Editor’s note: This is part 5 of a multipart series. You can view the entire series here.

In October 2017, ex-CIA agent and noted leftist anti-war activist Valerie Plame shared an article from an antisemitic web site with her 50,000 Twitter followers. Its title: “America’s Jews are driving America’s wars.”

As outrage mounted, Plame defended her choice by noting “I am of Jewish descent,” an apparent reference to her single Jewish grandparent.

On the surface, this sounds like a compelling case. After all, can a Jew, or someone with Jewish heritage, really be antisemitic–or say antisemitic things?

As it turns out, yes.

To understand how, we’ve got to go all the way back to the Middle Ages to someone you’ve probably never heard of.

In 1238, a Jewish apostate named Nicholas Donin traveled to Rome and personally denounced the Talmud as anti-Christian to Pope Gregory IX. This set in motion a chain of events that led to the largest mass burning of the Talmud in recorded history, with some 10 to 12 thousand volumes of the foundational Jewish work set ablaze in France. This was before the advent of the printing press, and these books were all handwritten and irreplaceable. The event was so traumatic that for hundreds of years on Tisha B’av, the national Jewish day of mourning, observant Jews have recited a haunting prayer commemorating the tragedy.

And this all happened because of a Jew.

Sadly to say, Donin’s story is not unique. Historically, Jews have excelled at many things, including antisemitism. This can seem counterintuitive at first glance, but it is also quite well documented—and one doesn’t have to go back to the 13th century to find it.

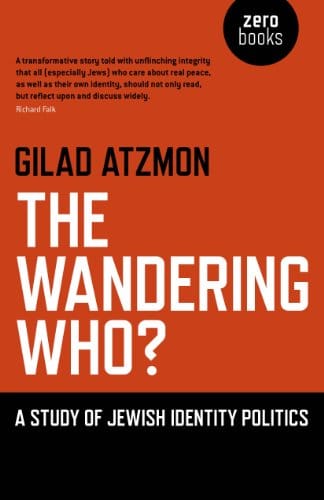

Take Gilad Atzmon, a noted Israeli musician and activist living in London today. In 2011, he published a book called “The Wandering Who? A Study of Jewish Identity Politics.” It’s a cartoonishly antisemitic tract. In it, Atzmon dubs American Jews “the enemy within,” questions the historical facts of the Holocaust, and claims that “robbery and hatred” are inherent to Jewish political ideology. Atzmon has also compiled lists of suspect Jews in the U.S. government and declared, “we must begin to take the accusation that the Jewish people are trying to control the world very seriously.”

Consider another British personality, Jackie Walker. As a leader of the powerful leftist political group Momentum, Walker was instrumental in consolidating power for Jeremy Corbyn, the former British Labour party leader from 2015 to 2020. Her work was even spotlighted in the New York Times.

She also labeled Jews the “chief financiers” of the African slave trade—a libel long debunked by historians. When confronted with the facts, Walker not only refused to apologize, but insisted she could not be antisemitic because she possessed Jewish heritage. She subsequently questioned whether Jewish schools needed additional security protection and criticized Britain’s Holocaust Memorial Day.

This phenomenon of Jewish antisemitism is not limited to one part of the political spectrum. In 2016, in the heat of the U.S. presidential campaign, Joshua Seidel wrote an op-ed for the Jewish newspaper The Forward titled “I’m a Jew and I’m a Member of the Alt-Right.” In it, he defended the typical anti-Jewish rhetoric often heard from this openly antisemitic part of America’s political spectrum.

Even the son of Israel’s prime minister once shared an antisemitic cartoon about a Jewish conspiracy that was then championed by white supremacist David Duke!

Here’s the thing: While all of these individuals cite their heritage as a shield against accusations of anti-Jewish animus, that is a distraction, not an argument. Racism is racism no matter who says it. It is the substance of bigotry that matters, not the source.

So why do some Jews do this?

In general, there seem to be two chief motivations behind such behavior.

The first is that minorities often absorb stereotypes about themselves from the majority. When everyone around you shares certain assumptions about your community, it can be easy to subconsciously accept them. This is how Karl Marx, who was ethnically Jewish but whose father converted to Christianity, could write things like “What is the worldly religion of the Jew? Huckstering. What is his worldly God? Money.”

Scholars call this “internalized racism,” and it’s something many Jews and other minorities have experienced. Because of this, a Jew might say something antisemitic, but this doesn’t mean they’re an antisemite with a worldview grounded in anti-Jewish ideas.

More insidious are those Jews who adopt the assumptions of antisemites wholesale and make them their political program. For these individuals, antisemitism is a punch card to power in places where their community is despised and ostracized. By separating themselves from most other Jews, and justifying prejudice towards them, these people hope to insulate themselves from antisemitism, and obtain influence among growing political movements that are otherwise hostile to Jews. By throwing other Jews under the anti-Jewish bus, they hope to save themselves from it.

For this reason, Donin sought to prove his Christian cred by denouncing the Talmud to the Church. Joshua Seidel attempted to insinuate himself into the alt-right by defending their anti-Jewish conduct. And Jackie Walker aimed to access the elite of the British Labour party–which was later found by a government watchdog to have engaged in widespread anti-Semitic conduct–by repeating and defending antisemitic ideas.

Then theyr surprised Jews have reputation 4being sleazy thieves. #apartheidisrael doesn't need or deserve these $$ https://t.co/5DGjBmTDMN

— Miko Peled (@mikopeled) September 14, 2016

But the truth is, nothing about these people’s Jewish background makes their words or actions less reprehensible. When Miko Peled, an anti-Israel activist and son of an Israeli general, justified calling Jews “sleazy thieves,” the fact that he was Jewish did not make the stereotype any less racist. And when Plame tweeted that “America’s Jews are driving America’s wars,” her claim of “Jewish descent” did not make it any less bigoted.

Whether a Jew engages in antisemitism for ideological or psychological reasons, the end result is the same—and should never be excused.