Every Holocaust survivor’s story is a heroic miracle but there are some stories that stand out. The story of Jacob Lustman is one of those stories.

Jacob wasn’t supposed to survive the war, he was supposed to die in 1942 like hundreds of others on one random fateful day in November. A year earlier, the Nazis established a ghetto in Radom, Poland, two years into their occupation, and in 1942 they wanted to liquidate it.

The Radom ghetto was no different than the 1,000 others the Nazis constructed across Europe– it housed Jews from all over, sealed off from the rest of society in horrific conditions. The city of 81,000 at that time was home to 25,000 Jews and that quickly swelled to 33,000 once the ghetto was established.

Life in the ghetto was hard, occupants were given only 3.5 ounces of bread a day to survive on and their movement was heavily restricted. Daily, German and Polish authorities carried out random acts of violence against residents, often executing people in the street, leaving them where they fell.

Despite these conditions, heroes were forged in the Radom ghetto, including Mordechai Anielewicz, the leader of the Jewish Combat Organization. Anielewicz would go on to lead the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, the largest act of Jewish resistance during the war. He, like many others, did not survive, but they became heroes and legends for their incredible bravery and sacrifice. For now, Anielewicz was safe in Radom, receiving medical attention from Dr. Jerzy Borysowicz, who was later named posthumously a “Righteous Among the Nations” for his work treating Jews in secret.

Then the order came down, Operation Reinhard, also known as the “Final Solution,” was to go into effect.

Operation Reinhard marked the beginning of the deadliest wave of violence against the Jews during the Holocaust– all Jews in German occupied Poland were to be exterminated as soon as possible. More than two million were taken to extermination camps, camps built for one sole purpose– the mass industrialization of murder.

Jacob’s family– his mother, two brothers, wife and his two small sons all were rounded up and sent to the gas chambers. Then 6 months later on that fateful day in November, Jacob’s turn finally came.

Death in a field

Death was supposed to come to Jacob differently, he was supposed to be a direct participant in his murder. On that day Jacob was forced marched out of the city along with 1,000 other Jewish men. They were taken to a field where they were forced to dig a long trench; and then when their work was done, the SS lined 50 men up at a time along the trench’s edge, executing them with a machine gun, repeating the task some 20 times.

Somehow Jacob woke up in the grave that he had just dug. He was alive but wounded. Surrounded by bodies he managed to crawl out and escape. He was the only one who survived the executions.

Disoriented, confused, and injured he limped off into the neighboring woods and eventually passed out. He woke up to a pistol pointed at his head, there was a young woman on the other side holding it. She too was on the run from the Nazis and had to be convinced that Jacob wasn’t the enemy but a survivor like her. Finally gaining her trust she took Jacob to a secret tunnel deeper in the woods where she and 26 others were living.

The group was a hodgepodge of society, not all were Jewish, but all were enemies of the Nazi state. They managed to survive nine months underground, eating roots and grass along with the occasional animal. Eventually the Nazis discovered their hiding spot, captured the entire group, and Jacob was sent to Dachau in southern Germany.

Dachau

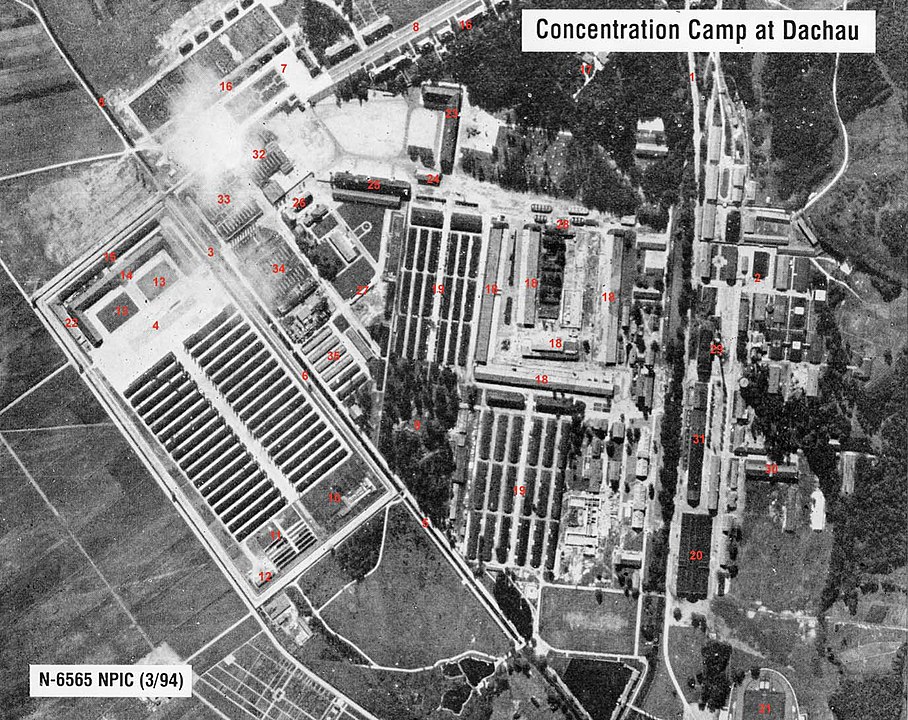

Dachau, which also had the infamous phrase “Arbeit macht frei” (Work makes one free) on its gate, was massive. It was the longest operating concentration camp, from March 1933 to April 1945 when it was liberated by the Allies, nearly all 12 years of the Nazi regime. The camp was home to more than 180,000 inmates housed in more than 100 subcamps scattered around its main complex.

Jacob was sent to Escarjisko Camp where he was forced to make ammunition for the German Army. Life in Dachau was hell and the evilness of the Nazi regime was on full display. Barbaric executions, prisoners burned alive, cannibalism, all were just some of the horrors prisoners like Jacob had to face daily.

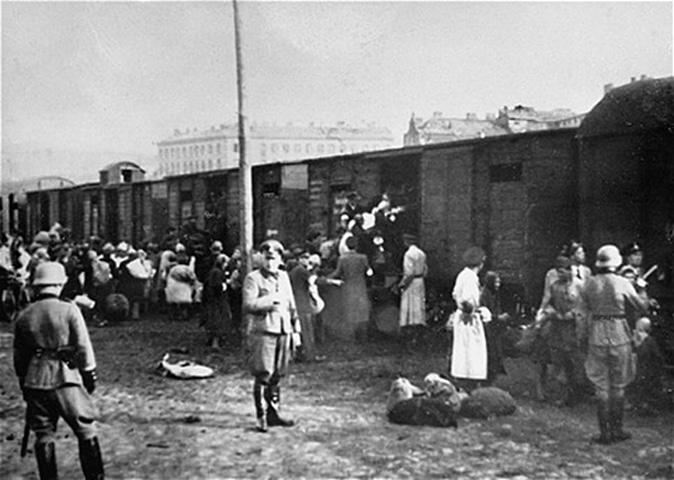

Fortunately the war was quickly coming to an end, but for the prisoners remaining at Dachau it wasn’t coming fast enough. In late April, 1945 the Nazis desperate to coverup their crimes, began their death trains, with Heinrich Himmler personally overseeing the forced evacuations. The purpose of these deportations were two-fold– to keep the slave labor apparatus running for the war effort and to remove all evidence of crimes against humanity.

A train ride south

The Nazis were meticulous in their calculations for the trains like the one Jacob was to be forced on. Most of the freight cars used were 10 meters long (approximately 32 feet and 10 inches) and the SS manual on deportations suggested that each boxcar should carry 50 prisoners. The reality of this, however, was much more grim. Most boxcars were loaded with as many as 100 people, and during the height of the deportation of the Warsaw Ghetto to Treblinka in 1942, some trains carried as many as 7,000 victims in 50 car-long trains– putting as many as 150 people into each boxcar.

Jacob was packed into a cattle car and sent south, to Austria, where he and his fellow prisoners were to be executed in the mountains, but the train never made it to its final destination. Near Vienna the train stopped, Jacob was liberated by the U.S. 3rd Army, he was finally free.

Feldafing

Now 31 years old, Jacob was put in the hands of the Red Cross. Medical records show he was sick with typhus, a disease that killed tens-of-thousands of survivors near the end of the war. A month after liberation he was transferred to Feldafing Displaced Persons Camp in Germany.

The Feldafing DP camp was the first all-Jewish camp and was home to as many as 4,000 people in 1946. Originally a summer camp for Hitler Youth, the Jewish occupants of Feldafing rebuilt their lives slowly there.

Out of the ashes a Jewish revival grew at Feldafing. One of the first things established at the camp were both secular and religious schools. A rabbinical council was started, as well as a library, several Jewish newspapers began publishing. Vocational training schools, including a nursing school, were established, a theater group was formed. Feldafing became the hub of Jewish life and culture post-Holocaust.

The residents of Feldafing became known for their zeal and passion to rebuild. General Dwight D. Eisenhower and General S. Patton personally inspected the camp in September 1945, David Ben-Gurion along with other Zionist leaders did as well.

A short time after arriving at Feldafing Jacob was introduced to Anna, who would soon become his wife.

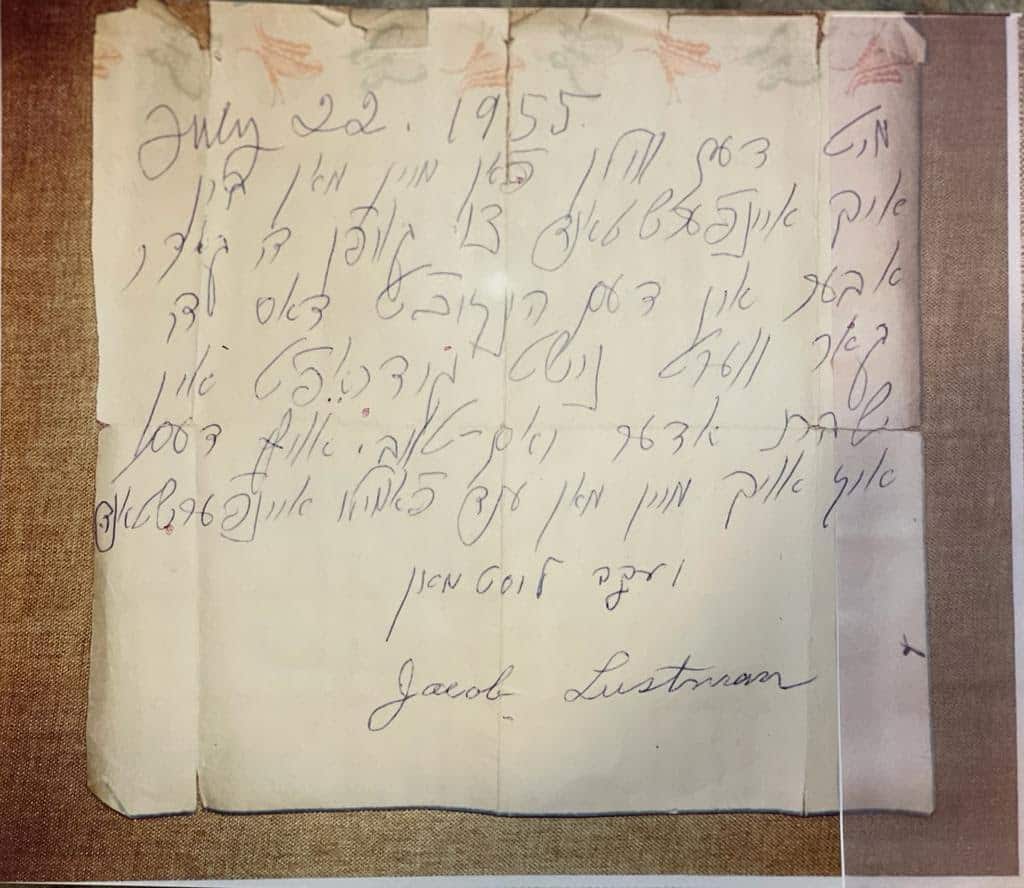

Jacob came first to America, and got a job with the Baltimore Sun, a job that required him to work on Saturdays. That didn’t sit too well with Anna, who insisted Jacob sign a contract stating that no matter what, no matter how much they needed the money, he would never work again on Shabbat.

Anna from Poland

Anna, in her words, had a “nice religious life” before the war came to her small town in Poland.

“When it came Friday, Sabbath, it was like in heaven,” she recalled in a family recording.

Anna was around 20 years old when the war broke out and it was a Friday night when the Germans invaded her family’s village.

“They started running to the houses, the Germans they came into the houses and pushed everyone out, they chased everyone out with the hands up,” she recalled.

After forcing them into the city square the Germans let the Jewish families return back to their homes. A tense normalcy developed, but then came the arm bands with the name “Jew” on them. At this time Jewish citizens were still allowed to work and Anna’s father kept working as a metalsmith, a job that caught the attention of the Germans.

“It took maybe 6 months until the Germans recognized us for good workers and they came to our shop.” Anna explained.

Her dad then started doing odd jobs for the Germans.

“We were happy, people were jealous,” she recalled.

“They wanted to give us business because they knew that they were going to keep a few families,” Anna explained. “They were going to chase out everybody, to take away, to kill or to concentration camps, and they felt that they would need a few families which they could work for them.”

Anna’s family was looked upon so favorably by the Germans that once when she got sick with typhus they arranged for a German doctor to look at her.

“We were the luckiest people in this city,” she said.

Their benevolence, however, didn’t last long.

“Then there was a ghetto and they really took out a lot of people from the city,” Anna went on to explain.

Anna and her family were forced out of their house and had to leave everything behind to go live in the ghetto. During this time Anna was still working, she had a job cleaning for an SS officer who was known for spending his nights killing people.

“Believe me, I was so scared,” she explained. She would clean his room during the day as he slept.

Life in the ghetto didn’t last long either, a few months later the Nazis started clearing it out. There were two options, either you were sent to Auschwitz or to an ammunition factory. Eventually, Anna’s family was slated to be sent to the factory to work and was waiting for the last transport out.

“I remember how we were sitting there on that truck, they had maybe 10 couples,” Anna recalled.

“There was a shoemaker, I cannot forget this, I saw this before my eyes. The shoemaker had maybe 4 or 5 kids. Little kids like 3… 4… 6… 8… whatever, so they took off those kids from that truck, and they took him off [the father]” Anna recalled. “The Germans, just taking him and putting them on the ground and then the kids start running and they took them off to kill them. The kids started running like animals, they didn’t know what’s going on … and I could see the kids run, and oy, it broke my heart.”

One of Anna’s brothers was next, the Germans told him to get off the truck. After a brief conversation he managed to convince the Germans he was fit to work and was allowed back on.

Anna was now living at the factory, sleeping like an animal in the barracks and working 12 hours a day, living off a slice of bread a day with a soup made from horse meat.

“Somehow we survived, I just don’t know how. That was just Hashem.”

Anna was sent to different labor camps across Poland and eventually to a concentration camp.

“It was so much, who could remember so much,” Anna said in the recording.

One thing remained constant, she was always working.

“We worked, we worked, we worked,” she said, her voice trailing off.

“A lot of the Jewish people lost their emunah. They said that there was no God that they couldn’t believe it. My heart somehow was always the opposite.”

“One Jew is responsible for the other one, we don’t know who’s fault it was,” she said.

At the war’s end, by some miracle, two of Anna’s brothers and two of her sisters were still alive.

The richest people in the world

“They always considered themselves the richest people because they were so happy with what has become their portion in life,” Craig Lustman, a grandchild of Jacob and Anna said.

As immigrants in a very secular, new world, Anna and Jacob insisted on instilling a Jewish identity into the family they were building. A big part of that was instilling a belief in never being ashamed of your Jewishness.

“We grow up with them as our heroes, our role models,” said Craig. “The stories we heard of them consistently, and their outlook on life after, their value system.”

Despite the horrific hurdles his grandparents faced, Craig said that his grandparents chose to view their circumstances as a gift to share with everyone.

“They literally felt like the richest people in the world. They had no money, no money growing up,” he explained.

His grandfather worked 3 jobs and his grandmother worked nights to help make end’s meet, but despite this they felt blessed.

“They had exactly what they needed, and for them, that was, especially coming out of the Shoah, the Holocaust … they felt on top of the world, they had everything they wanted.”

What they had was the value of time. Both who lost so many family members were able to rebuild in America and start a new family. Jacob passed away in 1996 and Anna in 2014, they are survived by two sons, seven grandchildren and 26 great grandchildren and one great-great grandchild.

Originally Published Nov 2, 2022 06:51AM EDT