I love imagining impossible and outlandish scenarios. Like, ‘this would never happen’ kind of moments. Like, imagine Donald Trump and Barack Obama kicking it on a couples retreat with their wives. Or like, Kim Jong-Un, the Supreme Leader of North Korea, giving it all up to form a boy band. Not gonna lie, I’d watch that reality show in a heartbeat.

But sometimes, outlandish scenarios do come true. Say… in Israel, 1977. Back then, Israelis would have sooner imagined dinosaurs walking the streets of Jerusalem than envisioned the Egyptian president addressing the Knesset. But that’s exactly what happened. The leader of Israel’s old enemy, Egypt, came for a visit.

And what happened next changed history.

Jerusalem is a majestic city that’s played host to quite a few dignitaries over the centuries. Alexander the Great. Saladin. Kim Kardashian. And yet, I’d argue that among Jerusalem’s most important visitors was a man that Israeli diplomat and advisor to five Prime Ministers Yehuda Avner describes as a quote, “long-limbed, balding, joyless-looking, deeply religious model of anti-charisma… hiding spinelessness under his extravagant uniforms.”

But looks can be deceiving. Yes, the man who stepped off the plane on November 19, 1977 was indeed long-limbed, bald, and deeply religious. But behind that hid a sharp sense of humor and a backbone of steel. Four years before, he had used that backbone to confront Israel on the battlefield, launching a surprise attack on Israel’s holiest day. And that day, he harnessed that will to do the unthinkable. Because Anwar Sadat, President of Egypt, was the first Arab head of state to visit Israel in the name of peace. And the story of the two days he spent there is absolutely wild.

I wasn’t born yet, but my dad had a front-row seat to the action. At the time, he was studying in a Jerusalem yeshiva. And he confirmed that it really was as wild as it sounded. How the hesder boys – who split their time serving in the Israeli army and studying in yeshiva – broke out into spontaneous dance, celebrating the fact that they wouldn’t ever have to go back to war.

He told me about the hundreds or thousands of people massing on the street near the King David Hotel (which by the way has the absolute best chopped liver) to wave to Sadat as his motorcade approached.

But best of all was my dad’s incredible story of trying frantically to find a TV so he could watch Sadat’s drive into Jerusalem. He ended up in a friend’s relatives’ house (so Israel) in the Haredi neighborhood of Geulah. Shout out to Uri’s pizza (best dipping sauce in the game).

Now, haredi, or ultra-Orthodox folks, generally don’t have TVs. So my dad watched in amazement and hilarity as these guys closed the window shutters (also known as trissim) and rolled out a dinky TV, which they all clustered around to watch history in the making.

I mean, this moment had it all, all the drama, all the suspense, it almost felt too real to be true. But, WHY? Why was this moment so historic, that it caused a haredi family to whip out their TV?

The story of Egypt and Israel is literally 3,000 years old. The Hebrew name for Egypt, Mitzrayim, means “straits.” As in, dire straits. As in, straitjacket. As in, the narrow place where the Jewish people were once enslaved, but from where we escaped and emerged as a nation. By the 1970s, that ancient history held an even more painful resonance. For the first few years of Israel’s existence, Egypt had been an existential threat to the Jewish people, threatening to push the entire nation – not just the baby boys, like Pharaoh – into the sea. The Jewish state had faced off against its mighty southern neighbor twice within the first decade of its life. But a month after Israel’s ninth birthday, the Jewish state managed to turn the tables. Big time.

Because during the Six Day War of 1967, Israel took out the entire Egyptian air force in the span of three hours. Captured the Golan Heights from Syria, the West Bank from Jordan, the Sinai and Gaza from Egypt. Utterly humiliated the Arab armies who had dared to boast that the days of the Jewish state were numbered. And assured itself, and its neighbors, that the existential threats from the Arab world were a thing of the past.

For a few years, Israelis rode that wave of euphoria. Many thought that the Arab world wouldn’t dare attack again. That in the world’s toughest neighborhood, peace and security could only be bought by might. There was even a word for this in Israel. It was called “the conceptzia.” This was the brash Israeli confidence that all would be good. They were invincible.

But Egypt had other plans.

Anwar Sadat rose to power in 1970, after his predecessor, Gamal Abdel Nasser, died of a heart attack. From the start, Sadat made his intentions towards Israel clear. In an interview with the New York Times in December of 1970, he explained, quote:

“I am just asking for the liberation of my land, which is my right… Israel has started on the 5th of June [1967] aggression of three Arab states and has occupied lands from these three Arab states. All we asked is that Israel retreats, and then there is the Security Council resolution in which it is stated the stages of the solution of the whole problem; even the refugees problem is stated in this resolution.”

Now, we can nitpick Sadat’s interpretation of history. But his vision of the future was pretty clear. He had no intention of letting Israel get away with embarrassing Egypt.

And Sadat chose October 6, 1973 to get even. We’re heading into the fiftieth anniversary of Israel’s most painful war, and we’ve got some powerful episodes coming up in the next season to unpack the war in detail, so stay tuned for that. But for the purposes of this episode, here’s what you need to know about that horrible October.

For weeks, there had been signs that Egypt and Syria were planning something big. Although it had made feints of this sort previously, Egypt was massing troops and equipment, readying itself to cross the Suez Canal. King Hussein of Jordan even flew to Tel Aviv to warn Prime Minister Golda Meir that war was coming – from two fronts. (Nerd corner: King Hussein didn’t come to Israel out of the goodness of his heart: he just had enough problems without the war potentially spilling over into his territory.) But the signals were ignored. The Israeli government was confident. The surrounding Arab countries wouldn’t dare, Israel thought. Not after 1967.

But they did dare. On Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the Jewish calendar, Egypt and Syria launched a simultaneous, coordinated attack from the north and south. Caught unawares, the Israeli army scrambled to respond. And for the first week, things looked grim. The Egyptians cut through the infamous Bar Lev fortifications as though they were butter. In the Golan, 1400 Syrian tanks, equipped with Soviet-made anti-tank missiles, stared down an Israeli tank force half that size. Victory hinged on a few decisive battles. But the tides began to turn a week into the war, and by October 24 and 25th – nearly three weeks into the war – came the Battle of Suez, which ended with the Egyptian Third Army completely encircled by an Israeli force.

Now, historians have argued about who “won.” Predictably, both Israel and Egypt claimed victory. And while I’m inclined to see Israel as more of the victor for a number of reasons – including both the encirclement of the Egyptian Third Army and the fact that the war ended with Israeli tanks pointing towards Damascus and Cairo – I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that it was a Pyrrhic victory. Because it cost more than 2,500 Israeli lives. Carved a deep wound into the Israeli psyche that the country is only now beginning to air out. And punctured the myth that Israeli security could be achieved by military might alone.

Israelis may have mourned the loss of their seeming invincibility. But that loss was all Anwar Sadat needed in order to come to Jerusalem 4 years later.

You see, the Arab world had never forgiven Israel for winning the Six Day War. After Egypt’s humiliating defeat, Sadat needed to prove that the Israelis could be brought down. Not to mention, how could Egypt possibly allow this Jewish upstart nation to keep the Sinai Peninsula, a landmass that’s like also three times the size of Israel itself, that had once belonged to Egypt?

I highly doubt that Sadat believed that he’d be able to wrest back the entire Sinai by force. But I do know that he wanted leverage. And that’s exactly what he got. In the words of Palestinian intellectual Sari Nusseibeh, “The Arabs had shown that the Israelis were mortals after all. We won by not losing.” Sadat’s wife, Jehan, agreed, telling an Israeli newspaper that her husband “needed one more war in order to win and enter into negotiations from a position of equality.”

Keep that in mind as you’re listening to this story. Because it’s a strange and miraculous tale, peppered with moments of unexpected levity. Animated by the unlikely but deep and mutual respect between the leaders of two enemy countries.

And yet, all this hope and levity and respect bore an unimaginably high price tag: thousands dead. Thousands more wounded. A bitter, costly war that perhaps could have been avoided. Or that Israel could have prepared for, had it only listened to the warnings. Egypt and Israel had talked about peace before. But neither side was open to the serious and painful compromises that peace would require. Not until after the Yom Kippur War.

Because before then, Sadat’s demands had been a non-starter for Golda Meir. In a 1970 interview with the New York Times, he demanded that lsrael give up “every inch” of territory gained in the Six Day War – a concession Meir dismissed out of hand. And understandably! Control of the Golan and the Sinai Peninsula made Israel a lot easier to defend. Israel’s Arab neighbors had been attacking for decades. Why should the tiny Jewish state give up territory it had won fair and square? Plus, Sadat wasn’t even promising peace; returning to ’67 borders was Egypt’s precondition to merely recognize Israel as a state!

Still, for two years, Sadat and Meir talked around each other. Through intermediaries, through the press, both made it very clear that the other was being unreasonable. In a 1972 interview with the famous Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci, Golda Meir said dismissively of her Egyptian counterpart, “He’s not a bit ready to sit down at a table with me… He refuses to negotiate with us directly… It’s senseless, useless!” So no agreement materialized. And then, it was October of 1973, more than 2,500 Israelis and 15,000 Egyptians were dead, and Israel was left shaken and scarred and traumatized.

It was precisely this trauma that brought them to the negotiation table. Both countries – not to mention global superpowers like the US – were eager to officially end the war. Because a war doesn’t end when both sides stop shooting. It ends when both sides sit down and agree on what the end of hostilities actually looks like. For Egypt and Israel, that agreement came in 1974.

But even that is not the same as peace. It would take a few years for Egypt and Israel to actually be able to hammer out what peace would look like. And that peace agreement would come from a most unlikely figure: the face of the Israeli right wing.

Four years after the Yom Kippur War and three years after the disengagement agreement that officially ended it, Israeli society went through a kind of revolution. For the first time in Israel’s history, the Labor Party lost an election. Israel’s right wing was officially in power. The new Prime Minister spoke Hebrew with an Eastern European accent. Wore thick 70s-style glasses and impeccable suits. Looked like a kindly, harmless grandpa. But appearances are deceiving. Because behind the accent, spectacles, and well-cut suits, was a force that shaped the course of Israeli history. Wanna guess who I’m talking about?

That’s right: my main man, hero of this podcast, someone I sometimes disagree with, but always admire, the sixth Prime MInister of Israel, Menachem Begin.

I know, it’s practically a cliche how much I stan Begin. But come on! The man played a major role in averting civil war (shoutout to our Altalena episode).

He sent Israeli boys to take down Iraq’s nuclear reactor (shoutout to our Osirak episode). His every move was calculated to prevent another Holocaust (shoutout to our German reparations episode). His youth had been spent fighting the enemies of the Jewish people (shoutout to our Black Saturday episode). But most amazing of all, he was the man who made peace with Israel’s implacable enemy. The right-wing Menachem Begin is the man behind the concept of “land for peace.”

There’s a certain resonance to the fact that Menachem Begin, that famous “hawk,” that devotee of Jabotinsky, that so-called terrorist who had escaped the $50,000 bounty the British placed on his head, the man who many American Zionists did not want on the shores of the U.S. – that man was the first Israeli Prime Minister to broker peace with an Arab nation.

And in a way, I think it makes sense for a so-called hawk to be the one to broker peace. Because a peace treaty that comes from the left could be shouted down by the right. Just look at what happened with Prime Minister Rabin – a dovish leader who tried to forge peace despite the fiery objections of his country’s right wing. (One more time – see our episode about Rabin’s assassination.) But concessions from the right? How could the left not follow?

Not that the country’s right wing followed Begin unquestioningly. But we’ll get there.

So back to November of 1977. The four-year anniversary of the Yom Kippur War has come and gone. Seven years into his tenure as head of state, President Sadat addresses the Egyptian Parliament. And among the bluster, the promises that “there is no power on earth that can stop me from demanding total Israeli withdrawal from occupied Arab lands and the recovery of the Palestinians’ rights,” Sadat went off-book. He says something extemporaneous, from the heart. Quote, “I am ready to go to the end of the world if this would prevent the wounding, let alone the killing, of a soldier or an officer of my boys…. Israel will be surprised when it hears me say that I won’t refuse to go to their own home, to the Knesset itself, to discuss [peace]”.

And in Jerusalem, Menachem Begin was listening. And when a reporter asked what he thought of Sadat’s offer, Begin responded: “If President Sadat really means it, then Ahlan wa-Sahlan.” Arabic for “Welcome.” Two days later, Begin addressed the Egyptians via radio broadcast. “In ancient times, Egypt and Eretz Yisrael were allies, against a common enemy from the north. Indeed, many changes have taken place since those days. But perhaps the intrinsic basis for friendship and mutual help remains unaltered. We, the Israelis, stretch out our hand to you… No more wars – peace – a real peace and forever.”

Less than a week later, Sadat was on a plane to Israel.

President Sadat was scheduled to arrive at 8pm on Saturday, November 19th. Begin later explained why he’d chosen 8pm: I wanted the whole world to know that ours is a Jewish state which honors the Sabbath day. We respect the Muslim day of rest: Friday. We respect the Christian day of rest: Sunday. We ask all nations to respect our day of rest: Shabbat. They will do so only if we respect it ourselves.

A few hours after the end of Shabbat, a who’s who of Israeli dignitaries gathered at Israel’s sole international airport. Prime Minister Begin, of course. President Ephraim Katzir. Former Prime Minister Golda Meir. IDF Chief of Staff Motte Gur. The legendary and wildly controversial commander Ariel Sharon. Not to mention an IDF honor guard, a military band, and some two thousand journalists who had flown to Israel to capture this historic moment.

The plane touched down, but no one emerged. Chief of Staff Motte Gur had been suspicious from the start. Was he right? Was this a trap? But everyone waited. And finally, the door opened, letting loose a crush of journalists, who began setting up their positions to capture that first historic handshake between their President and an enemy Prime Minister.

Still, Sadat did not emerge.

He may have been ascetic and joyless-looking, as Yehuda Avner described him, but the man knew how to make a dramatic entrance. As Israelis around the country held their breath, as my father watched on a bootleg TV, amid the click and whir of thousands of cameras, finally, the president of Egypt stepped off his plane. Here he was at last: an enemy made flesh.

This is the thing about enemies. You know them. You watch them. You listen to their speeches and collect intelligence and study their habits. The Egyptians and the Israelis had never officially met. Yet they knew each other, down to the last detail. And Sadat was not afraid to crack a few jokes at the Israelis’ expense.

“Here you are,” he said to Ariel Sharon. “I tried to chase you in the desert. If you try to cross my canal again, I’ll have to lock you up.” And Sharon, laughing, shook Sadat’s hand and said, “No need. I’m the minister of agriculture now.” LOL.

Accounts are split on what he said to Israeli military leader Moshe Dayan. Avner reports he merely joked, “Don’t worry, Moshe. It’ll be all right.” But another witness claims that he said, “You must let me know in advance when you are coming to Cairo, so that I can lock up my museums.” You see, Dayan was notorious for pilfering ancient artifacts from archaeological excavations. Personally, I think this one is way funnier, so I kinda want this to be real. Let’s go with it.

To the Chief of Staff Motte Gur, he teased, “You see, it is no trick. I wasn’t bluffing,” a statement that was met with a formal salute.

But to Golda Meir, he said, without a trace of laughter, “I have wanted to talk with you for a long time.” And she, looking steadily at the man who had attacked her country and whose war arguably cost her the Prime Ministership, replied, “And I have been waiting for you a long time.” Sadat responded, “But now I am here,” and Golda simply said, “Shalom. Welcome.”

I don’t know if you know this about me, but I’ve never actually led a country before into war. Still, it seems to me from this exchange that there’s a fine, almost invisible line between the intimacy of enemies and the intimacy of friends. Both relationships are based on deep and mutual emotion, and a kind of knowing recognition: I know this person down to their bones.

And now, Sadat would get to know the real Israel, the country that had for so long been his enemy. He visited the Temple Mount and prayed at Islam’s third-holiest site, the Al-Aqsa Mosque. He paid his respects to the Christian community at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. But it was perhaps his visit to the Israeli Holocaust Museum, Yad Vashem, that was most symbolic.

He looked at the pictures. He stood in silence before the crypt where ashes from the crematoria had been reburied. He inscribed the guest book with the following prayer: “May God Guide our steps toward peace. Let us end all suffering for mankind.” And he told the museum’s chairman that he would, quote: “not forget this exhibit.”

Now, I want to make something really clear. Maybe you’ve grown up learning about the Holocaust in school. Maybe you have relatives who survived, or who didn’t. And maybe you’ve been to a museum that commemorates the scale of the genocide. So a visit to the Holocaust museum might sound mundane to you. But coming from Sadat, head of an enemy state? The man who had attacked on Yom Kippur?

I don’t think I can exaggerate how much his visit to Yad Vashem meant to the Israelis. The trauma of the Holocaust was very much alive in 1977. It was important for Sadat to understand that, in a real and visceral way. Not just because the first step to peace is recognizing and validating the other person’s hurt – see our Kfar Qassem episode from earlier this season for more about forgiveness and acknowledging pain. If you are sincere about reconciling with your enemy, the first step is telling them, I see your trauma and understand why it impacts and motivates you.

But there was another reason that Sadat’s visit to Yad Vashem was so important. And that was his former admiration for Adolf Hitler.

Oh yeah. You didn’t see that twist coming? Well, I have to go back a few decades to explain this one, because I think it’s critical, to really get how monumental this Yad Vashem visit was. See, as you know from our Black Saturday and San Remo episodes, the English had set up shop in the Middle East after WWI. And the locals weren’t necessarily thrilled. So as the chaos of WWII spilled over into the Middle East, Sadat saw his chance. He conspired to overthrow the British with help from – you guessed it! – the Nazis. His stint in prison did nothing to quell his pro-Nazi sympathies, even after the end of the war.

In fact, in 1953 – less than a decade after the Holocaust – an Egyptian newspaper asked some famous Egyptians to write a hypothetical letter to Hitler, if he were still alive. (And yes: that is a bonkers thing for a newspaper to do.) Sadat, who was at the time merely a rising officer in the Egyptian Army, reportedly responded with a gushing letter:

“Dear Hitler: I salute you from the depths of my heart. Though you have apparently lost your war, you are the real winner, for you succeeded in breaking the lines between Churchill and his accomplices. True, you have made a few mistakes by fighting on too many fronts, but you have become an eternal leader of Germany and no one ought to be surprised if you will rise to power again or if the world will see another great Hitler.”

I mean. Yikes. And yet, here he was, at Yad Vashem, up close and personal with Hitler’s legacy and being honest about it. It’s unbelievable.

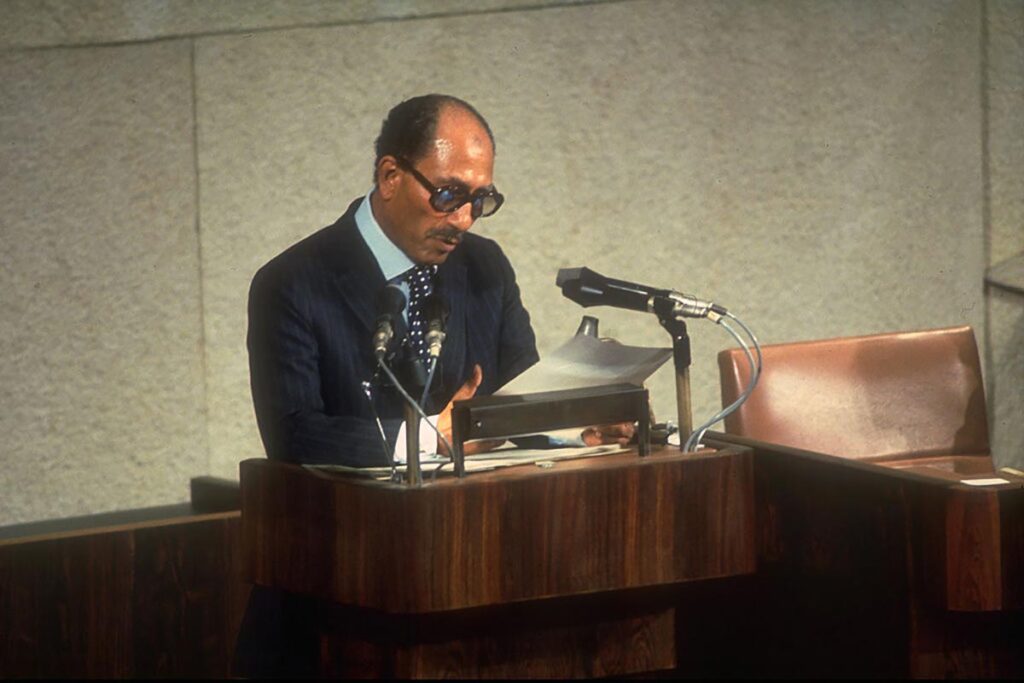

This new empathy became clear when Sadat addressed the Knesset later that day, in a speech studded with Biblical references: “If I said that I wanted to avert from all the Arab people the horrors of shocking and destructive wars, I must sincerely declare before you that I have the same feelings and bear the same responsibility towards all and every man on earth, and certainly toward the Israeli people. Any life that is lost in war is a human life, be it that of an Arab or an Israeli.”

Still, Sadat’s vision was uncompromising. In Arabic, he informed the Knesset that the Arab nation had a quote, “legitimate right to liberate the occupied territories.” Which, for the Israeli government, was kind of a nonstarter. There was simply no way they were going back pre-67 borders.

And yet, Begin’s answer to Sadat was decisive and surprising. Because he wasn’t talking to Sadat alone. He addressed President Hafez al-Assad of Syria. King Hussein of Jordan. Even, quote, the “genuine spokesmen of the Palestinian Arabs.” (Which, I’m guessing, was his way of saying “not the PLO.”) To anyone who was listening, Begin said:

“President Sadat knows, as he knew from us before he came to Jerusalem, that our position concerning permanent borders between us and our neighbors differs from his. However, I call upon the President of Egypt and upon all our neighbors: do not rule out negotiations on any subject whatsoever.”

In short, he was saying, guys. Let’s talk.

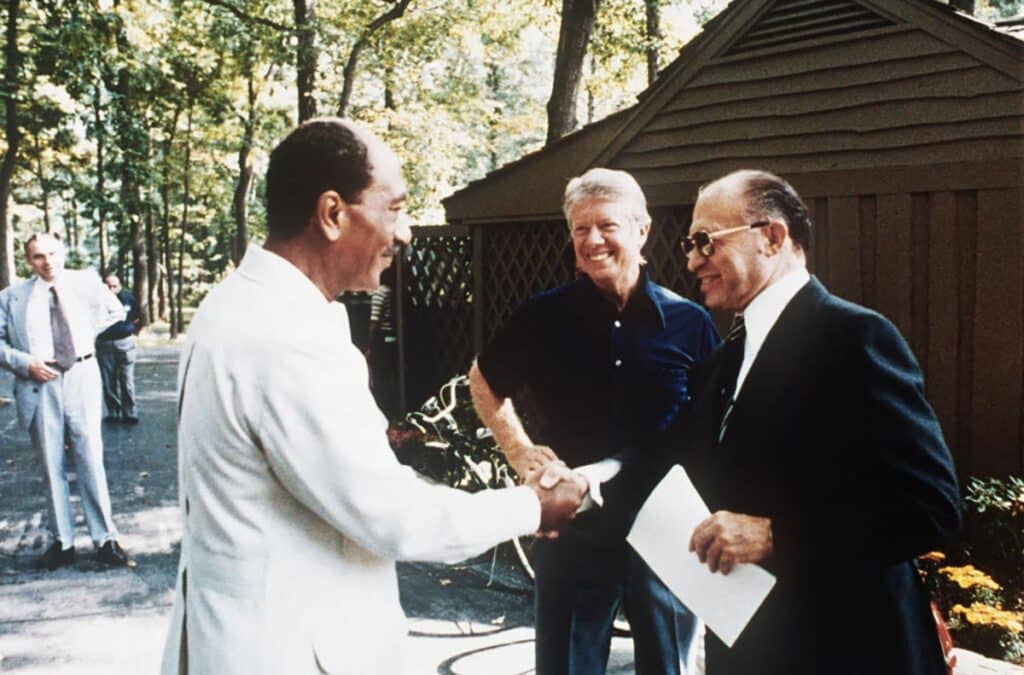

The other parties didn’t answer Begin’s call. But Egypt sure did. For over a year, the two countries negotiated. Hard. So hard, in fact, that direct talks broke down by January 1978. Things were looking grim when American president Jimmy Carter asked Begin and Sadat to meet him at Camp David in September. It was there that the three nations hammered out the documents that would become a final peace treaty between Israel and Egypt. And, on March 26th, 1979, Begin and Sadat signed the first ever peace treaty between Israel and an Arab state.

For Israel, this was very nearly an unqualified victory. They got recognition from an old enemy. They got a guaranteed end to the hostilities that had existed since 1948. They got free passage through the Suez Canal and access to the Strait of Tiran and the Gulf of Aqaba.

But. They had to give up the Sinai. Which was, for many Israelis, highly problematic. Because the Sinai wasn’t just a landmass three times Israel’s size, which made the Jewish state that much easier to defend. It was also home to a number of Israeli communities. Because the Israeli government had started building up the Sinai in 1975. In fact, Israelis had moved there with the full encouragement and support of the government.

And now, they refused to be uprooted. For the first time – though not the last – the IDF was asked to evacuate Jews from their homes. And many in Israel’s right wing were, to put it mildly, displeased. In the Knesset, MK Geula Cohen – one of Begin’s former protegees – demanded that the prime minister resign, telling a Washington Post reporter in October of 1978 that with this deal, “Begin has sent us to the gallows.” But Begin, though hurt by Cohen’s dismissal, forged on with the proposed treaty, which was signed in 1979, earning him and Sadat a Nobel Peace Prize. The settlements in the Sinai were evacuated, and in some cases completely destroyed, by 1982.

But by then, the landscape of the Middle East had changed. Israel was embroiled in another war, with another neighbor. And Sadat – the first Arab head of state to make peace with his Jewish neighbor – was dead.

In the Arab world and in Egypt in particular, Anwar Sadat’s legacy is complicated. Sure, he proved Israel wasn’t invincible. He brokered the return of the Sinai. He opened up Egypt’s economy and cut back the power of Nasser’s secret police. But he also made peace with the enemy, alienated the Arab League. In the wake of Egypt’s peace treaty with Israel, 17 Arab nations and the PLO hit Egypt with political and economic sanctions, even expelling the country from the Arab League, and moving Arab League headquarters from Cairo to Tunis.

Within Egypt, Sadat grew increasingly unpopular among the right and the left wing alike. And the more unpopular he grew, the more he cracked down, rounding up activists and tightening control of the media. But it was a Jihadi Islamist group that took matters into their own hands. And they chose a most ironic location to do so.

Each year since 1973, the Egyptians held an annual victory parade to celebrate their breach of the Bar-Lev line – the fortifications that Israel had built in the Sinai to prevent just such attacks. But on October 6, 1973, 80,000 Egyptians soldiers breached the line, holding their territory for two bloody days before the Israelis beat them back. Despite the fact that the breach didn’t actually result in an Egyptian victory, it was enough to restore some Egyptian pride. And while the Israeli perspective might be to laugh at the Egyptians’ low bar for victory, remember this: they did what they set out to do. The Yom Kippur War proved Israel wasn’t invincible. And that is why Egypt held a parade.

But the 1981 parade would be different from all others. An inconspicuous bearded man made his way towards Sadat, who stood on stage, watching his troops go by. Thinking the man was a soldier, Sadat saluted him. But the salute was met with three grenades, only one of which went off, and a chorus of backup gunfire. And though the first bullet had hit Sadat’s neck, the assassin nonetheless emptied his entire clip into Sadat’s prone body, as if for good measure. Exultant, he cried, “I have killed the Pharaoh!”

But the legacy of the so-called Pharaoh lived on. And where the Biblical Pharaoh had once been an enemy of the Jews, this Pharaoh, at least, would have a much more complicated legacy, a friend of the Jewish people.

So that’s the story of Sadat’s visit to Jerusalem, and here are your five fast facts.

- The road to peace between Israel and Egypt was rocky. The two countries fought four wars between 1948 and 1973. But for Egypt, the 1973 Yom Kippur War had proven that Israel was not invincible, and it was on these terms that Sadat was able to make peace.

- eleven days after announcing his willingness to go to Israel, Sadat was on a plane to Jerusalem, where he was met with great fanfare. Sadat greeted his Israeli counterparts. He gently poked at some, but his relationship with current PM Menachem Begin and ex-PM Golda Meir was one of mutual respect, even a sort of bonding.

- During his time in Israel, Sadat visited the religious sites of all three Abrahamic religions. He also toured Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust museum. But his speech at the Knesset was the highlight of the trip, in which he counseled Israel to give up the concepzia that might was the only way to security. Two years later, after much arduous negotiation, the two countries signed the first peace treaty between an Arab country and the Jewish state.

- Many Palestinians felt betrayed by the treaty. Because while Sadat entered negotiations on condition that they would serve as the foundation for advancing Palestinian statehood, that’s not what happened. In reality, the new peace treaty cut the Palestinians out of the equation, and the Palestinians and the rest of the Arab world saw their leverage slip further out of their grasp.

- Though many Israelis celebrated the prospect of peace, some were deeply skeptical – including the Israelis who had settled in the Sinai with the express encouragement of the government! But the Israeli opposition was nothing compared to the sentiment on the Egyptian street. Four years after his visit to Jerusalem, Sadat was assassinated – a reminder that visionary leaders often pay for their reforms with their lives.

Those are the facts, but here’s one enduring lesson as I see it.

This visit, and the peace treaty, didn’t bring peace to the Middle East. The Palestinians were still stateless. The PLO still engaged in terror – which would soon drag them, and Lebanon, into a brutal and costly war. Israel gave up the Sinai Peninsula. Sadat paid for his bravery with his life.

All of this is true. But it’s not the whole story. Because to me, the lesson of the story is this: change is possible. Mortal enemies can learn to live side by side. Humans can astonish each other with their capacity for cruelty… and their capacity for forgiveness, acceptance, and reconciliation, even against the most daunting odds.

I mean, think about who Sadat and Begin were. On one side, we have a guy who’d flirted with some pretty gnarly antisemitism. I’m talking… writing Hitler a love letter! Gross. Like imagine, one of those spineless people who tweet “Hitler was right” becoming a philosemite and having a shabbat meal with you? And the animus went beyond words; Egypt and Israel had fought each other four times in less than 30 years. Meanwhile, on the other side of this peace process was an Irgun commander and so-called “terrorist” who had dedicated his life to building, and then protecting the Jewish state by all means necessary. Shaking hands with a guy who’d attacked Israel on its holiest day only a few years earlier.

Begin and Sadat seemed like the most unlikely candidates for brokering the first Arab-Israeli peace treaty. And yet, isn’t this the story of Israel, writ large? It’s a story of beating unbeatable odds. Of wrenching a future from the ashes. Of dreaming big, and dreaming bold, and writing the next chapter of Jewish history.

I’ll end with a story. In May of 1979, Begin and Sadat met on the sands of El-Arish, site of a major battle during the Yom Kippur War, to mark the official handover of the territory to the Egyptians. With them were buses full of wounded veterans, from both sides, who had been maimed fighting one another on these very sands. Some of the injuries were awful. Disfigurements. Amputations. Blindness. Paralysis. The sacrifices of a war none of them had started. Across the room, those who could see stared at each other. No one knew what to say.

For some veterans, it was too hard. They asked to be removed from the room. But others were curious. And then, a blind Israeli veteran bent and whispered to his son, Take me to them. His son, still a child, protested. I’m scared of them. How could he not be? Here were the fearsome Egyptians that had attacked on Yom Kippur, blinded his father, killed so many Israelis, and tortured their prisoners of war. Here were the Egyptians who had cheered when President Nasser declared he’d annihilate the Jewish state.

But the boy’s father corrected him gently. As he took the first step towards the Egyptian delegation, he was met by an Egyptian veteran in a wheelchair. The legless Egyptian took the blind Israeli’s hand. They shook. The room erupted into cheers and applause, as veterans who had once shot at each other embraced. Words rang out in Hebrew and Arabic. Shalom! Salam! L’Chaim! Lilhayaat! Peace. Life. So similar. So mutually intelligible.

The little boy looked at his father, bewildered. But the father hugged his boy, and said, Don’t be afraid. These Arabs are good.

I like to imagine that across the sands, in the bustling streets of Cairo and Luxor and Aswan, an Egyptian father was telling his boy the same thing. Don’t be afraid. These Jews are good. And I hope that one day, we won’t need to say “these.” These Arabs. These Jews. Real and lasting peace will bring with it our ability to say not “these Arabs,” but “the Arabs.” A word that encompasses the Palestinians, and the Lebanese, and the Jordanians, and the Saudis, and the Omanis, and the Qataris, and the Kuwaitis, and and and.

It’s already started to happen. In Egypt, in Jordan, in the Emirates, in Bahrain, in Morocco. Like Golda Meir, like Yitzchak Rabin, like Menachem Begin, like Anwar Sadat, the blind Israeli veteran had the wisdom and courage to take the first step towards his enemy. A lesson for us all.