I’m the youngest of three children. And I have this memory of something that happened all the time – that maybe you experienced too, if you have siblings. Whenever we had dessert, my brothers and I would argue over the size of the pieces. “You got the biggest piece!” “No, you got a bigger piece than me!”

Sound familiar?

After he was sick enough of hearing this, my Dad came up with a solution: “One of you cuts the cake, and the others get to choose their pieces first.” It’s kind of brilliant, right? Almost like power sharing or checks-and-balances.

All of us had a role to play—as either cutter or chooser—and the cutter was incentivized to make sure they were cutting fairly. And surprise, surprise: under this system, we quickly became happy with the piece we got. No more complaining!

Of course, this was a great life hack for my dad: Align the incentives right, and (hopefully) you’ll get the behavior you’re after. But on a deeper level, I think this solution exemplified a pretty beautiful form of balance, or Tiferet, which is our theme for this week.

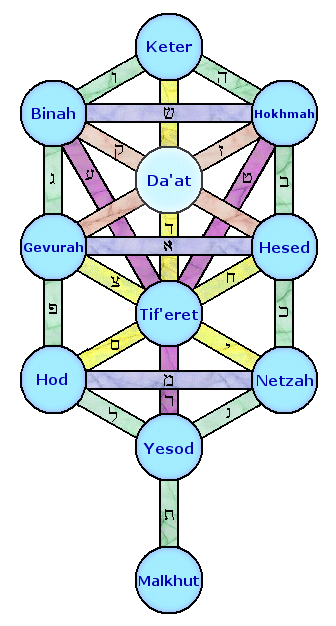

A quick refresher: we’re in the middle of the period of the Omer, this beautiful seven weeks between Passover and Shavuot that gives us an opportunity to hone in on a specific midah, or character traits. In Week 1, we talked about the trait of Hesed, or loving connection. In our second episode, we talked about Gevurah, the boundary- and limit-setting that comes with judgment and saying no.

Our theme for this week, Tiferet, is that balance point between the two, the equilibrium zone.

Let’s go back to the cake. What if my dad had played it out differently? What if he said, guys, stop whining, it’s enough already. That would have been a gevurah-oriented response: setting clear boundaries, but also maybe a bit harsh, kind of disciplinary. He could have gone even further and said, “If you complain, no cake!” Definitely harsh. Definitely boundary-setting.

He also could have gone in the other direction: “Okay, guys, you’re clearly struggling here. So I’ll cut the cake and make sure each of you gets as much as you want.” No limits, just a loving, cake-dispensing response. That would have aligned with the virtue of Hesed, letting the loving connection flow.

But neither of those options were right for the moment. The Hesed approach — unlimited cake — would certainly have conveyed his love for us. But a) it wasn’t really practical (we still would have argued), and b) it wasn’t going help us accept the inevitable limits that come with life. It would have spoiled us. So he didn’t go that route.

And while the Gevurah approach would have done a good job of stopping the complaining, emotionally it didn’t express love in the way he wanted to. The “thems that complain don’t get dessert” approach is a little too tough love.

So my Dad hit upon a third way, one that combined the loving connection of hesed with the boundary-setting of Gevurah. This is the way of Tiferet, that Goldilocks zone of balance — not too much, not too little, but just right.

Tiferet is that Goldilocks zone of balance — not too much, not too little, but just right.

Here’s a practice you might try this week, in the spirit of Tiferet. It’s inspired by an article on improv comedy by Tina Fey that I read years ago. She wrote that a great improv artist lives in a state of flow, open to whatever the moment seems to need and ready to step in when that moment is right.

It’s not about coming up with a great idea and then sticking it in there, and it’s not about just being completely reactive. It’s this kind of healthy zone in-between.

The practice, then, is to ask yourself this question when you’re confronted with a situation: What does this moment need from me? Before you respond, just take a breath and let that question linger in your mind.

Try asking yourself, “What aspect of Hesed, or loving connection does it need? What aspect of Gevurah, or wise boundary-setting? What can I uniquely contribute to the moment?”

Imagine, for instance, your boss comes to you with something urgent. “I need this item done asap!” But, you already have three other things that are top-priority and need to get done immediately. You might feel some frustration or fear or resentment start to arise. What are you supposed to do?

A Hesed approach might be simply say yes — you’ll figure out a way to get it done. You’ll work extra hours, you’ll call in reinforcements… you’ll figure out something.

That has some risks: to the plans you have with your friends that night, to your own health and wellbeing, and to your long-term relationship with your boss, who now thinks you’ll always say yes to an urgent request.

A Gevurah approach might be to say no—manage your boundaries and say, “There’s no way I can do that.” That has the value of sticking up for yourself (and keeping those plans). But of course it also risks your job. High stakes.

So take a beat, and take Tina Fey’s advice: What does the scene need from me? What would a Tiferet approach look like here?

It might look like this: You say to your boss, “I hear this is important and I want to get it done, of course. I also have these three other items that you’ve indicated are major priorities. Can we talk about how to balance these?”

This is Tiferet: combining the elements of Hesed, loving connection/saying yes, with Gevurah, boundary-setting and saying no. Just like my Dad’s solution with the cake, this Tiferet response can help us respond with wisdom to what might otherwise be annoying, triggering moments.

Tiferet combines the elements of Hesed, loving connection and saying yes, with Gevurah, boundary-setting and saying no.

This week, try this Tina Fey Tiferet practice. You can try it in a conversation at work or at home. You can try it when you’re walking down the street. You can try it in your car. Just ask yourself, “What does the moment need from me right now?”

Give yourself a few seconds or a minute. Try it out and see what emerges from just giving yourself that space. And let us know how it goes!

Blessings for the journey. I hope you’ll join us next time.