Schwab: Welcome to Jewish History Nerds, where we do exactly what it sounds like, nerd out on awesome stories in Jewish history.

Yael: I’m Yael Steiner and my childhood dream was to stay in school forever.

Schwab: I’m Jonathan Schwab, and I am in school forever.

Yael: Schwab, this is the first episode of season three of Jewish History Nerds. We haven’t gotten together to learn something new in a while.

Schwab: Yeah, and I’ve really missed it. And you, Yael. And all of you, dear listeners.

Yael: Aw, that’s so sweet. I’ve missed it too, and you, and Nerd Nation. Just one thing to note before we get started, we are recording this at the end of November 2023, and we’re obviously highly impacted by what’s going on in Israel right now, and it’s constantly in our thoughts.

Schwab: Yeah, I think that as a podcast about Jewish history, it’s always connected to the Jewish present, but our Jewish present right now, I think feels even more intimately connected to the Jewish past that we always discuss. And I think this episode today, that’s especially true about. So I’m excited to get into this conversation.

Yael: What are we talking about?

Schwab: We are talking about a Jew, like we usually do, a Jewish man and a historian, which I think we as Jewish history nerds will love, named Heinrich Graetz from 19th century Germany. But more than talking about him and his life, specifically his ideas of Jewish history and what Jewish history means and what it is.

Yael: So I feel as though he is someone I should have heard of and should know something about, but I have to say I don’t. So I’m excited to get into this. It reminds me a little bit of our first ever episode when we talked about Josephus, who was both a historian and a part of the story that we were telling. Is that kind of where we are here?

Schwab: Yeah, I love that comparison because I happen to be, you know, as I sometimes do listening to some of our old episodes to look at, and I think there are so many interesting parallels to our first episode of the first season where we talked about Josephus, a Jewish historian, and now opening season three with another Jewish historian. Graetz is a lot less, I think, of a real character in history as much as Josephus is.

Yael: Yeah, for whatever it’s worth, I had heard of Josephus. I had not heard of him.

Schwab: Yeah, it’s not a name that outside of academic circles, people really talk about a lot. And as I usually do in preparing episodes, was talking about this at my Shabbat meal this past week. And everybody there who were fairly well-educated Jews were either totally unfamiliar with the name or just were vaguely aware, that’s a historian of some sort.

But really, Graetz, like I said, and we’ll get into it, shaped so much of Jewish history and Jewish identity.

Yael: So what’s his deal?

Schwab: What’s his deal? So he was born in 1817 in Poznan, which was Prussia at the time. Now is modern day Poland. But was Prussia, so like, Germany ish, at the time? Born into a traditional Orthodox family at a time where that was, especially in Germany, becoming a really complicated type of thing. There was a rupture. This could be its own whole episode, but the rupture between Orthodox and Reform. And he’s sort of situated in the middle of that. He’s interested in some of the ideas of the Haskallah, of the movement towards intellectualism and reform, but he’s not-

Yael: That’s the enlightenment. Right.

Schwab: Right. But totally doesn’t want to completely, you know, I guess like go over to that side.

Yael: He’s stuck in the middle.

Schwab: He is. He is stuck in the middle and like, and he becomes connected to another person I think, who is stuck in the middle, Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, who is trying to articulate some sort of middle path of what we would now I think called Modern Orthodoxy.

Yael: Whatever that means.

Schwab: Whatever that means, yeah, and not a term that he used at the time. But Hirsch is remaining traditionally Orthodox in observance, but also engaging with a lot of what the world has to offer, what the world is newly offering to Jews. Graetz becomes very enamored of Hirsch, writes him a letter, wants to study with him. Hirsch invites Graetz not only to study with him, but actually to live with him in his home. So Graetz lives in Rabbi Hirsch’s home, for several years, learning directly from him. And as he’s doing this, he was like, is he going to become a rabbi? Is he going to become an academic? He goes more the route of academic, although the distinction I think is not as fine as, I don’t know that it’s always clear-cut nowadays, but even then definitely wasn’t.

Yael: Degree granting institutions were a little different at that time.

Schwab: Yeah, let’s talk about that for a second because, he decides to pursue university education but actually can’t get a PhD because the policy was, no PhDs for Jews at the University of Breslau where he studies. So he has to go somewhere else to get his PhD.

Yael: That’s fascinating because if you think about all of the famous academics, particularly scientists, particularly German scientists in history that were Jewish, so it’s interesting that that was a policy as late as the early 19th century.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Yeah, you’re especially right because it seems like probably a lot of Jews getting PhDs, a disproportionate number of them. But at the University of Breslau, that was one of their policies, no PhDs for Jews.

Yael: So what did he study? What was his field?

Schwab: So he studied history, but this new movement called Wissenschaft des Judentums, the science of Judaism, which is this idea of applying the critical tools of academia, this new way of looking at things, to Jewish literature and culture. And rather than just traditional rabbinical interpretation and exegesis, let’s use the tools that they use in other fields of study and use that to look at Judaism and Jewish history and literature.

Yael: So this is sort of literally social science for the first time.

Schwab: Yeah, it’s social science, right? Yeah, like really thinking about it rigorously and scientifically. Yeah. So he applies it to history, and he sets out. He has this idea pretty early on that he is going to write the encyclopedia of Jewish History.

Yael: Interesting. Good for him.

Schwab: Yeah. And, spoilers, he did, and it’s fantastic, and is majorly impactful. He starts out in 1853. He publishes the first volume, which is volume four, because he’s starting in the middle.

Yael: Fascinating. So he plans to go back and cover one through three at some point.

Schwab: Yeah. And then all the later ones. Yeah. Well, he specifically wanted to actually travel to Israel, called Palestine at the time, to do some firsthand research for himself about some of the earlier historical periods. So he didn’t want to start immediately after the destruction of the Temple. So he starts a little bit later, knowing that he would later, and he does in fact do this, travel to Israel, do that firsthand research and publish those volumes later. And he knew, okay, and I’ll also publish up to volume 10 or 11, depending on the version, that will take us basically to the present day. And that’s what he does. He writes 11 volumes of this work between 1853 and 1870. And it is called The History of the Jews, Geschichte der Juden.

Yael: Germans have the best words.

Schwab: Yeah. Oh my gosh, later we’re gonna get to some excellent German words that we have to talk about. It is encyclopedic and it covers everything. And this 11 volume work, History of the Jews, is seen as the text on this topic. And it is widely embraced by the Jewish community. Never before had there been something like this.

You mentioned Josephus before, and Josephus’s work also was called either that or something very similar.

Yael: I was just about to say, wasn’t it called History of the Jews?

Schwab: Yeah. History of the Jews. But you know what? Graetz, I think, had a lot more history to write, because he has to cover everything since Josephus.

Yael: Yeah, a lot more work.

Schwab: And a lot had happened. So it’s really widely embraced and received by the Jewish community, because this was something they did not have before. And this is part of what’s so interesting about the story of Graetz, is in the present day, we don’t think about him a lot. Because of course, we have his work and so many other ones that have come since then that are derivations and answers and copies of his work. But he really did something that at the time nobody else had done.

Yael: He was the first.

Schwab: He was the first to really try to set all of this down using a social scientific historical approach, try to tell the entire story. But also not just when we think about the way that we study and think about history now, not just chronologically, here’s every single thing that happened, but really try to tell a story through it. And say, this is the story of Jewish history and here’s how it all fits together. And it really is incredible because he does both of these things, like does this comprehensive encyclopedic work that brings together so many sources, so much information, is so vast, but also does a really great job of saying, and this is the story, like this is what Jewish history is and how this all fits together.

Yael: It’s so interesting to me that it was well received, because here he is at this crossroads of rabbinical education versus university education. And I was wondering whether or not the public would be receptive to this, because while the written word has always been extremely important to the Jewish people, this could be viewed as an improper deviation away from rabbinic texts. Like we use rabbinic texts to guide our lives, and if there’s history in them, great. And if not, not.

And that there was this welcoming of non-halachic, non-Rabbinic chronicling of what’s happening to the Jews.

Schwab: Yeah, yeah. So I want to make sure that I’m not overselling it, because the point that you’re making definitely also happened. There also was a fair degree of criticism, including his own mentor, Rabbi Samson Refael Hirsch, was critical of some of the scholarship. At points, he says he’s misusing quotes, he’s misunderstanding something, but also that Graetz went too far in explaining the historical context behind things and talking about the context from which different things emerged. And that’s maybe not appropriately respectful enough of the authority of rabbis, and things like that. So there definitely is a hesitation and a criticism around it. Although, again, publicly, it is very widely embraced as a text.

A great example of this: Graetz’s 11 volumes said History of the Jews was, at one point in Europe, the bar mitzvah gift that people got. Like, that’s what you got. You got this, you know, because as you know, every 13-year-old boy wants an 11-volume German language history of the Jewish people. But I think that really says something of, like, the way this text was seen, you know, like, up there on the shelf with the Bible and with the Talmud, like here is a defining text of what it means to be Jewish in the modern era.

Yael: Right, and as someone who’s reaching the milestone of Bar Mitzvah, who now needs to know what it means to be a full-fledged Jewish adult, now we’re saying part of that is understanding Jewish history.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: Curious if the reception of this book gave him any inroads into the university culture. If he was more accepted by the non-Jewish academics, given his accomplishment.

Schwab: So he, yeah, yes and no. The University of Breslau, which again had denied him a PhD, does later in his life make him an honorary lecturer and he is sort of accepted into that academic world. But also, and we’ll get to the criticisms within the Jewish community, but also outside the Jewish community, there are those, including one person in particular, who use this to fuel their own anti-Semitism and make Graetz out to be a true enemy of the German people.

Yae: How so?

Schwab: So we’re skipping ahead a little bit, but this gentleman by the name of Heinrich von Trichke.

Yael: Of course his name is also Heinrich.

Schwab: Yeah, his name’s also Heinrich, reviews this work and uses Graetz’s work to say, look, like this is what we’ve been telling you all along. Look how horrible the Jews are. And he says, Da Juden sind unser Unglück. The Jews are our misfortune. And uses the history to emphasize how bad it is that Germany basically has to deal with this Jewish problem. And if that sounds familiar at all to you, it’s because that later becomes a party line for Nazis.

Yael: So he’s saying that the fact that so many tragedies have befallen the Jewish people.

Schwab: Maybe that’s for a reason! You know, von Trichka, he’s not like innocently suggesting it. He’s like openly saying, like, hey, seems like a lot of bad stuff. Yeah, that they bring to every country they go to.

Yael: Yeah, it does seem to be victim blaming, to say that because a group of people has faced such woe that we need to get them out of here because they’re a social contagion.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Yeah, no, not I don’t agree with it.

Yael: Oh good, I’m so glad you clarified.

Schwab: Yeah. Yeah. All right. We have and I want to reiterate this. We are anti Nazi, like firmly anti Nazi stance on Jewish history Nerds.

Yael: There are so many things that I want to say to that, but I’m also firmly anti-Nazi.

Schwab: Yeah. But really, if there’s, you know, a summary of the way that Graetz sees all of Jewish history. It’s something along the lines of the Jews have suffered terribly at every point in their history. And yet despite this suffering they have succeeded in having major impacts on the world, on the societies around them through their intellectual and moral striving. And that actually I think is even my editorializing slightly because I think Graetz would not say they’re intellectual and moral striving but more directly say they’re intellectual and moral superiority.

Yael: Yeah, we’re, we live in a more pluralistic society, where we’re so much more enmeshed with our neighbors, we no longer feel as Graetz may have felt when he was siloed off from the rest of society.

Schwab: And I think, yeah, it also is thinking about how powerful that idea was at the time and why it was so popular. That gives so much meaning to what it means to be Jewish, but also gives meaning to suffering. If you can contextualize, wow, look at how much Jews have suffered, and wow, look at the contributions they have made despite the suffering. That, it not makes the suffering okay, but like gives a meaning to it in some way.

Yael: That’s a very optimistic way of looking at it. I think I know many people who would chart it differently. They would go back and say, what are the milestones of Jewish life? X, Y, and Z, these are our tragedies that have happened. And that’s how I’m gonna chart Jewish life chronologically. Whereas a different view would be A, B, and C, these are triumphs or redemptions. Or even just slight turns of favor that the Jews were able to actualize among a life of tragedy. And that’s how I’m gonna chart Jewish life.

Schwab: So yes, 100%. And that’s actually later historians bring up that exact point. So Salo Baron, who’s an American historian of the 20th century points out, although I criticize is probably the better word, that Graetz’s entire approach is so focused on the suffering, but you could instead focus on the triumphs and the accomplishments and a million other things. And he describes Graetz’s approach as, in English, it’s the lachrymose conception, which is great. Yeah, we’re making it easy for people to understand, so we’re using an incredibly obscure English word, which is like lachrymose means-

Yael: Teary, teary, yeah. I studied for the SATs, and it was only five years ago, right? High school was only five years ago, totally.

Schwab: Tearful, yeah, very good. Yeah, for all of our high school listeners, yeah. Yes, for all of our high school listeners, helpful for your SATs. Yeah, yeah, yeah, high school, so recently. The German term for it, which I think is so much better, is such a beautiful term. Leidens und gelernten, which is like the suffering and the learning. Suffering and scholarship, which I guess preserves the alliteration.

Yael: Which would be an amazing title for any book about Jewish history.

Schwab: Yeah, right. And that’s, and that’s what that’s I guess, like, what it comes out is like, is the way we view Jewish history as pogroms and books, you know, and like, the Jews were kicked out of this land and persecuted and slaughtered. And then a couple of famous rabbis wrote a couple of these amazing books, and then they were kicked out of the next land, that’s Jewish history. Of course, that’s Jewish history. But that framing of it, that’s Graetz. That’s the person who introduced that entire concept to thinking about Jewish history as unified in that way.

Yael: It’s certainly a very 19th century conception of Jewish life where you had Jews breaking a lot of ground in many fields, but at the same time you have a large portion of people in the world saying Jews are making inroads and that’s a problem.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Right. I guess because that’s the question. If you see it that way as that cycle of suffering and scholarship, like the Jews breaking out of that cycle, is that a good thing? Or that’s a, hey, we need to remind them what their place is and they should go back to it. Or do we reject that view entirely and say, well, there’s also 100 other ways to think about it and a lot of other things that are going on.

Yael: Yeah, it’s like most things in life. I think Jewish history is very much colored by the lens that you put on it. You can look at 20th century Jewish history as an unparalleled tragedy. Of course, there was an unparalleled tragedy, and that’s the headline you could use. Or you could look at 20th century Jewish history as an unprecedented triumph in terms of what was built from the ashes of the Holocaust. So again, it’s very much dependent on your personality.

Schwab: Yeah, that’s a good way of putting it. And all of that is after, like all of that comes after Graetz has already died even, like he’s, I think torn between, you know, how do we view it? Do we look at the suffering and the tragedy? Do we look at the positive aspects of it? And then, that only became more extreme, like you’re saying, after his time.

Yael: Did this accomplishment tear him away from his good standing in the Jewish community at all?

Schwab: So, as his work spreads more, and this is, I think, the tragedy sometimes of the people who break ground in a particular area is then everybody who comes after them, it’s easy to criticize the person who sort of like invented the field. And the people who are critical of him afterwards, I think sort of reject him a little bit to the point where there was, I don’t remember what year it was exactly, but it’s towards the end of his life. There’s a major conference on the study of history in Europe that you would think Graetz as the preeminent person, should be the keynote speaker at this conference. He’s not invited and he’s deliberately not invited because they’re like, we need to move away from a Graetzian model of things.

Yael: This is Jewish history or all history? Oh, wow.

Schwab: Yeah, yeah, Jewish history. Yeah, a whole bunch of Jewish historians saying, let’s have a conference. Let’s like, you know, do this thing. And then it’s like, oh, we don’t want to include that guy.

Yael: Without comparing writing this history of the Jews to inventing the atom bomb, I am getting Oppenheimer vibes, where you break tremendous ground and then you become a scapegoat for the rest of the movement. For anyone who barbie-heimer’d this summer, I don’t know if you did or not, but…

Schwab: I barbied but haven’t Heimer’d yet. I know. Yeah.

Yael: Well, I would recommend.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Ah, side note, I know for sure there’s a Jewish element to Oppenheimer. I want to say, that the inventor of Barbie, I think, was Jewish too. So oh, yeah. So we claim both of those. Barbenheimer is a Jewish thing.

Yael: Oh absolutely. Barbie is Jewish. Barbara Handler, Ruth Handler’s daughter, is the model for Barbie, not physically, but conceptually. And she is a Jewish woman.

Schwab: This is getting like farther afield from what we’re talking about, but she’s the model for Barbie in that like the plurry potential of you can be anything as a Jewish woman in America. You can do anything.

Yael: It’s Barbie and Hadassah. Those two organizations have really changed the landscape of Jewish women in America.

Schwab: Hadassah, by the way, just because you brought it up, I think the founder of Hadassah, Henrietta Schold, Szold? I think she’s the one who translates Graetz’s work into English.

Yael:Wow. What? That’s crazy. Wow. So his relationship with Rabbi Samson Rafael Hirsch, it sours and it’s not repairable.

Schwab: Yeah, sours later. Sours later. Yeah, Graetz is sort of like still in, still out, I think. I don’t know, looking back at him, like, oh, he like couldn’t figure out yet his place in like where this continuum of Orthodox and Conservative, which also, you know, emerges. And I’m so curious, this is a whole separate topic, but like, where he would be now, sort of like what denomination would Heinrich Graetz if he was in the 21st century?

Yael: So I do actually think I have a thought on not necessarily where Graetz would be, but it definitely reminds me somewhat of a rabbi and professor named David Weiss Halivni, who passed away about a year and a half ago, who very much lived at the intersection of Jewish scholarship and secular scholarship and grew up first in the Hasidic world, then in the very non-Hasidic, yeshivish world of Brooklyn, once he came to the United States after the Holocaust. And also like Graetz made an unusual choice of going to study at a secular university and wrote academic works about the Talmud that ultimately caused him to fracture with his community and ends up somewhere between the Orthodox, modern Orthodox and Conservative movements. He wrote a fantastic memoir called The Book and the Sword, and he talks there about how he was never able to fit anywhere and it reminds me very much of Graetz in that way.

Schwab: Yeah, Graetz, like not just a historian, but also a character who in some ways was like bigger than his present moment, like didn’t fit neatly into any sort of category because he was redefining categories. And like, he wasn’t mainly a theological or religious thinker. His life’s work was not in defining what a denomination was or anything like that. But his life work in defining what Jewish history really was, I think, a category breaking thing in some ways.

Yael: Did he stay observant? Did his practice or belief change over time?

Schwab: I don’t know about his beliefs. His practices have seemed like some changed over time, but he still was pretty what we would now call observant in a lot of his practices.

Yael: So he should in some way have demonstrated to the Jews of that time that there is a way to understand our history holistically by combining both the secular element and the Judaic element.

Schwab: Yeah, that’s what I feel like. I feel inspired by him as a person who, I don’t know, I think tries to live in two worlds at the same time and tries to bridge the space in between them. But also, and I feel like this is, I don’t know, maybe something that I become like more sure about, like thinking like, okay, but there are there are like, limits to that. Like the spaces do need to remain separate in some way and we can move in between them. But they can’t totally, for lack of a better term, assimilate one into the other.

Yael: Without trying to go too far afield into what is a very serious topic, there is a tremendous amount of discussion about Jewish life on college campuses. And I think Graetz is a great example of someone who was excluded from university life, or excluded at least from doctoral level studies, or maybe he studied with them but certainly wasn’t given the title, and still accomplished a tremendous amount and changed the face of Jewish history.

Schwab: And yeah, and still accomplished a tremendous amount, which is like, that’s his exact thesis, right? Is that despite the suffering of the Jews, the Jews strove to have an impact and contribute to society. And I think there’s a way of looking at it that’s, why do you keep wanting to be part of a club that doesn’t want you? I think you could look at Graetz and say that, like, Graetz, you’re literally by policy not allowed to get a PhD from this institution? He does get it from a different institution, but like the fact that that rule exists.

Yael: You’re not going to change them. Your presence in the club is not going to open it up to the light of Judeo-philia.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Right. Then there’s a part of me also that says, but there’s the other optimistic view of just like, what if it’s not just about the question of acceptance in society? I think that what Graetz would say was like, here are some great tools that exist. And why not use them for ourselves? Like, what if it’s not about whether they’ll give me a PhD in the end or not? What if it’s about writing a book that’s tremendously impactful for Jews? And it doesn’t matter what the reception of it outside of that community is.

Yael: Was this the status quo, maybe not Bar Mitzvah present, but the be all and end all of Jewish books for the German community until the Holocaust? Was this something that really perpetuated or was it in fashion? When did it go out of fashion?

Schwab: Yeah, I don’t know when it went out of like either did they move on to something else or it’s just there, you know, there just there just isn’t a Jewish community in the same way now. That’s why it’s no longer a common bar mitzvah gift.

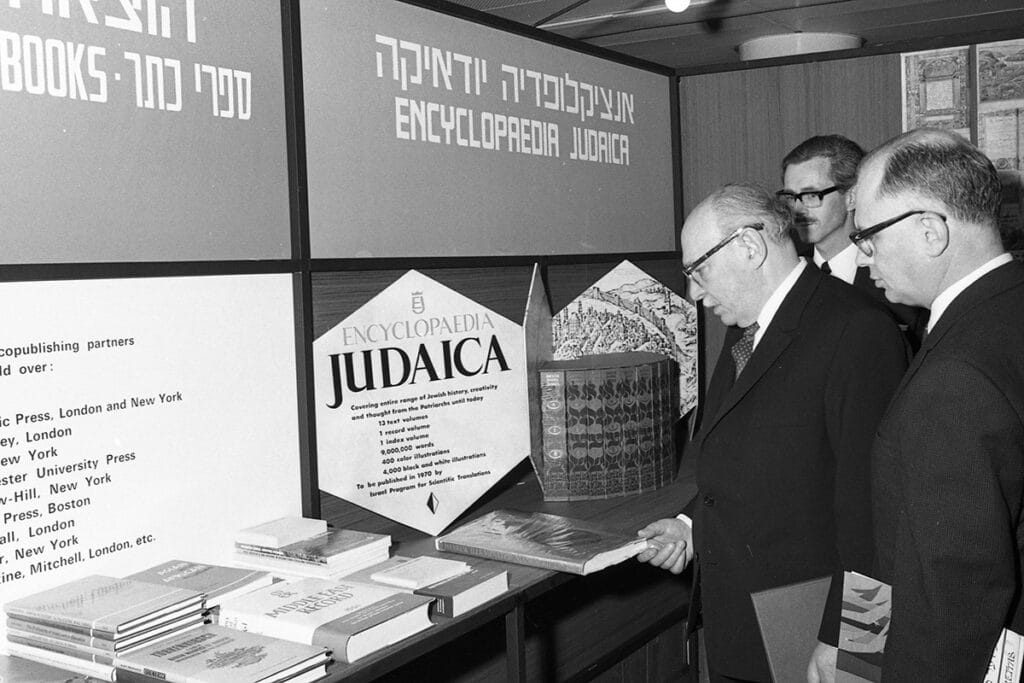

Yael: Right, exactly. But speaking of encyclopedic knowledge of Judaica, there is a set of encyclopedias known as the Encyclopedia Judaica that was first published in the 1970s and is now out of print for reasons that I think probably mostly have to do with the amount of space it takes up on your living room shelf. But being the Jewish history nerd that I am, I have always wanted a copy and I just wanna give a shout out and thank you to Debbie and Ziggy Stein, who gave me a set of Encyclopedia Judaica that they had in their home and the entire Jewish history nerd nation, thanks you for this contribution to my research and hopefully something interesting that will come out in a future podcast.

Schwab: Very cool. Did they also contribute towards buying you a bookshelf for it to fit on?

Yael: Right now it’s on top of my piano. So, so far so good.

Schwab: Nice. Well, it’s great to be back here for season three. Excited for a whole bunch of interesting stories we have this season. And even more than the past two seasons have been, I feel like it’s giving me a lot of meaning to be thinking about and studying these topics and really framing, like we said at the top, a lot of this complicated and difficult present moment.

Yael: We’re at a pivotal moment in Jewish history, certainly no question about that. And I think one of the best ways to pull ourselves out of what might be a very challenging moment personally is to feed our souls with something interesting and, you know, look at what our community has accomplished over time. And this definitely gives me the opportunity to do that.