We’re Curious…

In October of 2020 Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg announced that the company is banning posts that deny or distort the Holocaust. The social media site will also start directing people to authoritative resources if they search for information on the subject. Twitter followed suit and confirmed it would also ban Holocaust denial posts.

The announcement is a significant reversal of Facebook’s earlier policy. In July 2018, in an interview with the tech website Recode, Zuckerberg said that he did not think Holocaust deniers were “intentionally” getting it wrong, and that offensive content should be protected as long as it does not call for harm or violence.

After facing criticism for these statements, he clarified: “I personally find Holocaust denial deeply offensive, and I absolutely didn’t intend to defend the intent of people who deny that.” He added: “I believe that often the best way to fight offensive bad speech is with good speech. Zuckerberg has also repeatedly said he does not want his company to be an arbiter of truth regarding what people say on the platform.

So, what changed that led Facebook to make this decision and reverse its longstanding policy? And will this actually help stop the spread of Holocaust denial and antisemitism?

What is the Role of Jewish Education in Combating Antisemitism?

Before we dive into this story, we wanted to address the critical role that we as Jewish educators have in making sure both Jews and non-Jews understand the history of the Holocaust. At a time when data shows an alarming lack of basic Holocaust knowledge among Millenials and Gen Z, when antisemitic incidents and violence have reached historic levels, and when there are fewer living Holocaust survivors to share their stories, this educational work is urgently needed.

In September 2020, the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany — a nonprofit organization that works to secure material compensation for Holocaust survivors — released a nationwide survey of American adults under 40 showing a lack of awareness of key historical facts:

- 63 percent of respondents did not know six million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust. Over half of those thought the toll was under two million.

- Although there were more than 40,000 camps and ghettos in Europe during World War II, nearly half of respondents could not name a single one.

- One in 10 respondents could not recall ever hearing the word “Holocaust” before.

- Approximately half of respondents had witnessed Holocaust denial or distortion on their social media feeds or elsewhere on the Internet.

Gideon Taylor, president of the Claims Conference, said the survey results are “shocking” and “saddening.” He added: “We need to understand why we aren’t doing better in educating a younger generation about the Holocaust and the lessons of the past. This needs to serve as a wake-up call to us all.”

This data is clearly a wake-up call for us as educators. We need to make sure our students not only know basic facts about the Nazi genocide, but also understand the nature of antisemitism in history as well as how it appears today.

According to Deborah Lipstadt, a professor of modern Jewish history and Holocaust studies at Emory University in Atlanta, learning the history of the Holocaust is “not simply learning about the past. These lessons remain relevant today in order to understand not only anti-Semitism, but also all the other ‘isms’ of society. There is real danger to letting them fade.”

In her 2017 TED Talk, Lipstadt tells the story of her research into Holocaust deniers. She found that some Holocaust deniers parade as respectful academics, calling themselves “revisionist” historians. But beneath the surface, they had the same adulation of Hitler and antisemitic and racist beliefs as neo-Nazis. She concludes that “deniers are neo-Nazis without garb,” and offers the following takeaway: “We cannot be beguiled by rational appearances. We’ve got to look underneath, and we will find there the extremism.”

This is exactly the kind of education we can give our students: to empower them to recognize and speak out against Holocaust denial — and all forms of bigotry — when they witness it, whether online or offline.

At Unpacked for Educators, we have long stressed the importance of knowing our own story, but particularly when it comes to the Holocaust and antisemitism, our educational efforts cannot end there. Jewish educational institutions have a responsibility not only to make sure young Jews learn about the Holocaust, but that the non-Jewish world understands this history as well.

Why is this critical? First, because education is the most powerful and reliable tool we have to prevent hate. The 12th-century Muslim philosopher Ibn Rushd (Averroes) put it succinctly: “Ignorance leads to fear. Fear leads to hatred. Hatred leads to violence.” To help ensure a future where there is less antisemitism and bigotry of all forms, we need to invest more in Holocaust education for the non-Jewish world.

Second, we need to make sure the non-Jewish world knows this history because studies show that Holocaust education not only conveys knowledge, but also helps cultivate more empathetic, tolerant, confident and engaged students. A survey conducted by Echoes & Reflections — a Holocaust education program in partnership with the Anti-Defamation League, the USC Shoah Foundation at the University of Southern California and Yad Vashem — found that students with Holocaust education were more willing to challenge incorrect or biased information and stand up to negative stereotyping.

Finally, education can be an effective strategy not just in preventing hate in the future, but also in responding to people who have these attitudes and are ignorant about the Holocaust. Experts say that education is critical to helping young people distance themselves from violent extremism and resist recruitment tactics used by these groups. We believe that for those who are open to learning, hateful beliefs can be overcome through high-quality education. Our team is currently working on new videos and resources on antisemitism and the Holocaust, and we’ll be releasing them the beginning of 2021.

Facebook’s Announcement

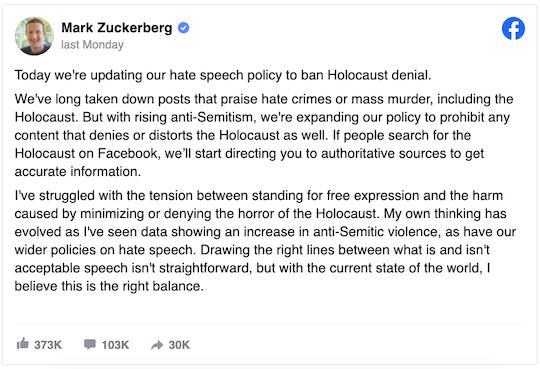

In his Facebook post announcing the change, Zuckerberg said that he has struggled with balancing free speech and the harm caused by denying the Holocaust, but that his thinking has “evolved” because of data showing an increase in antisemitic violence. He acknowledged that “drawing the right lines between what is and isn’t acceptable speech isn’t straightforward,” but concluded, “…with the current state of the world, I believe this is the right balance.”

In a blog post about the policy change, Monika Bickert, Facebook’s vice president of content policy, cited a recent survey that found that almost a quarter of American adults ages 18 to 39 said they believed the Holocaust was a myth, or that it had been exaggerated, or that they weren’t sure.

She wrote that the change “marks another step in our effort to fight hate on our services.” In addition to banning Holocaust denial content, Facebook has also banned more than 250 white supremacist organizations and accounts associated with QAnon and militia groups, and has removed 22.5 million pieces of hate speech in the second quarter of this year.

Bickert said the company worked with the World Jewish Congress, the American Jewish Committee, the Community Security Trust and the Simon Wiesenthal Center to understand how to combat antisemitism and how it is expressed online.

The company said it will immediately begin implementing the policy on Facebook and Instagram, which it owns, but that it will take some time to train their employees and technical systems before all Holocaust denial content is removed from the platforms.

The #NoDenyingIt and “Stop Hate for Profit” Campaigns

In recent months, Facebook has been under external pressure from Holocaust survivors, businesses and civil rights organizations to remove this content and do more to combat hate and misinformation in general on its platform.

In July 2020, the Claims Conference launched a campaign to urge Zuckerberg to remove Holocaust denial posts. The campaign used Facebook to share videos of survivors making personal appeals to Zuckerberg under the hashtag #NoDenyingIt.

Roman Kent, who survived various concentration camps, including Auschwitz, said: “Most of my family was murdered as well as many of my friends… You must know that Holocaust denial is nothing short of a hate dialogue. There is no denying it.”

Eva Diamant Szepesi said: “I was deported from Hungary to Auschwitz in 1944 when I was 12 years old. My mother, my father and my little brother Thomas were murdered by the Nazis…This is my story, there is no denying it.”

Adding to these testimonials, more than 1,000 businesses also pressured Facebook to “stop valuing profits over hate, bigotry, racism, antisemitism, and disinformation” through an advertising boycott. Led by the Anti-Defamation League, the NAACP and other civil rights organizations, the “Stop Hate for Profit” campaign prompted these companies — including Starbucks, Coca-Cola and Ben & Jerry’s — to pull their ads on Facebook for the month of July. Nearly two dozen celebrities — including Sacha Baron Cohen, Katy Perry and Kim Kardashian — also participated in an Instagram freeze coordinated by the campaign.

Reactions From the Jewish World

Leaders and organizations from across the Jewish world welcomed Facebook’s announcement, though some said the policy change was long overdue.

Jonathan Greenblatt, CEO of the Anti-Defamation League, said on Twitter: “This has been years in the making. Having personally engaged with Facebook on the issue, I can attest the ban on Holocaust Denial is a big deal. Whether it’s ADL & #StopHateForProfit’s insistence, #NoDenyingIt- it doesn’t matter. Glad it finally happened.”

The ADL has been calling on Facebook to change its policies to classify Holocaust denial on its platform as a form of hate speech since 2011, according to a statement from the organization. The organization tracked more antisemitic incidents in the U.S. in 2019 than at any other point in the past 40 years.

Several Jewish institutions responded by pointing out the distinction between antisemitic hate speech and acceptable free speech. The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum said: “Freedom of speech is vital to our democracy, but it does not require any organization to host antisemitic speech that can potentially foment violence.”

Rabbis Marvin Hier and Abraham Cooper, leaders of the Simon Wiesenthal Center, said: “Denying the Holocaust has never been about free speech, but only as a tool for genocide-seeking Iran, neo-Nazis and bigots to demean the dead and threaten the living.” And Yad Vashem said: “Holocaust denial and distortion are forms of antisemitism and should be classified as hate speech.”

Israeli opposition leader Yair Lapid responded on Twitter to Zuckerman’s post: “I commend Facebook for making the right decision. Holocaust denial is an expression of the lowest strain of antisemitism that needs to pass from the world and the internet.”

Censorship vs. Counterspeech: Which Approach Is Best?

Although the Jewish world overwhelmingly viewed this announcement as a positive change, not everyone agrees with the idea that censoring hateful content is a good idea.

Nadine Strossen, the former president of the American Civil Liberties Union and the daughter of a Holocaust survivor, argues that censoring content can backfire and that we should be more focused on engaging in “counterspeech.” This approach seeks to counter ideas of hatred and discrimination by providing “affirmative information” and education. Strossen notes that during the Weimar Republic (Germany’s government leading up to the rise of the Nazi party), there were very strict anti-hate speech laws; these were then used as Nazi propaganda tactics.

Yair Rosenberg, a senior writer at Tablet Magazine, made a similar argument, in July 2018, after Zuckerberg said that Holocaust deniers were not “intentionally” getting it wrong. In an op-ed published in the Atlantic, Rosenberg criticized Facebook for not acting to combat Holocaust denial and other forms of bigotry on their platform, but argued that “censorship is not an effective response to internet anti-Semitism and racism.” Like Strossen, he made the case that censoring hateful content can have the unintended effect of drawing more attention to those individuals and ideas. He also argued that removing all evidence of hate online would lead to overlooking prejudice problems in society, and advocated for a “counterspeech” approach.

On the other side of the debate, Dan Shefet, president of the Association for Accountability and Internet Democracy, argues that people should be held accountable for their speech online through censorship. In a recent debate with Strossen, hosted by the American Jewish Committee, Shefet emphasized the power of words and how hateful ideas online incite real-world violence. He also argued that while counterspeech may have been an effective strategy in the past, this approach will not work in today’s age of social media, where we see curated feeds of individuals and ideas that are likely to reinforce our existing views.

In November 2019, Sacha Baron Cohen, speaking at the ADL’s annual “Never is Now” conference, argued in favor of restricting hate speech online and criticized Facebook and other social media sites for not taking down Holocaust denial content. “This is not about limiting anyone’s free speech, this is about giving people, including some of the most reprehensible people on earth, the biggest platform in history to reach a third of the planet,” he said. Tech companies should not give racists, misogynists, antisemites and other bigoted people “a free platform to amplify their views and target their victims.”

How does all of this apply to Facebook, Twitter and other social media companies? Facebook’s new policy includes both “censorship” and “counterspeech” tactics: It removes Holocaust denial content (censorship) and directs people searching for information on the subject to credible sources (more of a “counterspeech” approach). In May 2020, Twitter engaged in “counterspeech” when it began annotating “potentially harmful and misleading content” with messages that provide fact-checking and additional context.

Will banning this content from Facebook and Twitter be effective in combating the spread of Holocaust denial and antisemitism? Time will tell both how this plays out and what steps Facebook, Twitter and other social media companies will take next.

The Bottom Line

In a dramatic reversal of its earlier policy, Facebook is taking a stand against Holocaust denial and distortion. Twitter is also removing this content. The survivors’ #NoDenyingIt campaign; the “Stop Hate for Profit” advertising boycott; data showing that ignorance about the Holocaust is rising; and discussions between Facebook and Jewish organizations may have each contributed to this decision. Leaders and organizations from across the Jewish world welcomed Facebook’s announcement as an important step at a time of rising antisemitism around the world. At the same time, there is a debate about how to tackle the problem of hateful speech: Should we be censoring content or engaging in counterspeech? Particularly at a time when data shows a lack of Holocaust knowledge among Millenials and Gen Z, Jewish educators and institutions have a critical role to play in educating both Jews and non-Jews about the Holocaust.

Originally Published Oct 19, 2020 08:23AM EDT