Schwab: Welcome to Jewish History Nerds, where we do exactly what it sounds like. Nerd out on awesome stories in Jewish history.

Yael: I’m Yael Steiner, and my childhood dream was to stay in school forever.

Schwab: I’m Jonathan Schwab, and I am in school forever.

Yael: Schwab, I am excited to hear from you this week about a topic that I think I know nothing about.

Schwab: Yes. We were just discussing right before the recording about this topic, we’ll be talking about the Talmud, but also, a gentleman by the name of Johannes Eisenmenger.

Yael: I didn’t even know if it was a name when you said it. It was just a lot of syllables.

Schwab: That’s a guy, it’s a Germanish name, and he’s living in the late 1600s, early 1700s. But before we get to him, I think we have to talk about the Talmud and about how it plays into this whole story. And I actually wanted to start with… It’s sort of a joke, sort of a personal story. It was memorable and funny at the time, and I actually think really relates to what we’re talking about.

My brother, shortly after he got married and graduated college, he and his wife decided that they would spend the first year of their marriage in Israel, where he was studying primarily Talmud, full time, in a yeshiva. And I was visiting them in Israel when I was with them at one of our cousins, who’s a somewhat snarky fellow-

Yael: Must run in the family.

Schwab: Yeah (laughs). My brother, has a similar sense of humor in many ways. So this cousin of ours said to him, “Oh, you’re spending a lot of time studying the Talmud, and you’re recently married. Do you know that it says something along the lines of, ‘if you follow the advice of your wife, you’re destined to fail at everything.'” And my brother responded, “Well, it says a lot of things in the Talmud, including that at night, the sun travels underneath the Earth through a series of tunnels so it can come out the other side and rise again the next morning.”

And this is a line that I’ve used many, many times. Any time anyone references something that it says in the Talmud, I almost immediately say, “well, it says a lot of things in the Talmud,” Not every single thing that’s ever said in the Talmud necessarily bears the same weight, or should be treated the same way as this is, you know, like proscriptive. Or even more importantly, this is the Jewish position on something.

Yael: I totally agree with that, but I think the real moral of your brother’s story is happy wife, happy life. Even if it says the opposite in the Talmud, because as you say, the Talmud says a lot of things.

Schwab: You know what? Among the many things that the Talmud says, on almost every single issue, I’m sure that it also says the opposite of that.

Yael: A hundred percent.

Schwab: Like, the same way that sun thing that I referenced, that’s part of a long discussion where the rabbis are arguing about how they think that it actually does work, and there are a number of different theories given, you know, for what does happen to the sun at night? I don’t think any of which were a heliocentric model of the universe.

Yael: That was a couple of hundred years away.

Schwab: Yeah. They were a little too early for that. Most importantly, yeah, the Talmud does say a lot of things.

Yael: Just to clarify for some of our listeners who may not be as familiar with the learning of the Talmud, the Talmud is an analysis of the Torah text in two different forms. First, the Mishnah, which was the original analysis of the Torah text, and then the Gemara, which is an analysis of the Mishnah, and a real study of what the various positions in the Mishnah are meant to reflect. I don’t know if that makes it easier to understand or harder to understand.

Schwab: Yeah, you know, Nerd Nation is a very diverse group, and there might be people who study the Talmud extensively, and there might be some who don’t know that much about the Talmud. So without spending an entire episode on it, yes to everything you just said. I think the two other really important elements to add are, oftentimes people who don’t know that much about it think, “okay, the Talmud is the list of rabbinic laws.” The Talmud is a lot more than just the actual law. It’s a lot of discussion, different positions, positions that are rejected very often, and sort of the analytical process by which the rabbis who are arguing come to those positions. And it’s written as this back and forth dialogue between these different positions.

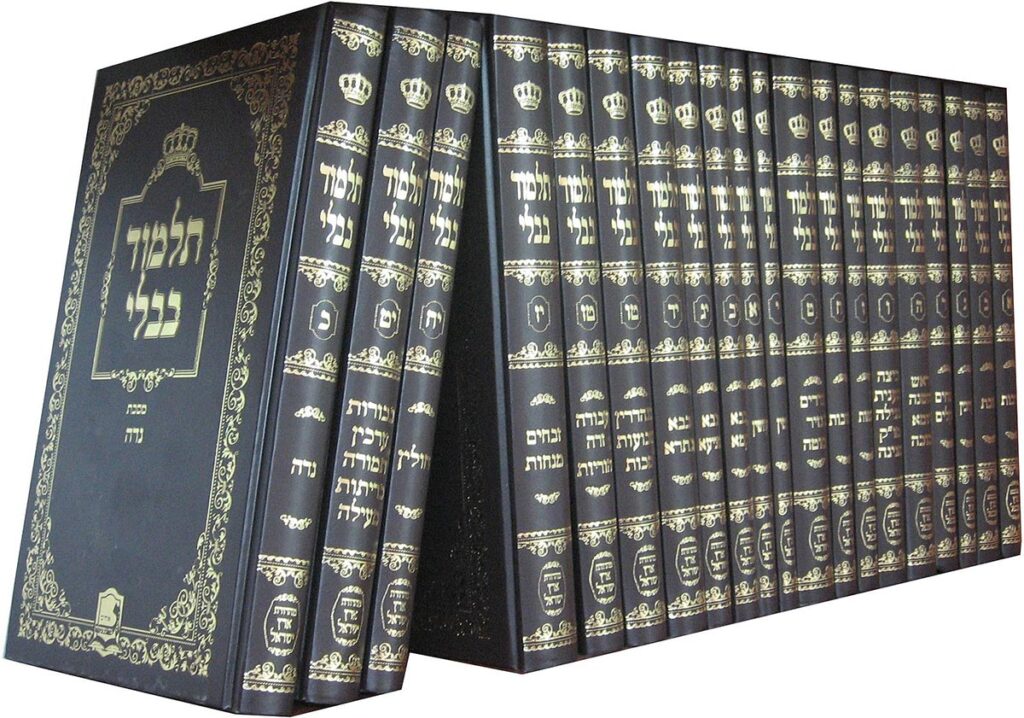

And the other really important thing is, the Talmud is absolutely massive. We’re talking about a huge, huge, huge work. It’s split up into dozens of books, it’s thousands of pages long. So we’re talking about a simply massive text, and due to the nature of its structure and the sort of back and forth conversation, also the fact that it’s written in a very obscure language, Aramaic, which is Hebrew letters but it’s not Hebrew. You really need to sort of learn this additional other language, that’s just for Talmud, Talmudic Aramaic. And it’s commented printed with no punctuation, ’cause we gotta make it even more fun. And to understand any of what it’s saying, you have to really be familiar with the flow of how text works in the Talmud. There’s no other text that works like this in any way.

Yael: It’s an extremely complicated text and it takes years and years and years to even come close to mastering it. It is not something that you can easily pick up on your own-

Schwab: Correct.

Yael: And for most of Jewish history, it was really the exclusive domain of the learned. Luckily for us, in the past few decades, there have been publishers that have brought the Talmud to the masses by providing translations and analyses in various languages. English, plain Hebrew, in Russian, et cetera. So A lot more people learn Talmud now than ever before. I don’t know if that’s relevant to the story or where we’re going.

Schwab: The first part you said is super relevant, and I’m so glad you said it. For most of Jewish history, this is something that was accessible only to a really elite and learned few, because of just the amount of time and effort you would have to put into training yourself in all of this. Even once it started being printed, after the advent of the printing press, even if you could get your hand on a copy of the Talmud, it wouldn’t make any sense to you unless you had really spent years of study, to be able to penetrate it in any way.

And that’s the story we’re gonna tell today, about a person who did not come from that background, but did devote years of his life to being able to understand what it was that the Talmud was saying.

Yael: That’s Johannes.

Schwab: Johannes Eisenmenger. He’s not born Jewish. He, at the age of 24… This is in 1680 and this is primarily in Lithuania, among a number of other places… He comes to the Jewish communities and says, “I wanna convert to Judaism, and I really want to learn the Talmud.” And he converts, he marries a Jewish wife, he has a number of Jewish children, and he spends years of study alongside and under various sorts of rabbis and other Jews so that he really can understand what the Talmud is saying. He spends 19 years.

Yael: How had he even heard of the Talmud?

Schwab: Christians, they didn’t know often what was in it. But they certainly knew there was such a thing as the Talmud. There had been a number of things previously, where Christians, and very often Jewish converts to Christianity, would bring to the attention of the church, some of the things that were said in the Talmud, which we’ll get into a little bit later. So Christians were aware of the Talmud, and there’s sort of this Christian skepticism towards the Talmud, or worry that there’s something really bad about it.

One of the earlier people who was sort of very anti-Talmudic was a guy named Nicholas Donin. he was Jewish and converted to Christianity, but he brings up, “this is the biggest problem that Christians have with converting more Jews to Christianity, is they have this text called the Talmud, all of our arguments keep falling flat because of the stuff they’re seeing in the Talmud. We need to find a way to put a stop to the Talmud so we can convert more of them.”

And that’s the beginning of this tradition of, “oh, there’s a lot of anti-Christian blasphemy, and there’s other sorts of stuff in the Talmud.” And the church started censoring the Talmud, portions of the Talmud, but it still, for most people, even to the learned members of the church, they have an idea of what they think is going on in there, but they don’t really know what it’s saying, you know, page by page, what’s really happening in the Talmud.

Yael: They can’t even read what they think might be an attack on them, because it’s in Aramaic.

Schwab: Yeah, right. And there are no published translations, at this point, in the late 1600s. So like, really the only people who have this text are the Jews. And a very small subset of the Jews. Um, so Eisenmenger, after 19 years of studying the Talmud, turns out it was not really with the most positive intentions all along.

Yael: He was running a long-con for 19 years?

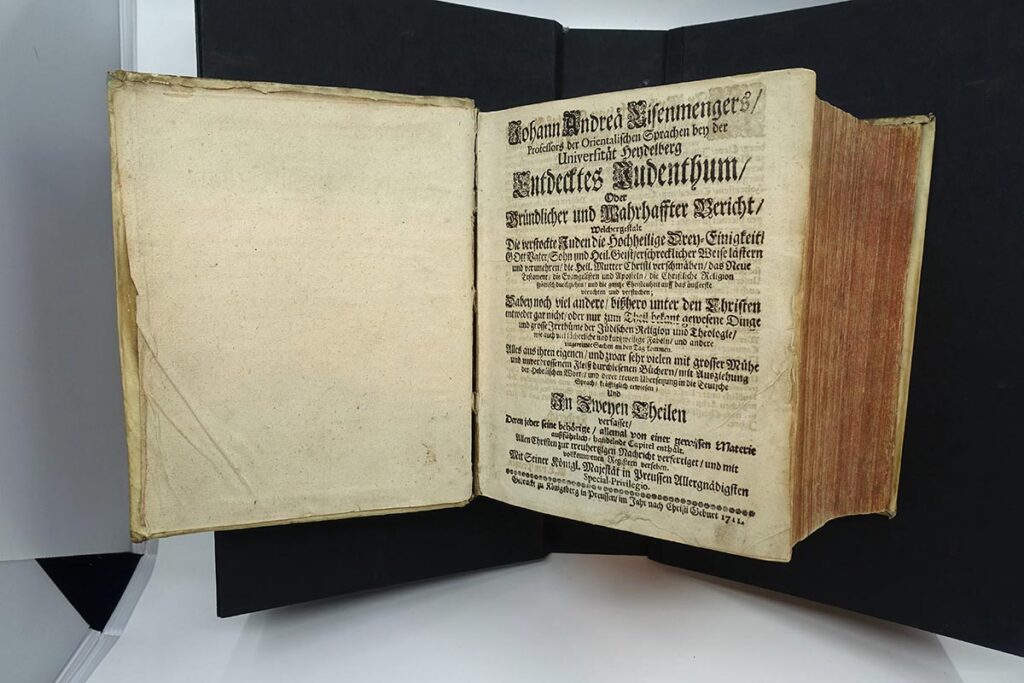

Schwab: Yes. He was running long-con for 19 years, and married a woman, and fathered children. Like, there is something almost admirable, if it wasn’t so horrifying and scary, about this incredible major portion of his life that he devoted to this deception. But yeah, it was a long-con so that he could then assemble basically every single thing that he could find in the Talmud that he deemed objectionable, offensive, upsetting.

Not just anti-Christian blasphemy, but any time there was an indication that non-Jews were treated differently than Jews, especially if it was inferior. So he puts together this massive volume with several thousand of these anecdotes of things that are all very much in the Talmud. And this is a big deal, because a lot of other times when people say, “oh it says in the Talmud this.” They might be making stuff up. He’s quoting, and says “it’s on this actual page.” He’s taking it totally out of context, he’s pretty loose with his translations, but the key is he never is making up any of these texts. So he is incredibly meticulous about his sourcing.

Yael: Chapter and verse, can cite it.

Schwab: Exactly. Chapter and verse. The Talmud is not really organized into chapters or verses.

Yael: Fair, fair. That it’s definitely not.

Schwab: You know, but what page it’s on.

Yael: You’re lucky if you get a colon separating two stories.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: I have two questions. One is, why?

Schwab: Why? ‘Cause he hates Jews, yeah.

Yael: And the other is, how did he get to this point? Like, why does he hate Jews? Not that anyone needs a reason.

Schwab: Yeah. It’s the question that kept me up at night as I was researching this and trying to figure it out. And no one really has a good answer of like, how could this person’s hatred be so virulent, that he spent decades of his life on this project? What would drive a person to that?

Yael: Right. It’s not even the why for me, it’s the, okay so you hate Jews, so then you punish yourself by spending two decades amongst them?

Schwab: Mm-hmm, right.

Yael: So what’s the big reveal, and what happens?

Schwab: He attempts to get this published. He prints 2,500 copies of his book in 1699. This is in Austria.

Yael: Does he divorce his wife?

Schwab: He doesn’t divorce his wife. There’s not a lot about his family, but I’m so curious what the story is there. Because at some point she must know what’s going on with him. As far as we know, they don’t divorce. She stays with him. His kids… Their mother is certainly Jewish, their father converted under false pretenses. But as all of this starts to emerge, they don’t identify as Jews. They very much align with him, and aren’t like, “wow, we also were deceived by our father.” They’re, you know, in his league, sort of.

Yael: So he publishes this book.

Schwab: Yeah, he prints it, and is attempting to distribute it. The Jews appeal to the Emperor and say, “If this book comes out, it’s going to be horrible. This is an incredibly anti-Semitic text, please help us in stopping this book from being distributed.” And the Emperor does help them. He’s sympathetic to Jews, and he doesn’t want to see this book get out. There’s maybe some sort of negotiation between the Jews and Eisenmenger about this, because he says, hey, this isn’t just a question of whether this book should or shouldn’t be published. I’ve invested not just my life, but apparently all of his life savings, all of his money he put into publishing this work. And he said, “I’m going to be, you know, out all that money if I’m not able to sell the book, I’ve put all of this money into it.” It seems like they’re negotiating over this, and they maybe agreed in principle, but a question of like, certain negotiating over price of-

Yael: Like, Will they cover his expenses-

Schwab: Right.

Yael: So that he doesn’t release it?

Schwab: So the Jews offer 12,000 florins, I think it’s something like $100,000 in 2023 American currency, to not publish the book. And he says, “I need 30,000 florin.” They are not able to come up with that sum, and while this sort of negotiation is going back and forth, he dies of apoplexy. He probably had a stroke of some sort. It doesn’t seem like it’s necessarily related to any of this, you know? Like, it’s 1704, people die all the time. And he’s in his 50s.

Yael: It’s not as though there’s a theory that he was once a genuine Jew and then he got a brain tumor and changed his tune, and then dropped dead.

Schwab: Oh, interesting. I thought you were asking if they secretly assassinated him or something. No, I don’t think that they’re related. I think he just, you know-

Yael: I was just speculating.

Schwab: Yeah, I think he just died as people sometimes-

Yael: Do.

Schwab: I was about to say, “tragically do.” I- I don’t know that I feel that bad, um, about this guy dying. But, his children continue his efforts. And they say, “hey like, we wanna still sue the Jewish community for the damages that were caused, and especially now that he died and has left us no money.” Uh, and his children managed to get the book published eventually, in a neighboring kingdom, in Prussia. I’m pretty sure I have those two right, and it’s not reversed. But they get it published eventually, in Konigsberg in Prussia, where the Prussian king was more amenable to Eisenmenger’s views, or I guess a different way of looking at it is less amenable to Jews and their way of looking at things. So the book gets published and gets widely distributed and read, and sort of really becomes the stepping off point for a lot of anti-Semitism. And there are things, if you go on the Internet today-

Yael: (laughs).

Schwab: There’s all sorts of hateful stuff being written about Jews, and when people say, “oh it says in the Talmud, you know, this, and that’s what Jews believe.” A lot of that still comes back to Eisenmenger’s work, and some of the things that he published and pointed out, um, that were said.

Yael: Seems like It’s a predecessor to the protocols of the Elders of Zion-

Schwab: Except that that’s made up. The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, right? And this is, it’s not made up. Again, wildly out of context, translated poorly, but they’re real and he sources them exactly. And he was incredibly meticulous. Obviously he was very, very talented that he was able to do this. But in my opinion, a real waste of his talent, to be using them in this way.

Yael: Do we know what his end game was? Like, did he want to incite violence? Or it was enough to him that these ideas were percolating? And that anti-Semitism would live on.

Schwab: Yeah. I don’t know if he really wanted violence, specifically, but I know he definitely wanted to, wake the world up to the dangers of the Jews sort of thing. And he did. Like, he blew this thing wide open. Up until this point, there was very little understanding, you know, of the Talmud. Nothing like this had ever existed before, so for the anti-Semites, he gave them like, the best text they could hope for.

Yael: So I have absolutely no desire to stoke further anti-Semitism.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Oh, great.

Yael: I think that there are texts outside of the Talmud, particularly liturgical texts that I’ve heard other people talk about as potentially divisive or dangerous because of the way that they speak about non-Jews.

We’re recording this right before Passover though I know it won’t be released until well past Passover, but there is a portion of the seder that, in the aftermath of the discussion of the Exodus, and the discussion of the Exodus, there is some language that speaks to God pouring out his wrath on the nations of the world, and It’s something that’s part of our tradition and our liturgy, and it’s part of a poetic liturgical book, but I understand why there are some things like that, that cause concern.

Schwab : That’s such a great example, and I guess thinking about Eisenmenger’s work is thinking about, let’s say somebody said, “do you know that on Passover, what Jews do is get together and they sit at a table, and then what they say is that God should pour out wrath on the other nations of the world?” I’m like, “well, technically,” right? That’s not incorrect, right? That’s part of the text of the seder. You have to understand the context of like, that’s after two hours of talking about all the oppression and suffering that Jews underwent at the time of the slavery in Egypt.

Yael: It’s very similar to hearing, in any other religion-

Schwab: Yes.

Yael: You know, that God’s wrath will be invoked against the heathens. I am not in any way calling anyone who isn’t Jewish, a heathen. But what I’m saying is, it’s a religious mechanism.

Schwab: Yeah, right.

Yael: What I’m saying here is, nobody is immune. I’m not saying that the Talmud is perfect. I’m not saying that our liturgy is perfect and that there isn’t language that through a 21st-century lens, is not offensive or should be expressly seen as poetic. But, the Jews are not alone in this.

Schwab: Right.

Yael: Religion by its nature is exclusionary.

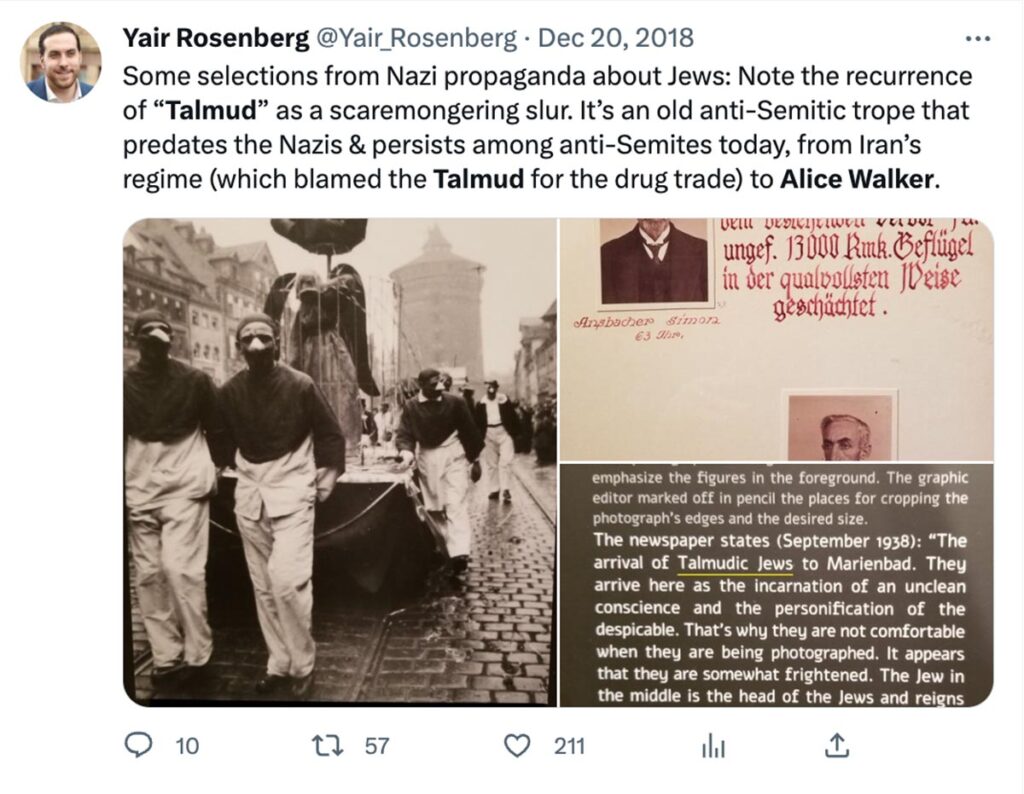

Schwab: Mm-hmm, right. This is an exercise that you could probably do, like you were saying, with any religion or with any text. The problem is this didn’t die with Eisenmenger in the early 1700s. Whenever anybody says, “the Talmud says something,” I’m just like, “the only people who ever say ‘the Talmud says'” are people who are now gonna say something like, really bad probably, you know?

Yael: Right.

Schwab: I feel like most rabbis are not like, “the Talmud says this.” Because most rabbis who are knowledgeable about it would be like, “in the Talmud, rabbi so-and-so, on this page, says this.” And there’s no author of it. Like, there’s no person who wrote the Talmud. That’s not how it works.

Yael: There is no one guy who is passing down these pieces of information. It’s really just a record of the conversations that took place among people who wanted to understand the Torah.

Schwab: Yeah. As an example of just how mainstream this approach is, one of the things that has come out in the last couple of years is, very well known, and frankly very good African American author Alice Walker, has talked about the Talmud on a number of occasions and wrote a poem. It’s entitled “It Is Our Frightful Duty to Study the Talmud.” And this is on her official website. This isn’t like-

Yael: This isn’t a ten-year-old tweet that somebody dug up. Like, she’s upfront about it.

Schwab: Right. As of when we’re recording… I don’t think we’re gonna be the ones-

Yael: No (laughs).

Schwab: That like, get this finally taken down. But this is a poem that she published I think in 2017. And I think this is genuinely what she really means. I don’t think she’s like, taking poetic license to inhabit a character and say what this character is saying.

Yael: Uh-huh.

Schwab: Like, we can assume the “I” in the poem is her. Um-

Yael: She’s not writing from the perspective of the devil, for instance.

Schwab: No, no. She is writing, I- I believe, from her perspective, And she talks about how, from her perspective, so much of what was going on in Israel today with oppression of Palestinian people, is rooted in the Talmud, and you know, She’s like, advising all of the readers, “you need to go see what it says in the Talmud so that you can appreciate how Jews feel about other people.” And there’s a point about halfway, two thirds of the way through the poem, where she says, “where to start?” And then says, “you will find some information, slanted unfortunately, by Googling. For a more in-depth study, I’d recommend starting with YouTube. Simply follow the trail of, quote, the Talmud, as its poison belatedly winds its way into our collective consciousness.”

And, like you said, in today’s day and age, if you wanted to study the Talmud, the entirety of it is available online, in English translation. Like, you don’t need to go to YouTube to like, understand what the Talmud is saying. But like, this idea that-

Yael: That it’s poison.

Schwab: It’s poison, right? And The poisonous ideas of the Talmud have like, overtaken the entire world. As somebody who has spent a lot of time studying the Talmud, I’m just like, what poison from the Talmud has wound its way into our collective consciousness?

Because the Talmud gets into like… extended conversations, you know, when witnesses need to see the new moon, does seeing a reflection of it in a pool of water count as witnessing the appearance of the new moon? That is the type of thing that we both see pages and pages and pages of discussion about, you know? Or like, what legally constitutes public property or private property? Like, that’s a- a whole volume that’s like, several dozen pages long, just on that question.

Yael: What obligations a man has to his ex wife. To his current wife. I think what’s hard for me to wrap my head around is that this is a woman whose quote unquote “art,” is fairly mainstream, and she’s incredibly well respected in certain intellectual circles that are by no means on the fringes. I have friends, people who I really, truly consider friends, who are fans of hers. And the fact that they can continue to be without engaging in this very problematic part of her belief system and her public persona, it indicates to me that anti-Semitism is so deeply entrenched in everything that even people who would never say a bad word about a Jew in their lives, are not struck by another person’s anti-Semitism because it’s so ever-present, and it’s so not a big deal. “Okay, so she hates Jews. A lot of people hate Jews.”

Schwab: What a terrible truth. The other part, I guess, that really bothers me is like, here is a person, like you’re saying… she’s obviously an artist of great talent. Like, how is it that she is… to borrow her phrase, like, poisoned by this idea? Like, how is it that a person who obviously is intelligent, like, can so easily be duped by this notion of like, what the Talmud is because she watched a couple videos on YouTube, and not ever sat down and like, thought critically, about what it is that she’s hearing, and then repeating?

Yael: This is, uh, the oldest hatred in the world. This is a hatred that goes back to the beginning of time. I’m not trying to sound like a person who sees anti-Semitism everywhere. I am not. But, when you ask, “how can this well respected public intellectual come to believe these things?” She didn’t have to learn them. They’re just there in the public sphere.

Schwab: The phrase that she employs is actually a really beautiful one, like, “the poison that has wound its way into our collective consciousness.” But the only thing I would say is like, the poison that has wound its way into the collective consciousness are the very ideas that she’s talking about.

Yael: I get a snake vibe from that, “this poison winding its way.” Like, I see the snake tempting Eve, and bringing evil to the world for the first time.

Schwab: To the whole world. Like, the notion that Jews are all deliberately working together to like, deceive the world into something. I’m just like, “wow.”

Yael: I mean, and that’s the real joke because Jews can’t deliberately work together to do anything.

Schwab: I know. If it’s anything, The Talmud is a record of the fact that Jews spend all of their time arguing with each other. About how exactly to do things (laughs).

Yael: And sometimes there’s no right answer. Sometimes we just say, “huh, we don’t know.”

Schwab: Right, yeah. Like, often it’s not even about what the conclusion is, like, for the purpose of reality or for the purpose of action. It’s just like, “Let’s argue so we could all understand each other’s positions.”

Yael: Yeah, I think that Eisenmenger is one of many people in history who takes an opportunity to turn certain elements of our religion against us, and I am sure that that is the case for every religion. Unfortunately, this mechanism of criticizing Jews persists until today, we are still very much subject of the public’s perception of Jews.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. But the message I would say, I guess, we are living in an incredible age of availability of information. So if you’re gonna study something, you know, there is an opportunity to really study and really engage with a lot of these things.

Yael: And I think the bottom line is that regardless of what you may find in the text, or what position in a debate you might find expressed, the pages of the Talmud are not Judaism itself. It is a foundational text, but we don’t pick up words off the page and judge them out of context. They are part of a much more fulsome tapestry of a variety of texts and traditions and groups of people, woven together over several centuries.

Schwab: It’s a record of the process.

Yael : It’s a court transcript, honestly. It is a stenographer, writing down-

Schwab: Though, also a lot of funny stories in there. Like, there are also like, stories, jokes. There’s other stuff in there too, but yes, a lot of it is… yeah, would look a lot like a court transcript, or a transcript of like, Supreme Court Justices debating.

Yael: Correct. It’s oral argument at the Supreme Court, is what it is.

Schwab: That’s what it was. I personally, like, this story for me, there are times in my life where I’ve spent a lot more time studying the Talmud, and times in my life where I’ve spent less. It’s kind of a weird thing to say, but I actually feel spending time learning about Johannes Eisenmenger has sort of inspired me to say, “I should be spending more of my time studying the Talmud proudly.”

Yael I’m gonna check back with you in a week and see if you still feel that way. I wish you the best of luck-

Schwab: (laughs) Thank you.

Yael: And I am not even gonna go as far as to say that I’m gonna try it. Because I’ve tried it and I’ve failed it, and I know my own limit.