extremely political decision.

Yael: Okay.

Schwab: As this King Joseph letter to Hasdai ibn Shaprut says, he basically talks to a representative of Islam and a representative Christianity, and asks them, you know, “Oh, if we were to convert to Christianity, how safe would we be?” “If you’re Christians, safe with the Christians.” “How do the Muslims feel about it?” “Not so great.” “How do the Muslims feel about Christians?” “Not great.” “How do the Christians feel about the Muslims?” “Not so great. But interestingly, both of these religions are sort of a little more tolerant of this third thing called Judaism.” So King Bulan is like, “Oh, all right, I’m gonna hedge my bet. Sounds like if we’re Jewish (laughs), we’re, we’re kind of safe from both of them.”

Yael: First time in history those words were ever uttered.

Schwab: Isn’t that… That’s so fascinating ’cause I feel like we talk about antisemitism a lot. Comes up in every episode, uh, for obvious reasons. And this is a very interesting one of, like, “All right, the most appealing religion, the safest thing is to be Jewish.”

Yael: Amazing.

Schwab: In 8th century far eastern Europe. So, that’s why he, he chooses Judaism, according to this account. It’s not because it’s, you know, he, he deems it to be the truest religion, it’s not ’cause of any sort of divine revelation. It’s a extremely practical, political consideration.

Yael: Really interesting.

Schwab: Yeah. But, unclear how much we should really trust this source of this, this supposed letter from King Joseph to Hasdai ibn Shaprut. Um, a lot of historians have challenged it and said, “You know what this really looks like, is a forgery. You know, there was this legend going around at this time. Obviously anybody could have picked up on this legend and then, you know, written this letter and made it appear this way. But, like, we have no way of verifying that this is actually true.” And there are a couple curious things, both in the language of this letter and things that it seems to be referring to, uh, that really make us question, you know, whether it’s… whether it’s true.

Yael: So this whole thing is 10th century fanfic?

Schwab: Yeah. Right? Like, someone, someone hears Hasdai ibn Shaprut is looking for Khazarian king, and they’re like, “All right, well, let me, you know, write to him.”

Yael: Write something, got it.

Schwab: Yeah. And, and talk up this legend. And it’s not a very long letter either. It’s not like they had to put a ton of detail in.

Yael: Wasn’t 18 pages front and back.

Schwab: No. No, no, no. Definitely not (laughs). Yeah. Um, but again, maybe there’s something there. Maybe this is, you know, retelling some sort of earlier story. Um, it does seem like that could be a really compelling reason for something to have taken place, um, for King Bulan, you know, to have initiated some sort of conversion. It’s not like there are accounts at the time saying, “Hey, this thing didn’t happen. There is no such place as Khazaria.”

Yael: Right.

Schwab: Or, “I visited Khazaria and there absolutely isn’t a single Jew there.” Um, so maybe, you know? Maybe it’s, it’s supporting that story.

Yael: So how long were these Jews alleged to exist in this mythical, mystical place, Khazaria?

Schwab: So, not long after Hasdai ibn Shaprut in the late 900s, this empire, Khazaria, ends up getting swallowed up in the conquests of the Kievan Rus’, which is the empire that later gets bigger and is claimed as the origin for both modern-day Ukraine and modern-day Russia. Um, which, I… There are tensions there between those two. Might be surprising to hear. Um, but… So this… the, the conquests of the Kievan Rus’ ends up… ends up conquering a whole bunch of areas, including Khazaria. And sort of just a lot of preexisting cultures all get erased and wrapped up into, into one new, what later becomes Russian or Ukrainian empire culture. So, unclear what happens to everything. Maybe it all gets erased. Maybe it all gets swept up. And then again, there’s that theory of, like, maybe all these Jews moved somewhere else.

Yael: Right. It could be very much like Russian Jewry in the 20th century, where a new government takes hold and no one practices Judaism for a really long time. So Judaism kinda disappears, except for the fact that we had airplanes and technology that allowed us to save those tiny remnants of Judaism so that they could be revived. But obviously that would never have been the case here.

Schwab: Right. So it’s totally possible that there was a large group of people who practiced some form of Judaism. And then, like you’re saying, it’s not like they could just hop on a plane and go somewhere else, they sort of then just became part of whatever larger culture. And they, you know, gradually over time then just became whatever, like, Eastern Orthodox Christians, um, in Russia. Which, yeah, like, that’s, that’s definitely the case and is… and is far more likely than this other theory that they all moved to Poland, and that’s where Ashkenazi Jews come from.

But before we get into that, the second really interesting source that I had heard of but did not realize the connection here at all until I had gotten into it, is a 13th century, also Spanish, rabbinic source, called the Kuzari, which is, we should clarify (laughs) immediately, not a historical work. It is clearly meant to be a, a religious text like, explaining an argument for Judaism, but the way that Judah Halevi, the author of this, sets it up is as a debate between Christianity, Islam, and Judaism. Which is, for Judah Halevi, what’s going on in Spain the 13th century.

Yael: Right.

Schwab: But he sets it up as the king of Khazaria, invites representatives from each of these three religions to make their case. And who wins out? The Jew. Uh, and that’s how the king then decides that the empire should become Jewish.

Yael: That’s really interesting because the Kuzari is a fairly well-known Jewish piece of writing.

Schwab: I had… I had not just heard of the Kuzari, I have read the Kuzari. And about midway through researching this episode, I started reading about the Kuzari and assumed that I somehow was not talking about the same book that I was familiar with. Um, but, yeah, same one that we’re talking about. The one that’s usually talked about as something that’s a justification for Judaism. But it uses this frame story of the Khazars and the Khazarian king.

Yael: It’s so int-… I mean, I’ve been taught at least pieces of the Kuzari in my formal Jewish education, never really thought about what a Kuzari is, or the root of that word or what it might be. So, to hear that it might be tied to an empire of Jews that disappeared somewhere in Central Asia, is (laughs) mildly surprising.

Schwab: Yeah. It’s interesting. But again, I don’t think it’s the intention of, of the work in any way to say, “Here’s the true history of these people.”

But that’s a helpful way, as a frame, to set up the thing that, you know, the author wanted to talk about, which is between Christianity, Islam, and Judaism, which one is the true religion?

Yael: Cool.

Schwab: Yeah. So, knowing all of this complicated background, you know, and, and what it is that we think happened or didn’t happen, the most interesting part of the story today is that this is not really something that we… that we cover a lot in Jewish history. I, I was familiar with the term maybe, but didn’t know that much about it. But this is, for people who don’t study Jewish history but pedal in antisemitic theories, the Khazars and the mass conversion is super on the top of their list of episodes in Jewish history.

Yael: So I should be expecting to read about this on Twitter any day now.

Schwab: I feel like… Yeah. When I… I- it’s already on Twitter if you know how to look. Um, but there’s this theory that the entire empire did convert to Judaism. They all eventually migrated to Poland. And that’s where Ashkenazi Jews come from, was this mass conversion from these Khazarians.

Yael: Why is that bad? We had to come to somewhere (laughs).

Schwab: Everyone comes from somewhere at some point. But, it is then often used in antisemitic (laughs) conversations as proof that Ashkenazi Jews who come from Eastern Europe, people like me and, I’m gonna assume, you… um, are not the true descendants of the Jews of the Bible. And therefore, don’t have a real connection to the land of Israel, or to being given the Torah, or to God, because we’re somehow not the actual descendants of those people.

Yael: But the Jews who are the actual descendants of those people, hypothetically, either the Sephardi Jews or some other Ashkenazi Jews, is that a tacit acknowledgement that they do have a claim to the land of Israel?

Schwab: So, it’s interesting because the people I think who, who are really holding by this theory aren’t then turning around and saying, “Well, the Sephardic Jews are the real Jews.” They’re usually pointing at some other group and saying, “Those are the actual real Jews.” So, like, this is popular among groups that that identify, like, the Black Israelites as Jews, or also among people who just say like, “Well, modern-day Israelis, like, aren’t really Jews in any way because they’re all Ashkenazi, they all came from Europe. Um, and they should all go back to Europe ’cause that’s where they’re really…” And whenever I see those sorts of things occasionally online, I’m always like, “Oh, that’s funny, you think because we were… because Jews were in Europe for a couple hundred years, that that’s where we’re from.” But I didn’t realize they’re saying, “No, that’s where you’ve actually, like, always been from. You were never-

Yael: Interesting.

Schwab: … in Israel.”

Yael: So, yeah, it would be nice if we could mitigate that argument somewhat.

Schwab: Yeah. So here’s the arguments against it, although I think that People who, who believe very strongly in antisemitic, you know, conspiracy theories, this may be shocking, aren’t always accepting of great historical evidence (laughs) that being given to them. But in a nutshell, here’s the argument, um, which to me seems pretty airtight, of how we know that’s not the case that all of these Khazarian Jews did not become the basis for Ashkenazi Judaism.

Um, first of all, Ashkenazi Jews speak Yiddish, we know where Yiddish comes from. it comes from German, and Polish, and, like, old French, and Italian, and has very, very, very few connections to any sort of Turkic language. So, the idea that people would move from Khazaria to Poland, adopt a new language that would be completely different from their previous language but would look a lot like language of people who came from a different place is-

Yael: Unlikely.

Schwab: Unlikely is an understatement. Far more likely, because it’s the case, that Yiddish developed as Jews slowly moved eastward across Europe from France, Italy, Germany, eventually winding up in, in Poland and farther east, and took the languages from the places around them, um, and incorporated that slowly into Yiddish. Uh, and many other aspects of culture as well. Like, tons of evidence that Jews picked up pieces of culture from those surrounding areas. Very little evidence that there’s any sort of culture that was picked up from anything that we identify as Khazarian, um, and that that came to be incorporated into Ashkenazi Jews. And then, and I think… I don’t know. On the one hand I’m just like, “This is the strongest argument.” On the other hand, I don’t wanna hang everything on this. I have complicated feelings about these things (laughs).

Um, but modern scientific methods, we can look at genetics and we can, like, look at different groups of Jews all around the world. We can look at Jews and groups of people who are in modern-day Khazaria, and the genetics is extremely firm o- on this thing of Ashkenazi Jews are Jews, they genetically look like Jews that mixed occasionally with some of the people from their surrounding society. And there’s very… there’s no connection at all between Jews and people who exist in that geographic area of the world. And in fact, Jews genetically resemble people from the Middle East and Palestinians more closely than, you know, people from Kazakhstan, and Ukraine, and Russia.

Yael: Right. And, and I understand why you would have mixed feelings about that because we, you know, welcome converts with open arms, and they are 100% part of the Jewish community. So, their genetics might not line up with what we consider to be the genetics of Ashkenazi or Sephardi Jews.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: And I also think that’s really interesting when you think about the Khazarians because I’m wondering what it meant to them to convert to Judaism. What did that even mean? Did they wake up in the morning and just say, “We’re Jewish now”? Because obviously, um, conversion can be a controversial topic, um, in today’s Jewish world, about what it means to convert, who, who is the gatekeeper to conversion, and what you have to do or should do, and what it means to be a Jew on a lot of levels. But, I’m just trying to think about what it would have meant in… What year was this?

Schwab: 740.

Yael: 740.

Schwab: Around.

Yael: Like, you know, they woke up one day and their king said, “Hey guys, we’re Jews.” And I’m just so curious as to culturally and in their day-to-day lives what that meant. Because it might shed some light on … what it means to be a Jew today. Like, is a Jew… being a Jew how you behave? Is being a Jew where you live? Who your political leaders are? I mean, it’s a totally-

Schwab: Mm-hmm. it’s interesting because this, you know… The genetics question I think is something that, that comes up and it is a point of dismissing this, like, bonkers antisemitic theory. But, when we think about being a Jew, all of the things you listed, but not genetics, like, not… Judaism is not a race. I don’t think of that in any way as, like, an important part of Jewish identity, is, “Who were your great, great-grandparents?” You know? And, and, “Where did they live?” Um, but it’s, we’re sometimes forced into these conversations, um, much like King Bulan in some ways, but sometimes we’re forced into a conversation about what Judaism is because of what’s going on around us.

Yael: Right. Like, our enemies put us into a situation where we need to rely on arguments that we maybe are not 100% comfortable with.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Yeah. And it’s… and it’s a fascinating sort of modern, modern, like, throwback question in some way, but, like, this connection to the land of Israel that’s somehow if… You got to have a, like, a genetic root in it to, to have an attachment to it. And I, I don’t know. I personally feel like do we really need to? What if it’s culturally incredibly important to, to Jews, do we have to somehow prove that we’re descended from people who were actually there? People who convert to Judaism are, are part of Judaism and have the same connection to Israel that all Jews have. Um, and it’s such an odd way of thinking about it, is to think that there’s, like, some sort of basis in genetics.

Yael: It’s also a really interesting rhetorical tool for antisemites to link Zionism or any claim that the Jews have to the rights or the wrongs of Jews across history … um, by saying it all does or does not stem from sort of geographical relationship.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: Not that the antisemites need more tools.

Schwab: Yeah, right. Like, that’s going to be our spinoff podcast, how (laughs) how antisemites can, can use Jewish history better. So, now that you’ve gotten a sense of this whole story that I’ve spent the past couple of weeks thinking about, what do you think about all of this, Yael?

Yael: I am going to sound a little bit nuts right now, but I think we’ve established in the past few episodes that maybe that’s accurate. Um i-

Schwab: I’m so excited to hear what you’re about to say.

Yael: It makes me a little bit sad, um, because I don’t know whether or not this empire existed. I don’t know if it matters whether or not it existed. But the notion that an entire society of Jews could disappear from the Earth and that no one will remember them, with the exception of amazing podcaster Jonathan Schwab is very sad to me. Um, and i- it makes me worried. And part, you know… Half of my brain, the half of my brain that’s always thinking about pop culture, and TV, and movies, is thinking about, you know, like, The Leftovers, or The Avengers after the snap, that people just disappeared and it’s like they were never there. And the other half of me is thinking that there was just this dilution of who they were as a people. But at the same time, maybe I’m not as worried because we don’t know what their society was like. Like, we don’t know if there was any ritual, if there was any deep soulful connection to what we see religion as today. So, maybe it’s just that, you know, one day they put a sign outside their town that said, “This town is Jewish now.”

Schwab: (laughs) “Notice to all conquerors. Christian or Muslim.”

Yael: Exactly. And then that sign fell down and it was over. And that’s not as worrisome to me as an entire population of people who had a rich Jewish life no longer being remembered.

Schwab: Wow. Can I give a slightly more optimistic or hopeful spin on the same idea?

Yael: Absolutely.

Schwab: I think it’s really amazing that we still are Jewish today, noting that so many things like that have happened. That, there are religions, and cultures, and empires that have come and gone, and yet we’re still here not just in this podcast talking about the thousands of years of Jewish history, but talking about ideas or events like this, you know, where, where this, like, passed into history and, and is barely even remembered, but is important to us because we’re so into this question of Jewish history. Um, and it’s wild to me, like, I think about this all the time, that Judaism has survived, often without even having an empire. And Jews have been conquered and been, you know, subsumed into larger cultures, but yet there’s so much that is still just part of this long chain of tradition that connects us all the way to the past.

Yael: And if we wanna go really far into the past, like, what you just said reminded me very much of Moses and the burning bush that the the burning bush didn’t disappear. It was not consumed. It was literally lit on fire, but still survived. And the Jews are kinda like that.

Schwab: yeah. Like, there are no Khazarians anymore. But, they’re still Jews. Always have been.

Yael: If there are any Khazarians out there and you’re listening to this podcast, can you please drop us a note or tweet us because I would be fascinated to be in touch with you (laughs).

Schwab: Oh boy. (laughs)… We might get some interesting feedback to that one. But I’m excited about it.

Yael: Well, this was really cool story. Um … I’m definitely gonna look into this more. And, you know, There’s this very cheesy song that I think we used to sing in Jewish summer camp about how wherever you go, there’s always someone Jewish, you’re never alone when you say (laughs) you’re a Jew. And if I were to meet a Khazarian Jew, I would feel a kinship to them. And it’s inexplicable. But it’s there. And it’s innate. And again, I don’t know if these Khazarian people practiced in any way remotely similar to the way that I practice, but there’s something about it where I just kinda wanna reach out and be like, “You’re like me.”

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Right. There’s something about being Jewish and feeling connected around the world to all sorts of people. Yeah. Well, this was great. So glad that I got to share this story with you. And I can’t wait for the next episode and for what you’re gonna bring.

Yael: I really appreciated learning about this. And, as I am every week, I’m super excited to dive into the next topic.