One of the many things that has set “Bridgerton” apart is its colorblind casting, which challenges the traditional norms of whiteness that have typically defined the regency romance genre.

Regency-period romances, set between 1810-1820 during Prince George IV‘s tenure as Prince Regent, are a major subset of historical romance novels, primarily focusing on the upper-class marriage market in London, known as “the ton.”

While the show has received praise for featuring actors of color as members of the aristocracy, it has also faced criticism for not addressing issues of race and the discrimination faced by marginalized identities during the period.

This is notable because the author of the Bridgerton novels, Julia Quinn, is Jewish, yet the series lacks Jewish representation and makes no mention of Judaism.

The unfortunate truth is that the ritzy lives of the upper-class gentry depicted in historical romances were typically exclusive to white, Christian members of society. To be granted a title, one had to be Christian, and to vote, one had to be a white, land-owning Englishman.

To this day, there has never been a line of Jewish lords in England — Jews like Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks have been appointed as a “life peer” in the House of Lords, meaning he was awarded a title for his service, but it could not be inherited.

However, there was a large Jewish presence in Georgian England whose lives were just as colorful and interesting as the characters in “Bridgerton.” Let’s unpack what it meant to be Jewish in England during the Regency period.

Jews in Georgian England lacked the rights of their Christian counterparts

Jews were banished from England between 1290 and the 1650s, but many returned to England after the ban was lifted, attracted by the relatively lower levels of antisemitic violence compared to other parts of Europe. However, the Georgian Jews of England still faced significant antisemitic prejudice.

During this period, Jews were not granted the right to vote, until 1858. The lack of legal emancipation prevented Jews from being fully accepted in society and hindered their access to various parts of civil life.

Without emancipation, Jews could not vote, hold public office, or take commission in the British military, as all of these required taking an Anglican oath, which Jews were barred from doing.

There was an attempt to legalize Jewish Brits with the Jewish Naturalization Act of 1753, but it was quickly repealed within a few months due to heavy pushback.

Life for Sephardic vs. Ashkenazi Jews in Georgian England

Sephardic Jews in Georgian England had an easier time integrating into the upper classes compared to the newly arrived Ashkenazi Jews, who were often less educated and poorer.

Many Sephardic Jews had adopted more secular practices, partly because they descended from Conversos — Jews who were forced to convert to Christianity and conform to Spanish or Portuguese culture during the Spanish Inquisition.

Additionally, many Sephardic Jews had immigrated to England from the Netherlands, where they had sought refuge during the Spanish Inquisition. The Jewish community in the Netherlands was heavily involved in the trade industry, which provided them with greater access to foreign goods and travel and, in turn, more exposure to European culture compared to the more isolated Ashkenazi community.

Working-class Ashkenazi Jews often chose to speak Yiddish among themselves, which was criticized by their wealthier peers. Middle- and upper-class Jews, on the other hand, adopted English entirely, speaking it in their homes and converting synagogue records from Yiddish to English and Hebrew.

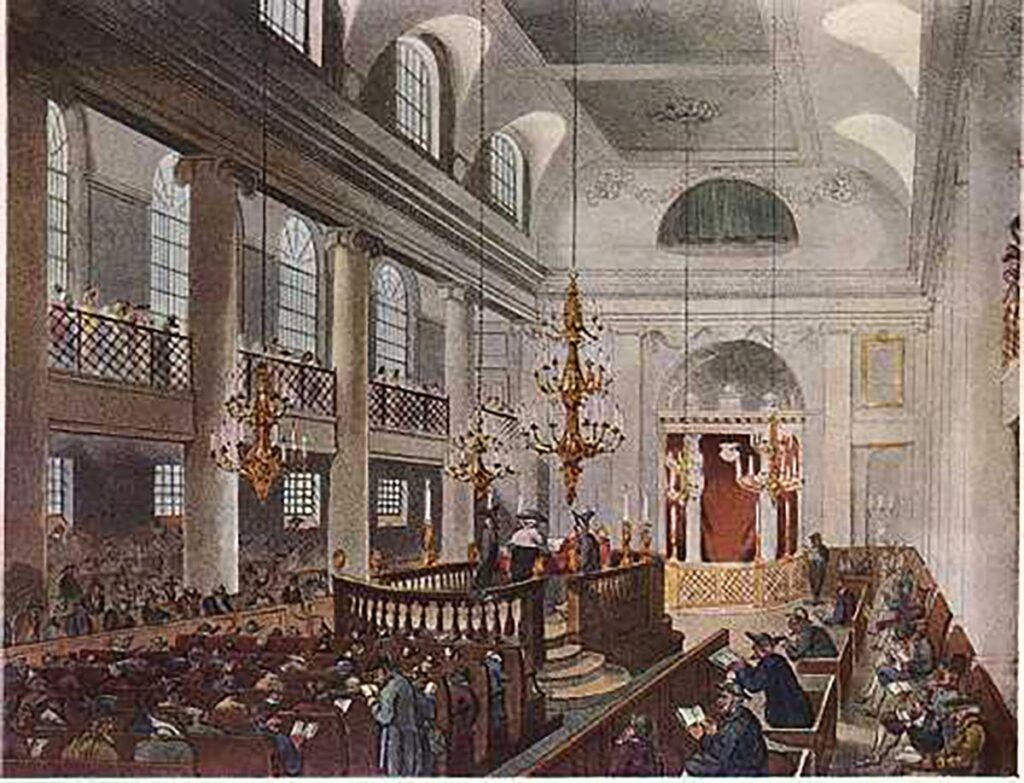

The Great Synagogue of London even decided to make announcements only in English; this move was controversial as many working-class Jews and new immigrants only spoke Yiddish and could not understand the announcements.

Antisemitic conspiracies in Georgian England

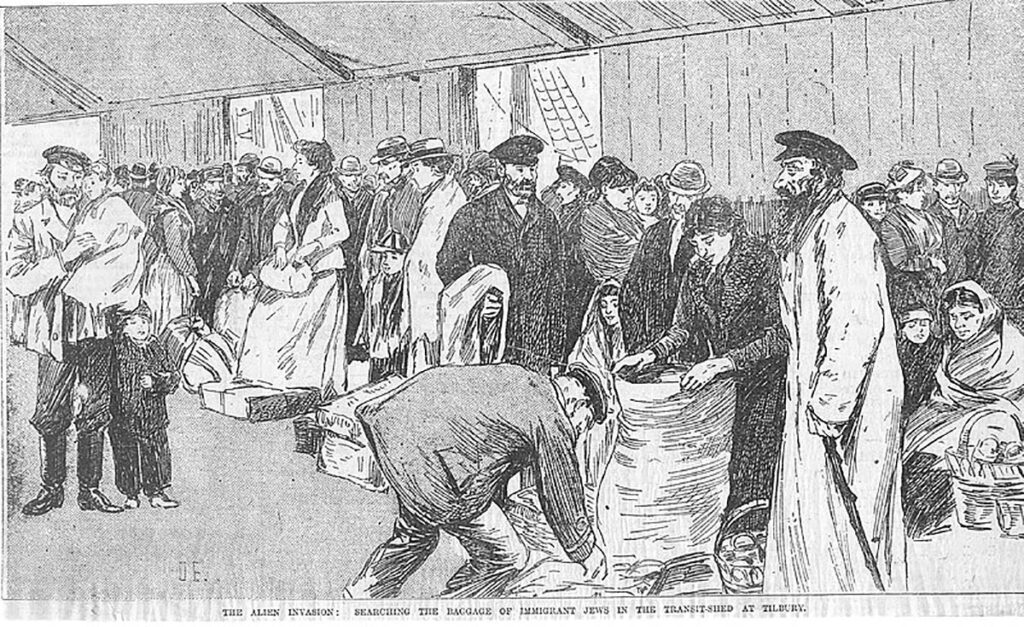

Similar to the antisemitic backlash spurred by Ashkenazi immigration in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in the United Kingdom and United States, this earlier wave of Eastern European migration increased the ostracization experienced by Jews.

In Georgian England, antisemitism was deeply ingrained in society, with Jews often stereotyped as dishonest and untrustworthy.

German tourist Karl Philipp Moritz observed during his 1782 visit that antipathy towards Jews was pervasive, with even casual conversations reflecting deeply rooted prejudices. Jews were frequently scapegoated for various societal issues, and their loyalty and integrity were commonly questioned.

Many believed that Jews were loyal only to themselves, but could adapt to any environment — an idea the Nazis later dubbed “rootless cosmopolitanism.”

The media played a role in perpetuating these stereotypes, often overreporting negative behavior by Jews. Financial crimes committed by Jews would frequently become national news.

This “casual” form of antisemitism affected all social classes, shaping the perception and treatment of Jews during the Regency period.

There were many Jews who lived lavishly like the Bridgertons

While most Jews in Regency England lived and married within the Jewish community, there were many who strived to join Anglo high society.

Those who were wealthy and willing to suppress or hide their Jewish identity were sometimes accepted into the ton. They attended the same parties, had their portraits painted by renowned artists, and played cards at the same clubs as the aristocracy depicted in romance novels.

Upper-class Jews could earn societal prestige based on the grandeur of their parties, their wealth, and their degree of assimilation. To climb the social ladder, many adopted British clothing styles, donated to Christian charities, embraced British customs and manners and abandoned kosher dietary laws.

A significant number of Jews converted to Christianity, with some continuing to practice Judaism privately or anonymously donating to synagogues and other Jewish causes. Others fully embraced Anglicanism. These conversions were often widely publicized in the news and discussed across the country.

Wealthier Jews who were not part of the ton’s social circle held their own balls within their community, often situating balls around Jewish holidays.

Two of London’s largest synagogues banned noisemakers on Purim, considering the raucous tradition to be improper and not sufficiently Anglicanized.

To join the upper echelons of London society, many Jews in the Regency period sought to obtain one of the 12 stockbroker licenses available to Jews, which enabled them to participate in trading at the London Stock Exchange.

There was stiff competition for the licenses, and the Lord Mayor of London would charge a large fee for nominating someone for the position. For example, the uncle of Moses Montefiore, a prominent British financier and former Sheriff of London, paid £1,200 (equivalent to $170,000 USD in 2024) for a license for his nephew.

However, many Jews also traded stocks as unlicensed brokers.

Unlike members of the ton, whose wealth came from managing their estates, the Jewish upper class had to work and could not spend much time away from major cities. However, to be more like nobility, wealthy Jews began purchasing small estates outside the city for their wives and children to live in.

Intermarriage and a shift toward less strict religious observance

During the Regency period, intermarriage within the Jewish community became more common. There were instances of Jews converting to Christianity, and vice versa, to facilitate advantageous marriages.

The Marriage Act of 1753 mandated that Christian marriages be conducted in a religious ceremony, effectively banning elopements. This law required one member of an interfaith couple to convert for their marriage to be legally recognized, as marriages had to be performed in a church to be considered valid.

As a result, Jewish weddings, or weddings where the Jewish partner did not convert, were not legally binding.

Many Jewish men who married non-Jewish women continued to maintain public Jewish lives. They remained active members of their synagogues, were called to the Torah, arranged circumcisions for their sons with unauthorized mohilim (since the son was not considered Jewish according to halakha without a Jewish mother), and were buried in Jewish cemeteries.

Contrary to trends in other parts of Europe where Jewish communities were becoming more religious, the Jewish community in England followed the lead of the Christian community and became more secularized.

The influence of the Enlightenment

Influenced by the Enlightenment and the development of cosmopolitan cities, people began to practice religion less strictly than their ancestors. There was a noticeable decline in adherence to Orthodox Judaism and observance of many mitzvot, such as keeping kosher, attending synagogue and observing the Sabbath.

In his book “The Jews of Georgian England,” Anglo-Jewish history scholar Todd Endelman linked the decline in religious observance to the rise of a capitalist economy in England.

“Religion ceased to be a matter of overriding interest for Englishmen, in part because the commercially expansive material culture of England was not conducive to the cultivation of purely spiritual concerns,” he wrote.

Scholars also attribute the decline in religious observance to the general influence of the Enlightenment, cultural assimilation, and the desire to integrate into English society amid the changing legal and social landscape of the times.

Secular Jews also sought to ensure that their fashion choices reflected their declining religious observance. In terms of external appearance, most Jews were indistinguishable from Englishmen, as the men abandoned traditional religious beards, married women stopped covering their hair, and both adopted the latest fashion trends.

Many Jews were prominent figures in Georgian England

During the Regency period, several of the top boxers — the most popular sport of the period — were Jewish.

Daniel Mendoza, a Sephardic Jew, revolutionized boxing during his stint as a professional boxer and the head of a London boxing school. Mendoza became famous for his “scientific style,” which encouraged boxers to move around the ring, a departure from the previous stand-and-punch approach.

Benjamin Disraeli, a Sephardic Jew who converted to Anglicanism, later served as the Prime Minister of the U.K. in 1868 and 1874.

In the finance industry, many Jewish individuals became influential and integrated into English society.

Benjamin Goldsmid, a government loan contractor, was accepted as a peer by the ton and even dined with the King and Queen.

The Rothschild family rose to prominence during the Regency period. Nathan Mayer von Rothschild established Rothschild & Sons bank in London in 1811, following his father Mayer Amschel Rothschild’s directive to expand the family’s influence in England.

The Rothschild family’s significant contributions — such as financing the British government’s purchase of the Suez Canal and supporting the Duke of Wellington during the Napoleonic Wars — underscored their prominent role in shaping the economic landscape of Georgian England.

Regency Jews created the foundation for modern Jewish life

In many ways, Regency Jews laid the groundwork for modern Jewish life, initiating a process of social integration and a shift towards less strict religious observance that has characterized many Jewish communities in the U.K. and the U.S. since that era.

While “Bridgerton’s” inclusive casting is a step forward in diversifying Regency stories, the absence of Jewish characters in the series is a missed opportunity to reflect what life in Georgian England really looked like.

Including Jewish narratives in historical dramas would not only honor the contributions and struggles of Jews during this period but would also enrich the storytelling by embracing the full spectrum of historical experiences.

Read more: 8 of the British royal family’s most fascinating historical Jewish connections