Schwab: Welcome to Jewish History Unpacked where we’ll do exactly what it sounds like. Unpack stories in Jewish history that are…awesome.

Yael: I’m Yael Steiner. And my childhood dream was to stay in school forever.

Schwab: I’m Jonathan Schwab and I am in school forever.

Yael: And we are two non-professional history fans who are not embarrassed to be massive nerds. In particular, history nerds.

Schwab: Yeah, and in even more particular, Jewish history nerds. And on this show, we’re super pumped to unravel some pretty major events in Jewish history. Spoiler alert, there’s a lot to learn, and some of it is pretty bonkers.

Yael: And here’s what that means, practically, for this podcast. Each week, Schwab and I will take turns researching the heck out of a crazy story from the last 4,000 plus years of Jewish history – and then we will, kinda, teach them to each other.

Schwab: This week, Yael, it’s my chance to be telling you a story and I have a doozy for you.

Yael: I am so excited.

Schwab: How much do you remember about the history of the French Revolution?

Yael: I have seen Les Mis several times.

Schwab: Okay, that’ll help.

Yael: Yeah. Similar to the American Revolution, I think. There were the common people trying to overthrow a classist, hierarchical system in 20 words or less, maybe.

Schwab: Yeah. I mean, that’s pretty much it. A lot more details involved, but that’s the gist of it and the character at the center of today’s story, who’s very involved in this question of how much should Jews be integrated into the society around them and how many of their priorities do they share, is a person who became pretty famous during the time of the French Revolution. You might have heard of him.

Yael: Lafayette?

Schwab: Ooh, that’s a very good guess. It’s not America’s favorite fighting Frenchmen. But a different famous Frenchman, who is also known for fighting.

Yael: Napoleon.

Schwab: Yep. Napoleon Bonaparte, the little known French ruler, the little known and not actually-

Yael: little-

Schwab: … that little.

Yael: … little.

Schwab: Yeah. Famously incorrect, he wasn’t actually as small as people think he was, but Napoleon was a key figure in asking Jews a series of questions that are really still pretty interesting and relevant to us today.

Yael: How did Napoleon interact or interface with the Jews?

Schwab: Yeah, how did we get to this? Yeah. Let’s rewind for a second and talk about… Where do you want to start, the French Revolution or what the status was of Jews in France?

Yael: Start with the status of the Jews in France and then you’ll queue me in. I have a hunch it might have changed at the time of the French Revolution?

Schwab: Yeah. Along with many things in France, yeah. Jews in the medieval period in Europe were basically thrown out of every country that they were in, generally. Thrown out of England, thrown out of Spain, thrown out of Portugal. They were thrown out of France, too. That was the status for a while. You couldn’t really be Jewish in France and there were a couple of different smaller communities that existed kind of on the fringes of French society.

There was, on the one hand, these Portuguese Jews, most of whom had converted at least nominally to Christianity, but were still kind of living as Jews. They had a community of these Sephardic, Portuguese Jews in the south of France and basically they were kind of just like the way one person described them, Jews with Christian driver’s licenses. They were allowed to exist because on paper they looked like Christians, but they were still Jews. Then later as France expanded and took over some German territories, they absorbed some of the Ashkenazi Jews in the East and there, they had some Jews, who were more integrated into society, professionals, doctors, those types of things. But they also had some very isolated, very, very traditionalist, very religious Jews, who all of a sudden were part of France and France didn’t know exactly what to do with them.

Yael: But they weren’t allowed to be citizens in France, correct?

Schwab: Oh, no. They were not citizens in France, along with many other types of people, including women, and then the French Revolution sort of upended this entire question and said, “Who does get to be a citizen?” With that background, then let’s get to the French Revolution part. Does that make sense?

Yael: Yes.

Schwab: The very brief version of French Revolution because it’s been a while since 10th grade, 11th grade?

Yael: Yeah. 1789, also.

Schwab: Yeah. In 18th century France power was shared between the three estates equally. There were three estates and every estate got one vote. One estate was all the clergy, one estate was the nobility, and one estate was everyone else. And not even everyone else because not really the Jews! Everyone else, just like, the white Christian men was the everyone else-

Yael: Like the Jews didn’t really rise to a level of personhood that would have placed them within an estate?

Schwab: Correct.

Yael: Like the estate separated “people,” but there were a whole other group of humans, also people, who were not included in that.

Schwab: Exactly.

Yael: Okay.

Schwab: This estate system, the Estates General, was already an incredibly unfair system and you’re right, Jews weren’t even in it.

Yael: Got it.

Schwab: But as it turns out, people did not love the fact that about 5% of the population had the majority vote because two of the estates could just vote against the other estate and also, the nobility and clergy didn’t have to pay taxes and had most of the money.

Yael: It’s always taxes. It’s always taxes.

Schwab: It’s always going to come back to taxes. Taxes, taxes, and interest. Interest is a big deal. But the third estate, which again, is most of the people in France, kind of don’t like this anymore. They overthrow the king, they overthrow this system, they go through a period of a lot of radical changes. And you’re right, it’s very similar to the American Revolution, and happening at the same time with a lot of the same characters, too. Lafayette, who was French and was very involved in the French Revolution, was also involved in the American Revolution. Thomas Jefferson’s in France for a lot of this until he comes back to America in act two, famously.

Yael: Yes, yes. This is going to be a musical heavy podcast, I’m beginning to understand.

Schwab: The French write their version of the Declaration of Independence, which for them is the Declaration of Rights of Man and Citizen, and man in that case does mean man, not woman. There was-

Yael: Got it.

Schwab: … a brief failed movement to get women more involved and the French agree in this document that all citizens are naturally free, they have rights, and they work together to create a political system to protect those rights. There’s this huge feeling of all of France needs to come together. They have this motto, which is still the motto of France to this day, liberte, egalite, fraternite, freedom, equality and fraternity, and they really feel like all of France has to join together and work together to create a new system of government.

Yael: But I’m assuming that like the American Revolution, when they wrote the Declaration of Independence and went back and forth in the Constitution, Bill of Rights, the Americans debated when they said, “All men are created equal.” We just talked about how the estates didn’t really include a lot of these marginalized individuals. So, were the French also thinking about that in their Declaration of Independence situation?

Schwab: Yeah. That’s exactly the question. As they’re coming up with this idea, all citizens have natural rights, all of them deserve to be citizens of France. The question that kept coming up is, are Jews citizens and really sub-question, are Jews people? Are they people? Do they deserve to be treated like people?

Yael: A question that is still being asked today.

Schwab: Yeah. It’s, unfortunately, not a fully resolved issue for some people. But after they draft this document in 1789, as some Jews start saying, “Hey, we are people and we would like to be treated as citizens,” the French government, or a series of different governments do start giving citizenship to these Jews. In 1790, first to the Sephardic community, the original Portuguese, who were more integrated culturally in terms of language and dress and work. But eventually also the Ashkenazim, even in Eastern France, who dressed differently and often spoke Yiddish instead of French, were much more religiously conservative and insular, they too get citizenship in 1791. And they really start becoming part of France. The term, not coincidentally, that historians use for this, is emancipation. This is the emancipation of the Jews and the welcoming of them into society and into citizenship.

Yael: How did that go? Obviously, it’s a political distinction, but were their friends and neighbors accepting of this? Was there violence?

Schwab: It went smoothly and there were no issues whatsoever that ever came up.

Yael: We all lived happily ever after.

Schwab: And that’s the end of our episode. No, great question. It did not always go smoothly. There were issues with this integration and with this emancipation, and there were people who did not love it. There was a series of antisemitic incidents and a major thing that came up a lot is as these Jews became citizens and had access to new forms of employment, sometimes the things that they did in the jobs that they took on angered some of the French people who had formerly been doing those jobs a little bit differently.

Yael: … it was a ‘Jews will not replace us’ situation.

Schwab: Yeah, definitely. Whatever the French equivalent of Jews will not replace us. We’re not talking about a huge number of Jews. France at this time has about 30 million total people and there are maybe 30,000 Jews.

Yael: Oh, wow. Okay.

Schwab: So we’re talking about really a quite small number of Jews, but this very small number of Jews do begin to have a real effect in some areas of the economy. As they’re able to start some of their own businesses, they start to be really, really successful in some areas of business and the French, especially the merchant guild people, who had been doing things a certain way for a really long time, were now really challenged by these Jews who had this natural network, new people in other places could connect with them, were able to find lower prices for things, were producing things in larger bulk, and selling them, and doing all sorts of things that were kind of driving some of these non-Jews out of business.

Yael: How does Napoleon figure into that?

Schwab: So they complained to the government, which at that time was Napoleon.

Yael: Got it.

Schwab: Napoleon at this point had risen to be the emperor of France and France had gotten a lot bigger by this time, too.

Yael: Emperor does not sound very post-revolutionary.

Schwab: Oh, it was wild. The French Revolution swung back and forth between a system where no one’s in charge and everything is a vote of the people and one guy is in charge and we’re just going to let him go on military campaigns and eat half of Europe for breakfast. We were in one of those stages at this point and France really also encompassed, like their territories encompassed, a large portion of Italy. This was a pretty big France and they complained to Napoleon. Napoleon asked this question of like, “What’s the story? Do these Jews want to be part of France or do they have their own ideas in mind really? And who’s in charge of them anyway?” He, Napoleon, did not really do things halfway. I don’t know if you knew that about Napoleon.

Yael: I feel like a lot of what I know about Napoleon is probably inaccurate, but the grandiosity thing is pretty well-known.

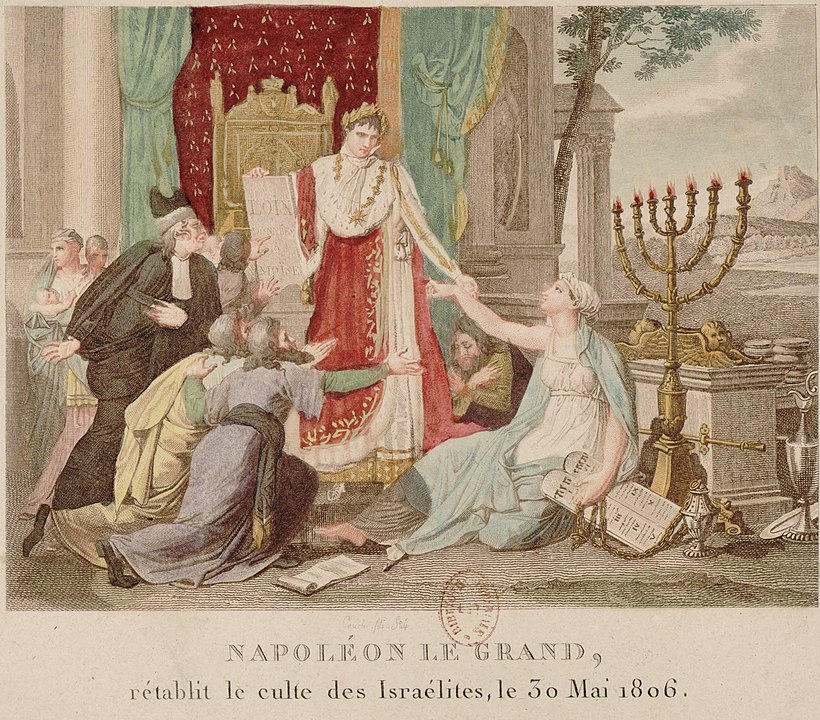

Schwab: Yeah. He was not a small measures person. Napoleon, rather than saying, let’s research this and just ask a couple of people, he convenes a body, the Assembly of Jewish notables, that’s what it’s called, the Assembly of Jewish Notables.

Yael: It’s a good name.

Schwab: It’s a great name. He has a series of questions for them where he will once and for all determine what the story is with Jews and what it is that they want.

Yael: Is this like an investigation, like he is trying to figure out what to do with the Jews?

Schwab: Yeah. He sends them these 12 questions, and this assembly has to give him answers. They represent these Jews and then not only does he get answers for them, but once they give him answers, he says, “All right, now the answers that you gave me, these have to be binding on Jews,” like these are the answers, this is what Jews do. What he then next has them do is he hears of a body called the Sanhedrin, which is the ancient Jewish court that existed in the time of the Talmud that had not met for 2000 years, and he says, “You’re going to convene a Sanhedrin and you’re going to pass this into law and it will have the status of law and the same status as the Bible and the Talmud in all Jewish communities.”

Yael: Okay. That first all sounds wild and I have a lot of questions, but let’s just take a step back, how did he decide who he was going to ask these questions to?

Schwab: Oh, he said the Jews should decide. He’s like, I don’t know who’s important of the Jews, so when he said there’s an assembly of Jewish notables, he kind of said you assemble your notable Jews.

Yael: Got it. He was a delegator.

Schwab: Yes. In this area, yes. This was a wide swath of people. This was not one community of Jews just sent a whole bunch of people. Every community was represented, and there are a lot of jokes about Jews along this line, but this was not a body of people that I think could easily come to any simple decisions because this was a whole bunch of Jews from different backgrounds and different orientations who needed to come up with answers.

Yael: So what were these questions?

Schwab: Let’s get to the questions. Roughly splitting them up, I’m paraphrasing them, these are not the original Napoleonic French questions that I’m going to read now.

Yael: You’re not under oath.

Schwab: But splitting them up roughly by topic, he has three questions about marriage. One, do Jews practice polygamy? Two, do Jews accept divorce? Because divorce was still at that time a really big deal. And three, can Jews marry non-Jews?

Yael: Did he want Jews to be able to marry non-Jews?

Schwab: It was clear to the assembly sort of what the right answers were to these questions and a lot of their job was, how do we say what he wants, but in a way that is still authentic to us? For those first two, I think, it was pretty easy. They said, “Do Jews practice polygamy? It’s not outlawed in the Torah, but we really don’t practice it and there was a rabbi who ruled this a long time ago and we accept that now,” because Napoleon, he wanted the answer to be no, they don’t accept polygamy. The divorce thing, he wanted them to sort of say we follow French civil law, which is basically what they said of like the Torah allows it, but we should also as citizens of France follow French civil law.

Yael: Got it.

Schwab: The non-Jews question was a really thorny one for them to answer and the answer they came up with sort of tried to play both sides of it and that they said, “The Torah does not explicitly prohibit it, but the rabbis don’t really recognize it or wouldn’t really encourage it or facilitate it,” and then they threw this in there for good measure, they’re like, “Just the same way that probably Protestant or Catholic priests wouldn’t really want their people marrying Jews, that’s kind of how we see it, too.”

Yael: Because I’m thinking on the one hand, Napoleon might be wanting to hear that the Jews see themselves as Frenchmen first and are not going to make this distinction in marriage between the Jewish boy, who lives on one street and the French girl who lives on another. But at the same time, just because the Jews were emancipated doesn’t mean all of a sudden everyone loves Jews. I mean, we know very much that that’s not the case. I could also see the right answer being, yeah, we’re going to keep to ourselves and marry each other and you don’t have to worry about your women being defiled by us.

Schwab: Exactly. In some ways it’s a perfect answer because you’re right of what Napoleon wanted to hear was that you see themselves as Frenchmen and they were like, yeah, we do see ourselves as Frenchmen and just all the other Frenchmen, we still kind of want to marry within our own religion, the same way that everybody else does. We’re just like everybody else.

Yael: Jews, we’re just like you.

Schwab: Jews, we’re just like you only we don’t marry you. Then that, I guess let’s get to that next because there’s a series of questions about citizenship and that was one of them. Do Jews consider Frenchmen their brothers? Do Jews see themselves as Frenchmen and do they see their fellow French citizens as fellow citizens? And, do they have a double standard? This was a huge question. Can Jews treat non-Jews differently? Because Napoleon was familiar with this very common complaint and there were plenty of sources for it in the Talmud and he said, “It really seems like Jews are legally allowed by their own laws to treat their non-Jewish neighbors differently. They’re allowed perhaps to charge them interest that they wouldn’t be allowed to charge.” Usury got thrown around a lot and they were like, “Well, it’s not exactly Usury, that term is used a lot. That’s not really what’s going on here,” and they asserted that they do not have a different standard of treatment for Jews and non-Jews. The final question there was will Jews defend France in a war? Would Jews fight in the French army?-

Yael: I hope they said yes.

Schwab: Oh, it was a resounding, it was a very enthusiastic yes. It was something like we would gladly fight and die for France in a war-

Yael: Amazing.

Schwab: … they knew what the right answers were.

Yael: Once they answered Napoleon, so this was before he convened this Sanhedrin?

Schwab: Yeah. They write these answers and then they convene the Sanhedrin a year later to pass these answers into law and this felt like a really big deal at the time. First the assembly. And the fact that this many Jews from this number of different backgrounds and places in France and different communities all got together and agreed on something and sort of wrote this text of these answers that they all passed together. And then that it went to this Sanhedrin, which was also made up of all of these different Jews from different places, and the Sanhedrin passed these answers into law and disseminated them-

Yael: French law.

Schwab: Well, Jewish law, really, like they as the Sanhedrin, they ruled. Hey, I know we have the original Torah, the Bible, and the Talmud, and now we have a new addition, that’s how it was really, certainly that’s how Napoleon wanted it to be seen and there were a lot of people who saw it this way at the time of here is the next iteration of Jewish law that will be studied and memorized and dissected, which it was then. It was taught in French schools for a little bit of time after this.

Yael: But it’s Jewish law as shaped by the vision of Napoleon and what Napoleon wanted the Jews, what their community to look like and what he wanted them to be doing.

Schwab: Yeah. There was definitely an awareness of this is nobody was under threat, like it wasn’t Napoleon locked them in a room and threatened to execute them if they didn’t come up with these answers, but it was clear there are some, I don’t even know if coercion is the right word, but there’s definitely influence of it’s clear what the answers should be and what Napoleon wants them, but there’s also a desire on the part of the Jews to say, “We want to give these right answers because we want to become citizens of France and this is the path to that.”

Yael: Right. This is the first time in Jewish history that a nation state or municipality or whatever it is you want to call it, is actually open to the notion of the Jew being a full-fledged or almost full-fledged citizen.

Schwab: Mostly-fledged. That offer is on the table and the Jews wanted it. They took it. They wanted to become citizens of France because there were a lot of opportunities there.

Yael: I know Napoleon has been dead and gone for quite some time, but there are still Jews in France and is this legal construct still something that’s around?

Schwab: I don’t think so. I don’t think this is still, the Sanhedrin and the statements of the assembly of Jewish notables are still being taught in French schools. They’re like, okay, we finished our annual reading of the Torah, now it’s time to study the answers of whether Jews may marry non-Jews according to the Assembly of Jewish Notables. But there is a lasting impact of this sort of set the stage, not just in France, but in many countries for this model of saying here’s a Jewish path towards citizenship, here’s what it looks like when Jews become integrated. Once these answers are out there, people can build off of it and work off of it and Jewish communities become shaped by this also, to some extent.

And it’s a huge difference, I think, like you asked before about France today versus America today and a big difference between America and other places is it the separation of church and state is enshrined as an American value and it’s so strong. France and most other countries don’t have as fully developed that same idea and in many of them there can be even a legal construct of a religious leader, like the chief rabbi, and actually the idea of a chief rabbi is something that emerges from this.

Yael: Oh, interesting.

Schwab: We haven’t even gotten… Yeah, there’s a really interesting character. He is elected as president of the Assembly of Jewish Notables and the Sanhedrin, Rabbi David Sinzheim, look him up. He is a very dour-looking gentleman who wore an absolutely outrageous hat. You got to Google him, David Sinzheim, just so you can see a picture of this gigantic hat.

Yael: I feel like if you’re going to be a notable Jew, you got to get yourself a notable hat.

Schwab: His hat is definitely notable. I would put it on the list of most notable hats of history.

Yael: Was he scholarly or was he just like a well-known person?

Schwab: No, no, no, no. He was actually pretty scholarly and pretty big into this and actually gave up part of his scholarly career to basically then serve as the chief rabbi. He later lamented the fact that he had to spend a lot of his time in Paris, separated from his library of religious books, and he was never able to delve into Torah study the way he really wanted to because he was so busy in Paris in this sort of administrative position of what was not yet called, but eventually became the idea of having a chief rabbi, somebody who is connected to the government, but really speaks to and on behalf of the religious community of Jews in France. That model later moved on to other countries, too.

Yael: That probably, I mean, I don’t know how well it functioned, but to me it seems like it could function much better then than it could now. I mean, you did mention there were Ashkenazi communities and Sephardi communities, but I think aside from those distinctions, Jews were probably a lot more monolithic in their practice or the way they thought about religion and I could be wrong.

Schwab: Yeah, I would actually say, I think that we’re more denominational now and there’s certainly a greater variety of Judaisms now, but I don’t think they were that monolithic at the time. This was the time there was a movement called the Haskalah, which were this like enlightenment perspective of saying, “Let’s really start reforming the religion and moving away from the religion in some way.” This is when denominations began to start. At the same time, there were strong traditionalists who really said, “We should not be changing or doing anything different.” They definitely were not monolithic in practice and even in answering some of these questions, there were real debates about how to answer them because there were those who did feel like we can just say, “Yeah, it’s fine to marry non-Jews,” and there were those who felt we cannot countenance this in any way whatsoever and they had to come to this compromise answer.

Yael: The only reason we’re even able to have this discussion or even think about the fact that there was an enlightenment movement in Judaism or that we have all these denominations today is because these Jews were emancipated. You would never think about moving away from religion or certain types of observance if that was all that you had. When the Jews were not citizens, when they were not allowed to be part of society, when they were both metaphorically and geographically living on the fringes of society, then what would be the point of moving away or where would you even think about moving away from observance because you’re only among your own?

Schwab: Yeah. That’s sort of the interesting flip side of this whole thing of emancipation and the granting of Jews citizenship allowed them to move away from being Jews in the same sort of way. Once they became French, now they were no longer just Jews, who lived geographically in the area that’s ruled by the Kingdom of France, but they became French Jews. And this entire question that I know you and I have spoken about of like, are we Jewish Americans or are we American Jews? That question is only enabled when you have a right to citizenship and that’s sort of where it all comes from.

Yael: Yeah. That’s something that I grapple with a lot and I know that that’s a conversation that could take several hours to get through, but I never really thought about the fact that me sort of twiddling my thumbs and going through all this existential angst over whether or not I’m an American Jew or a Jewish American is only a question I can ask because I’m permitted to be an American. Whether I put that American first in the descriptor or second, if I wasn’t permitted to be an American, I wouldn’t be able to have all of this innate anxiety about where I fit in the world.

Schwab: The next time you feel that anxiety about your place in the world and what your identity is and who you are, think about the fact that Napoleon asked that question directly to a group of Jews whom he assembled and said, “What’s your deal? Are you Frenchmen? Do you see yourselves as Frenchmen or are you just Jews who are totally separate?”

Yael: I totally would’ve snuck into that assembly, would’ve been like a Yentl situation, where I wouldn’t have been able to keep myself out.

Schwab: Oh, yeah.

Yael: And-

Schwab: Sorry. I definitely should have said, when I said it was representative of all Jews and a broad swath, I should have clarified it was just men, though.

Yael: I work in finance, I assume that everything is just men. That’s really interesting. I knew nothing about this. I mean, I definitely studied the French Revolution in high school and actually even again in college in a really cool class called Reacting to the Past. It’s almost a role playing game in the form of a class. But I didn’t know any of this, like I’ve never heard anything about Napoleon assembling a Sanhedrin, Napoleon and the Jews-

Schwab: Neither had I. I taught history in high school briefly and I taught the French Revolution and didn’t know anything about this either. This story was, the whole story, and there’s so many details we didn’t even get to was so wild and just blew my mind. It’s definitely a really interesting question to us, but I think it’s a really interesting question and what you’re saying speaks to this, that it’s a really a quite interesting question to everyone, what the deal is with the Jews? It’s a question that a lot of people seem to have.

Yael: You should be careful how you phrase that.

Schwab: People want to know.

Yael: Questions about Jews have been thrown out in the past in slightly dangerous ways.

Schwab: Yeah, yeah.

Yael: Cool. Another astonishing story of Jewish history. Thank you for enlightening me on the Enlightenment.

Schwab: Yeah. I’m looking forward to what we’re going to talk about next time.

Yael: Me, too. It’ll be a great one, don’t worry.

CREDITS:

Thank you for listening to Jewish History Unpacked, a production of Unpacked, a division of OpenDor Media. If you liked this show, subscribe on your podcast app of choice, and give us five stars and write us a review on Apple Podcasts. Check out jewishunpacked.com for everything Unpacked-related, and subscribe to our other podcasts. And of course, check out our TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, YouTube and Twitter – just look for @JewishUnpacked. And, most importantly, be in touch with Yael and Schwab – write to us at jewishhistoryunpacked@jewishunpacked.com.

This episode was hosted by Jonathan Schwab and Yael Steiner. Our education lead is Dr. Henry Abramson. Audio was edited by Rob Pera and we’re produced by me, Rivky Stern. Thanks for listening. See you next week.