In the 10th century, Islam was spreading, Christianity was consolidating its power, and Judaism was being torn apart from within. Judaism might never have survived if not for one man. And, chances are, you’ve never even heard of him.

Escurial Library)

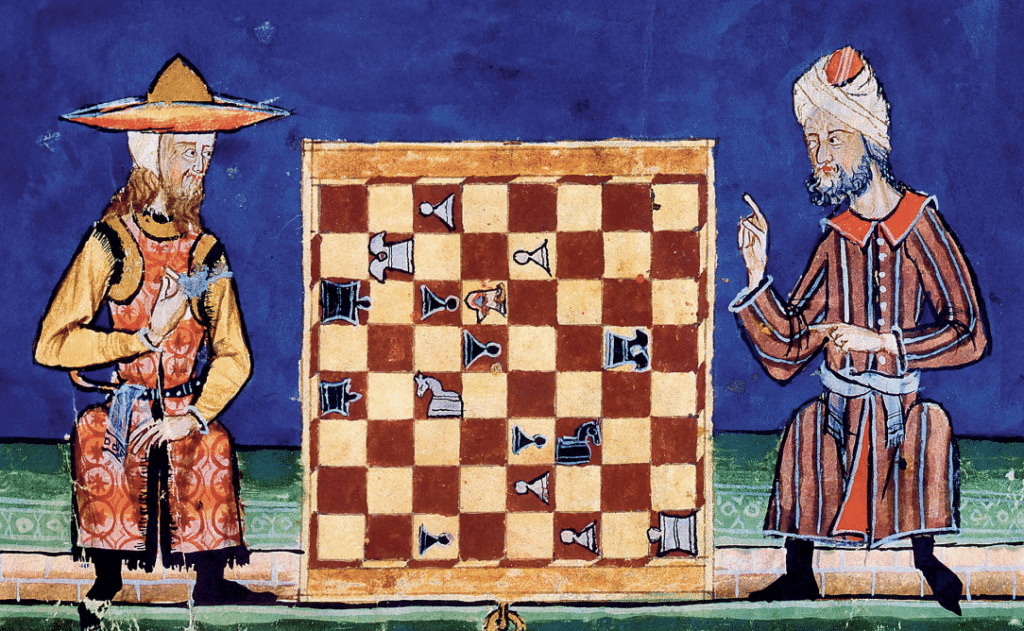

In the early Middle Ages, most Jews lived under the Caliphate, an Islamic empire that stretched from Pakistan to Spain. Judaism’s political leader the Babylonian Exilarch, David Ben ZAHkkai, reported to the Caliph. As long as the Jews paid their taxes, they could govern themselves. The Jewish Academies in Babylon thrived under this arrangement as their spiritual leaders, the Gehonim, organized the first prayer books and decided Jewish law. These leaders were so brilliant that the word Gaon, the singular form of Gehonim, has come to mean “genius” in Hebrew.

Despite their vibrance, the Jewish academies faced a major threat: a sect called the Karaites who argued that the written Torah, known as the Tanach, was all that mattered. They wanted to abolish the Torah-learning academies and scrap the entire Oral tradition, which was encoded in the Talmud. And their influence was growing.

One young man in Egypt, Saadiah ben Yosef Al-Fayyumi, joined the cause against the Karaites. A brilliant writer and deep thinker, Rabbi Saadiah never backed down from a fight. He published almost a dozen books denouncing the Karaites, deflating the movement with his deep understanding of the Torah. The Karaites fought back so fiercely that in 915 Rabbi Saadiah had to flee to Sura, the most prestigious of the Jewish Academies in Babylon.

While he was on his way to Sura, a new threat erupted. The leader of the Jewish Academy in the land of Israel, the Nasi, declared himself the leading authority by changing the Jewish calendar. If he could convince people to follow his Jewish calendar instead of the Babylonian’s, it would restore Israel’s stature and isolate the Babylonian Academies. The political leader, the Exilarch, was furious. The leaders hurled vicious letters back and forth. Nobody could agree on when to celebrate Judaism’s holy festivals, and Jewish tradition was pushed to the verge of cracking in two.

Rabbi Saadiah sprang into action. Combining tradition and innovation, he argued for the original calendar using both Rabbinic history and observational astronomy. He was so persuasive that even the Nasi gave up, ending the threat of schism entirely.

Rabbi Saadiah’s simultaneous reverence for long-standing practice and his embrace of scientific thought served him well. He was able to write the first rule book of Hebrew Grammar, translate the Bible into Arabic for the first time (a translation so good that it’s still in use today), and even create a Hebrew rhyming dictionary. His work was so influential that the Exilarch appointed him Gaon of Sura, the first Gaon ever to be born outside of Babylon. Everything was perfect… until Saadiah Gaon got in a fight with the Exilarch.

As leader of the Jews, the Exilarch judged all major legal decisions, unless a case affected him directly. But, in the year 930, the Exilarch decided the outcome of a major inheritance case in his own favor. Saadiah Gaon denounced the injustice. When the Exilarch’s son tried to threaten him into submission, Saadiah Gaon had the son thrown out. The Exilarch then excommunicated Rabbi Saadia, who excommunicated the Exilarch right back. However, the Caliph sided with the Exilarch and forced Rabbi Saadiah out of Sura.

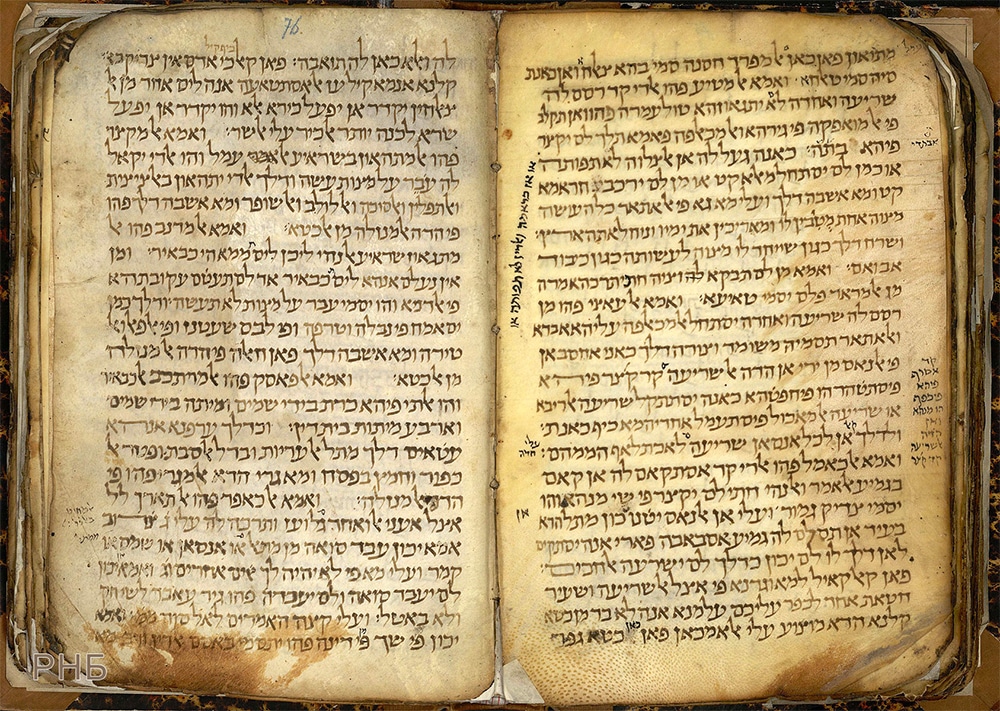

Stripped of power, Saadia Gaon decided to do what he always did: help the Jewish people. Throughout the Caliphate, many Jews embraced aspects of Islamic culture, especially Rationalism. Heavily influenced by Islamic and Greek philosophers, Rationalism argued for basing opinions on reason and observation, rather than the tradition of the Jewish Academies or the divine revelations of the Torah. As Rationalism spread, Jews struggled to synthesize these new Rationalist methods with their Jewish traditions. Many turned away from their religion entirely. Saadiah Gaon wrote that he “saw men drowning, as it were, in a sea of doubt, sinking in the waters of confusion.” Thankfully, the “drowning” men had Rabbi Saadia and, in particular, his masterpiece, The Book of Beliefs and Opinions.

Written during his exile from Sura, The book of Beliefs and Opinions blended Greek philosophy, Jewish theology and Arabic literary style into a single, unified understanding of the world. He argued that the divine truths of Judaism were the inescapable result of rational thinking. Because of this, religious leaders could embrace philosophy, while rationalists could accept religious doctrine.

Instead of letting Judaism break apart, Rabbi Saadiah united his people and paved the way for the Golden Age of Judaism and the concurrent rise of Rambam, the most influential Jewish scholar of the Middle Ages. Rambam argued that without Rabbi Saadiah’s guidance, “The Divine religion might well nigh have disappeared.”