Schwab: Welcome to Jewish History Nerds, where we do exactly what it sounds like, nerd out on awesome stories in Jewish history.

Yael: I’m Yael Steiner, and my childhood dream was to stay in school forever.

Schwab: I’m Jonathan Schwab and I am in school forever.

Yael: Schwab, I’m really excited to have you teach me something for the first time in season two. What do we have on tap today?

Schwab: I’m so excited. Also, this is one of my favorite topics that we’ve ever done.

Yael: Wow.

Schwab: Because this is a person and a topic I did not know that much about and have really had the chance to dive very deeply into this one.

Yael: Learning new things is what this is all about.

Schwab: What I want to talk about today is how Jewish is political radicalism? And specifically, focusing on the character of a person named Emma Goldman.

Yael: I went to high school with someone named Emma Goldman. I believe her parents very intentionally named her Emma Goldman.

Schwab: That’s a move, yeah.

Yael: It’s definitely a move.

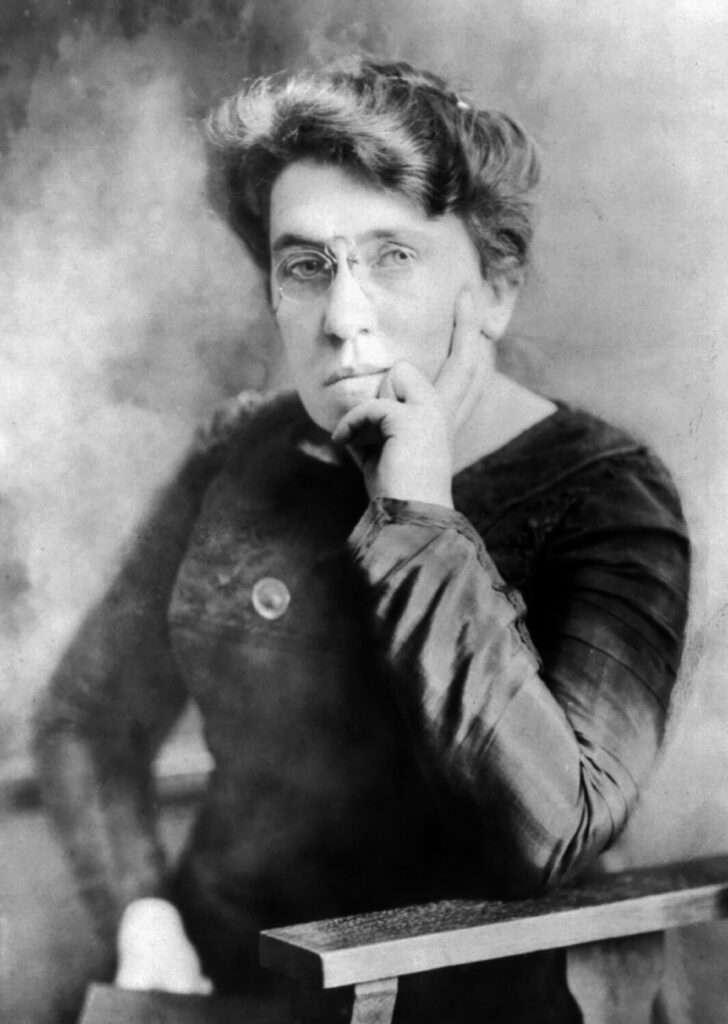

Schwab: So this Emma Goldman, not the Emma Goldman you went to high school with, but the Emma Goldman of many nicknames. Red Emma, the high priestess of anarchy.

Yael: Ooh. That’s like a Marvel cinematic universe name.

Schwab: Yes. And there’s a lot to unpack about that nickname also, which we’ll get to. She was born in 1869 in Kovno, Lithuania. Grew up a little bit in Russia, but she really came of age in the US. She immigrated to the US at the age of 18 in 1885, and she spent the best and most radical years of her career as a revolutionary in the US between 1885 and 1919 when she was deported.

Yael: Deported? Back to Lithuania?

Schwab: Back to Russia, and we’ll get there later. But didn’t work out great in Russia. She ended up sort of going around, couldn’t really find a specific home. She was allowed back into the US for one speaking tour in the 1930s, but she never really stayed in one place for very long after her deportation. And if you know one thing about Emma Goldman, it’s that she was radical. The title of a book that I read about her is Emma Goldman: Revolution as a Way of Life, and her life is solely focused on revolution, on radical change, on inspiring and motivating people to see things the way that she saw them.

Yael: She sounds awesome.

Schwab: Yes. Let’s talk about how radical she was. When we say radical, what do we mean by radical? She was anti-religion, she was anti-capitalist, she was anti-state. As an anarchist, she pretty firmly believed there shouldn’t even be a government or a state. She was anti-war. She openly advocated for birth control long before that was acceptable. She was very anti-Zionist, really spoke out against it, mostly because, she didn’t think anyone should have a country. There should be no countries.

Yael: Was she pro anything? Birth control.

Schwab: She was pro birth control. She was pro cooperation, mutual existence, mutual aid, individual liberty obviously, the most important, that people have the right to exercise their freedoms and be themselves and be authentic.

Yael: She sounds like she would have fit in well at Woodstock.

Schwab: Yes, there is in the ’60s and ’70s, sort of a revival of interest in a lot of the movements that she was part of and sort of refiguration of anarchy a little bit, but not to the same extent, it’s sort of as a fascination as opposed to an actual legitimate movement.

Yael: So I think, when I’ve heard of her and also you mentioned that she’s sometimes known as Red Emma, I think I always associated her expressly with socialism or communism and it doesn’t sound like what you’re saying that she really had an ism that spoke to her.

Schwab: Anarchism, which is sort of just like there is no thing. Yeah, I think she thought that socialism was a better path than capitalism to achieving her ends. Red Emma is a misnomer because she really isn’t a socialist. She wants to do away with pretty much everything. Speaking of things that, is she pro anything? This is all happening at a time before women have the right to vote in America. Now, you might think that she was a suffragist and thought that women should have the right to vote, but she didn’t oppose it, but she definitely was against the suffragists.

Yael: Was that because they, by agitating for the right to vote, they were therefore supporting the concept of powerful government or giving the government power?

Schwab: Yes, exactly. Exactly.

Yael: So she was willing to not have women participate in the government that actually existed, just so that she could make the point.

Schwab: Yes. So she didn’t oppose women’s suffrage, but she did hate suffragists. She felt that they were focused solely on one issue. They were out of touch with the common person, and exactly as you said, she was against voting. She described it not as a right, but an imposition and another method of state control, and she had this quote, which I want to read because also I want to just appreciate her language. She was just a great writer. “Women clamor for that golden opportunity,” she wrote, “that has wrought so much misery in the world and robbed man of his integrity and self-reliance.”

Yael: Wow.

Schwab : Why would you want to vote? Because voting is horrible, and is another way for you to lose your sense of individual freedom and liberty and self-reliance.

Yael: So interesting. My argument would be that as much as voting yields wars, not voting also yields wars.

Schwab: Your point that you made before of, you should vote for the government that currently exists. I think that’s not the world that she lived in, she thought about things in terms of their ideal shape and wasn’t really a pragmatic evolution, not revolution, we need to change things slowly. She thought about things as they should be. One person described her, I forget where I read this, but said her biggest problem is that she was 8,000 years too early.

Yael: Wow. So we’re still like 7,900 years ahead of where she would be.

Schwab: Right, of where her ideas really be popular. Before we get to the question of violence, she always carried a book with her at all times.

Yae: Smart lady.

Schwab: Smart, yeah, because she knew that she would likely and very often was arrested. So this way she would have something to read while she spent time in jail.

Yael: That’s very smart. She left Lithuania. She came to the US. I’m assuming there was a time period during which she was not a famous rabble-rousing anarchist. How did she get from new immigrant to the United States to whatever it was that she was doing, even on a small scale?

Schwab: Yes. So let’s talk about her life story, and I guess we’ll come back to the question of violence and where she stood on that issue. She grew up, complicated family history. Her parents, it’s a very unhappy marriage. It’s a very unhappy home. She’s living in Russia. She very much hates it there. Her parents, by the way, they’re Jewish, but they’re secular, she did not grow up religious. She wants to be in America, says that’s where she wants to go.

She was a pretty good student, but failed to get into the equivalent of high school because her religious teacher refused to give her a character reference saying she was, in short, a terribly awful child who could not listen to anybody or be obedient to anything. Her father also was a very strict disciplinarian, and it didn’t work on her. No matter how hard he beat her, she decided at a young age that she was never going to give him the satisfaction of crying in front of him. So no matter what she was subjected to, it only seemed to make her will stronger.

She decided that the place that she belonged was America, told her father that, he refused to send her there, said she would be better off being married off. The only thing that young Jewish girls need to know how to do is make gefilte fish and noodles and babies, but that’s not really how Emma saw herself. So she basically said, “If you don’t let me go to America, I will drown myself.”

Yael: Oh my God.

Schwab: … in the local lake.” And it seemed like that was pretty serious threats so finally her father relented and sent her to Rochester, New York where her older sister had already immigrated. There turns out America was not as great as she had imagined it to be. She worked in a sweatshop in terrible, terrible conditions, was surrounded by other people who were in just terrible conditions, after doing 80 hours of work a week, being paid a small amount of money, and then having deducted from that money, the cost of the materials and the cost of the chair and being fined for bathroom breaks and all the terrible labor practices that were going on in turn of the century America. She also is married off, it’s very unsuccessful. It’s a very unhappy marriage. She divorces him. basically nothing is going right. She makes her way to New York City where she deliberately comes there because she had been reading a lot of radical anarchist literature and especially a newspaper published by a man named Johann Most.

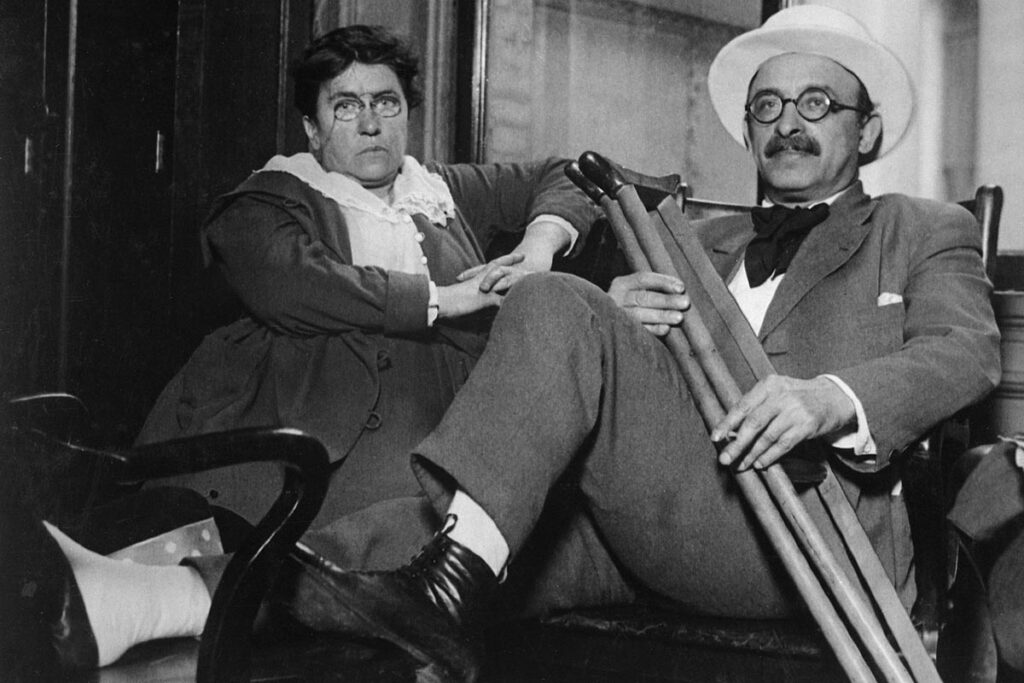

So she comes to New York City to sort of meet up with this group of anarchists, and one of the first people she meets while she’s there is a guy named Alexander, also goes by Sasha Berkman. She meets him basically right on arrival to New York City, and they have a lifelong relationship, sometimes romantic, sometimes just friendly, sometimes like politically collaborative. Then she falls in very quickly with this anarchist crowd but it becomes obvious to everybody, including Johann Most that she is really talented at speaking. So he starts to send her out as his representative, as his protege to speak and spread his ideas on his behalf.

Yael: Were there other women who were prominent in this arena, or was she sort of a trailblazer in the anarchist community as well?

Schwab: There were women included. While they were progressive in the public sphere, in many of their interactions personally, were not that progressive, and she was subject to a lot of sexism, and especially as a young woman she was often… nowadays, we would call it sexually harassed by a lot of the people, including this guy Johann Most, who took her under his wing as a protege, but was very interested in her and she sort of just kept rejecting him. She’s like, “I’m not interested in that. I’m interested in your ideas, not what you seem interested in.”

Yael: Right, I’m getting The older professor – young student at office hours vibe.

Schwab: Yeah, a hundred percent.

Yael: Okay, got it.

Schwab: While she’s going out on speaking tours and sort of supposed to be spreading Most’s ideas for him, she realizes at one point in speaking that she wants to talk from her own heart and say her own ideas and realizes that she’s got a lot to say, and she doesn’t just have to be the vehicle and the voice for other people’s ideas, but she has a lot of her own thoughts to articulate, and apparently those speeches start going really well.

And also, keep in mind, this is a really popular thing to do at the time. This come to a town and lecture and people would show up to it. That was a major source of entertainment in the early 1900s, so there really were hundreds and sometimes even thousands of people who would come to hear her speak.

Yael: Was she traveling all over the country or was this mostly in New York?

Schwab: At the beginning it started out in New York, and then she started traveling all over the country, and she writes in her autobiography about how that really helped not just perfect the delivery of her ideas, but really sharpened her thought on these ideas that she would travel all over the country, meet many different types of people, see what ideas resonated, what didn’t resonate, what people would say in response. Early on, she had this experience where she was talking about something and one of her very powerful speeches about the way the world should work, and a worker said to her, calls out during her speech, “That’s really nice for you, but what we really need right now is a one-hour break during the day. That’s what we need to be advocating for.” Sure, I’d love to live in the world that you’re talking about, but I need to be able to eat lunch during the working day.

Yael: Incrementalism was not her thing.

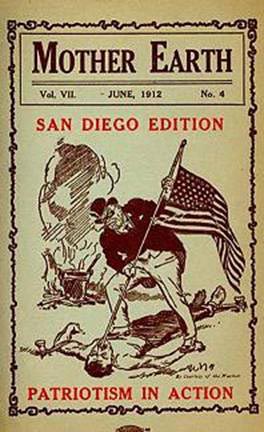

Schwab: Right, but she does start to understand what it is then, that is a helpful message for people to hear what it is that when she’s doing a call to action, what actions are actually helpful and constructive and supportive. So she really does, through traveling and through speaking all of the time, really hone her craft and really start to hone her ideas as well, and comes to be really, really good at these inspirational fiery speeches that get people excited and ready to join her movement and it branches out also into, she starts a newspaper called Mother Earth that has some pretty wide circulation too, that there’s a lot of writing in… all of this early on isn’t even taking place in English.

Yael: Oh, wow.

Schwab: Yeah, she learns English, she is sent to jail for a one-year sentence for inciting violence, and she makes good use of that time. And during her one year in jail, which she also talks about as really instructive in thinking about how so much of our society functions on oppression and no place is that more obvious than jail, but she puts that time to good use studying English and comes out of jail after a year really being able to speak in English as well as she could in Yiddish, which is what she’d been giving a lot of her speeches in before that point.

Yael: So was most of her audience Jewish?

Schwab: A lot of her audience was Jewish. Even later, once she could speak in English, she would often travel to a town and speak twice, once in English, once in Yiddish. And her Yiddish lectures were very well attended, even when the English ones weren’t and yeah, and that’s sort of the question around this entire thing of, she did not talk about her Jewish identity a lot. She wouldn’t describe herself as, I’m a Jewish anarchist or I’m a Jewish radical, but being Jewish was so tied to everything she was and everything she did, and so many of the people around her were Jewish. I guess the real question is, are her ideas then Jewish? Is there something Jewish about this, and what does that mean when we ask that question even?

Yael: Well, I wonder if part of it is that at that time in particular, so many of the new immigrants, particularly to New York, were Jewish. Obviously, there were others, and I know that especially at that time before the Chinese Exclusion Act, there were tons of Asian immigrants as well. But I think that because there were so many Jewish immigrants and they were so destitute and being taken advantage of in the sweatshops and in the factories and whatever industries they were working in, that their religion or the overarching ethos of their life became workers’ rights because that was the only thing that impacted their life at that time.

Schwab: Exactly what you’re saying, if you’re talking about immigration and labor in early 20th century America, you’re talking about Jews because that’s who that population is. But there’s a question beyond that I think of is it just a historical coincidence or is there something more deeply Jewish about it? Or the flip version of that question, even if, I don’t know, generations of studying the Talmud impacted the movement for workers’ rights, whether it did or didn’t, the other question is, well, once this has been the case, once Jewish American identity has been tied to this question of workers’ rights, then there is something Jewish about it in terms of identity moving forward, it’s like bagels.

Yael: Oh, certainly. We know that throughout the 20th century, socialism in the United States was certainly populated by a lot of Jews and a lot of them, I think second and third generation whose parents had come to the Lower East Side in the 1880s, early 1900s. Jewish summer camps, a lot of them were socialists, there was sort of this cultural tide that swept over particularly the less observant Jewish population, it gave them a community center to be part of these various labor movements.

Schwab: Yeah, and there’s something Jewish, I think, about this desire for community like Jews in America, either because Jews are… whatever word you want to use, inclined to communal structure in some way. I think all people are, but maybe there’s something Jewish about that, and also were often excluded from a lot of other opportunities. So this was the way for them to continue to form or affiliate with the community in a lot of ways. Rewinding for a second, another important historical occurrence that did have a lot of effect on Emma and a lot of people like her from Russia is in the 1830s, a couple of decades before she was born, Tsar Nicholas the First wants to assimilate Jews as much as possible into Russian society and he has the brilliant idea of what if one way to do that is make sure that we can conscript Jews into the army.

There previously been an exemption, you could pay a fine to get out of the army, which is basically what most Jews did, and he gets rid of this exemption and in addition to making sure they’re not exempt, we’re going to have this conscription start with enrollment in a military school at the age of 12, because if we’re conscripting people at the first time when they’re 18, they already have developed their identity in some way so it’s not helpful at that point to get them into the army.

Yael: They need to be indoctrinated at a young age.

Schwab: Yeah. So he says, we got to get people at the age of 12, send them to six years of military school, and then have them serve, do their years of army service. Which years of army service… you know how many years that is?

Yael: I don’t.

Schwab: It’s 25.

Yael: Wow.

Schwab: Yeah, I was like, maybe it’s a couple, maybe it’s five would seems like a lot.

Yael: It’s interesting because just last night I was talking, my dad and I were talking about my grandfather. My grandfather had enlisted in the United States Army Street out of high school. And he was supposed to be done with his three years in the army in February, 1942. And then in December, 1941, the Japanese bomb Pearl Harbor and he ended up in the army for four more years. So he was supposed to be in for three, but then he ended up in for seven, which to us sounds like a very long time, but compared to 25…

Schwab: That’s not even a third of 19th century Russian military service. Yes, so Tsar Nicholas says, we’re going to do this, and the six years in military school from 12 to 18 don’t count towards the 25 also.

Yael: Got it.

Schwab: It’s 25 starting at the age of 18. So this is your life.

Yael: And this influences her significantly.

Schwab: And what influences her is, rather than the Russian government deciding who is going to be conscripted into the army, they pass that on to the local Jewish communities and say, “You’re going to decide who it is, who’s going to be sent at the age of 12 to six years of military school and then 25 years of army service. We need 10 Jews from your community, Jewish community leaders, rabbis, et cetera. Tell us who your 10 Jews are,” which there’s something very kind of like Hunger Games-y about that.

And basically exactly what you would think happened, happened, which is the rabbi’s son never went, the wealthy person in the community, their son never went. And it created a very corrupt and demoralizing and upsetting community structure in Russia. And that’s the context in which Emma grows up. And I think that plays a huge part in her total distrust of authority. Distrust doesn’t even do it- Her total… trust that authority is corrupt, is out to get people, does not serve anyone’s purpose but its own.

Yael: I got it.

Schwab: And she is part of a whole generation that rebels very much against authority. And sees religious ritual community as yet another instrument of control and coercion.

Yael: So when does she turn from impressive self-taught English speaker/orator to agitator for violence and deportee?

Schwab: Yes. And I think this is an important description to include, J. Edgar Hoover, goes on to be the head of the FBI, described her as the most dangerous woman in America.

Yael: Nice.

Schwab: How does she turn into that? And I think we need to get to this question of violence and what role violence plays in this movement for anarchy. She waffles on it a little bit. She never advocated for violence, but she defended a lot of people who did advocate for violence. There was an early occurrence, this is when she’s very young, the Haymarket riot. Many people are killed. It started out as a strike, but becomes a real actual battle wage between police and strikers and that for her is sort of a spark. She calls it an epiphany. Epiphany is an interesting word to use and there’s a lot to talk about there of the use of religious language, we mentioned at the beginning, the high priestess of anarchy and what role religion plays in all of this.

Yael: She has a calling.

Schwab: She does. There’s something that seems very religious about all of it. She’s preaching. She talks about living your life for the cause, which sounds an awful lot like living your life for a religion. There’s something very messianic also about the whole thing.

Yael: Well, she is trying to redeem the downtrodden masses.

Schwab: Exactly, yes. She wants to bring about redemption in the world.

Yael: But one thing you said earlier that struck me was does hundreds of years or thousands of years of Talmudic learning yield any of this? I really might be using this term incorrectly, but the dialectic, the opposing forces of two ideas, so of two people learning a bit of Talmud and arguing about it and presenting their ideas vocally to one another in the study hall. And I think as a people, Jews have honed that skill. Even not in public, but within their own families and I think she’s bringing that into the crowds. I don’t think she probably ever spent any time in a synagogue or a study hall based on the way she grew up, but I think you know, she definitely was influenced by the type of learning and communication that Jews had with one another, specifically in Lithuania, around the time that she grew up.

Schwab: She was definitely deeply aware of Jewish and by that I mean religious life, that was one of the things that she did she would… dancing was very important to the anarchist movement, as I’m sure you know, this is a big part of it.

Yael: As it is to all movements.

Schwab: As it is to all movements. But she would host this masquerade ball once a year on Yom Kippur. And it could be any day of the year, but there’s something very deliberate about that.

Yael: Oh, for sure.

Schwab: There’s something so Jewish about the masquerade ball has to be on Yom Kippur.

Yael: If you’re not a part of it, you’re specifically going to have to push someone’s buttons about it.

Schwab: Yeah. And, there’s something so Jewish about the carrying a book with you so you can read it in jail.

Yael: It’s a great call.

Schwab: Yeah, I feel like there are a lot of people who in very different contexts would carry a religious book, a Sefer or a part of the Torah or a Talmud or something. So for her, it wasn’t the Talmud, that’s not what she was carrying but there’s something very Jewish about that thing of just always carry a book because you never know when you’re going to wind up in jail and you want to have reading material.

Yael: Yes, I think this is definitely ripe for a movie. I think maybe the climactic moment of the movie would be one of these incitements to violence.

Schwab: Going back to the violence thing, the most famous incitement to violence, which again, she would say, “I don’t think the violence is the answer.” Sasha Berkman, who I mentioned before, whom she was very close with, served 15 years in prison for attempting to assassinate the owner of a factory, I think it was, and attempting to assassinate, not he had a plan. He shot this guy three times and stabbed him.

Yael: So what you’re saying is only an attempted assassination because he was bad at it?

Schwab: Yes, exactly. It was an attempted assassination only because he was very bad at it apparently. Had the person died, he would’ve been sentenced to death, which is so fascinating if you think about it. If he had been better at it, he would’ve been sentenced to death and executed. He didn’t kill the guy, even though he had every intention to, so he was only sentenced to 22 years in prison. And Emma-

Yael: That’s less than the Russian army.

Schwab: Yes, right? She spent years of her life trying to get him out of prison, he only served 14 years before later being sentenced once again and then deported along with her. But it’s hard to say this is a person who was not pro violence if she spent so much of her time defending and trying to free someone who was in jail for violence. But the most famous example is there was a President of the United States named William McKinley.

Yael: Heard of him.

Schwab: I’m 90% sure his first name is William.

Yael: You’re good.

Schwab: And he was assassinated by a person who said he was inspired by Emma Goldman and had met with Emma Goldman and considered himself a follower of Emma Goldman. And now she never told this guy, Leon, I would totally butcher the pronunciation of his last name, so I’m not even going to try. She never told him to assassinate the president, but he interpreted it that way. He saw himself as acting out everything that she spoke about in assassinating the President of the United States at a time when a lot of anarchists were talking about assassination, talking about that, not just for political leaders, but for capitalists, for a lot of their enemies. You can’t separate her from violence and pretend like she is some total pacifist who never had anything to do with violence in her life. She was put on trial for this. The charges were dropped. It really could not be proven that she is the one who incited directly this assassination, but it is pretty closely tied to her.

Yael: There’s a Stephen Sondheim musical called Assassins that tells the story of famous assassins throughout history, and she is prominently featured in the musical. So she is definitely conflated with an assassin in history, at least by Stephen Sondheim, American treasure.

Schwab: Which also talking about her and violence is so fascinating because the thing that she eventually gets jailed and deported for was anti-war activism. She is firmly against World War I, she saw it as a way for capitalists to further oppress people, to kill off more workers, and she advocates against the war. She’s against conscription, which makes a lot of sense if you think about her background. And she’s so firmly against the war at a time when being patriotic and nationalist was becoming so important that she eventually was put on trial for this and deported from the country for advocating against war.

Yael: So when she goes back to Russia, is she associating with the very famous revolutionaries and big characters there?

Schwab: Yes, so she was grief-stricken to leave America, it seemed like she did have a very deep, strong love for America for the freedom of speech that it so often offered, and that she very much wanted to continue the expansion of. So she was not happy to be deported and sent back to Russia but she was excited at the opportunity to be sort of in the center of an emerging revolution that she saw as representative of her ideas. And she was very disappointed to find that Soviet Russia and the Bolshevik movement did not live up to the ideals that she really thought of. She met with, I think it was Trotsky, she had one meeting, she and Berkman together, and they felt like they were totally dismissed.

And this was just another iteration of concentrating the power in the hands of the few and not really living up to the ideals that they were supposed to. And after only a couple of years in the disappointing Soviet Russia, she moved on to Sweden for a little bit. She was not welcomed in most European countries. Eventually, she settles in London, she’s in France for a while. She goes to Canada at some point in the late ’30s, I think it was ’38 or ’39. She is finally, after a lot of begging and pleading, allowed to come back into America temporarily to give a lecture tour but with very strict controls about what it is that she can say and do, which she acquiesces to, which is very fascinating because that’s-

Yael: Interesting.

Schwab: … a real turn of here she is.

Yael: She had been worn down by life at that point.

Schwab: Yeah. The newspapers loved her whole life. The media had an incredible fascination with her. They would decry and denigrate her, and they would talk about Red Emma, and they would talk about how scary and dangerous she was. And then they would print in its entirety every word that she spoke, which they know some people are going to read and be inspired by. And they’re sort of this very complicated love hate relationship with her.

Yael: Kind of sounds like cable news.

Schwab: Yeah. Nellie Bly is a famous reporter of the early 1900s, does this in-depth interview. I think it was a profile on Emma while Emma was in jail.

Yael: Oh, wow.

Schwab: And Nellie Bly is very sympathetic. It is very odd because reading it, in every single article about her, they go on and on and on about her physical appearance and her physical attributes, which is so off-putting a 100 years later, because, so obviously-

Yael: You’re right, we never talk about women’s looks now.

Schwab: We still do but it’s obvious that this is way too much and too inappropriate, whereas…It’s not the New Yorker style. I’m profiling someone, so I’m going to give… the opening to my paragraph is the color of her hair.

Yael: “She comes in in black turtleneck and slacks.”

Schwab: Yes, exactly. It’s going on and on about the shape of her face.

Yael: Oh, wow. But I think, this might be a false memory, that she was known to be an elegant person.

Schwab: Yes. She dressed up nicely and I think as with many things about her, it was deliberate in her choices and her appearance was part of it. Which is fascinating because she talks about being authentic and being true to herself. But at the same time, I think she was very aware of how her message would be received and therefore what form her message should take, so she played to her audience.

Yael: And that, I guess, was authentic to her or she felt it was authentic to her.

Schwab: Yeah, and I think that she really did feel like she lived her life in line with her ideals.

Yael: I want to read so much more about her.

Schwab: She is a very interesting person to read about. There’s this very sanitized version of her that’s popular now, and people think about her and or will ascribe quotes or ideas to her.

Yael: She is the, “If I can’t dance, I don’t want to be in your revolution” person?

Schwab: Oh my gosh, that quote is so important. Yes. People quote that, but do you know the background of that?

Yael: I don’t.

Schwab One of the anarchist balls, as there were, and she was dancing, I think, pretty provocatively and pretty energetically. And one of the people said to her, “You won’t be taken seriously for your ideas if this is the way you’re dancing and the way you’re behaving,” and she responded with something like, “If I can’t dance, then I don’t want to be part of your revolution.”

Yael: It’s amazing.

Schwab: Yeah. I don’t know what people mean when they quote it, but I don’t think they fully understand the exact context of the revolution part of it, certainly. But yeah, so there’s sort of a reclaiming of her as I think this neat figure, there was a project at some point to publish some of her papers, and there was money even for it from a government agency of some type, I forget what it was, the National Endowment for the Humanities or something like that. And one of the articles said, this is so fascinating because here’s this person who was literally deported from this country and seen as seditious and treasonous, and now the federal government is part of supporting this new view on her as-

Yael: It would be if they supported a project about John Wilkes Booth.

Schwab: Or the person who inspired John Wilkes Booth. Yes, there’s so much more to unpack and to learn about. We’ll put links to lots of stuff in the show notes. I strongly recommend Revolution as a Way of Life, which is a pretty short, pretty digestible biography of her. We’ll put a link to that as well as a number of other stuff.

Yael: Before you said that, when you just said, “I strongly suggest Revolution as a Way of Life,” I was like, oh, wow. She really did influence you.

Schwab: I have been very inspired by Emma Goldman. I do think we all need to live life authentically, free from the shackles of any sort of oppressive control. I will no longer be voting. It is yet another way for man to be robbed of his integrity and self-reliance.

Yael: That’s amazing.

Schwab: Yeah, and I’m looking forward to the rest of this season, and I hope that the rest of our topics are as interesting as this one, because this really sent me down some rabbit holes.

Yael: Well, our first two topics have been literally killer. So we’ll see.

Schwab: Hopefully, a little less violence.

Yael: A lot less violence, but a lot more dancing.