News of Israel’s unprecedented victory in the Six-Day War stunned the world and even penetrated the Iron Curtain, inspiring a generation of trapped Soviet Jews to reclaim their Jewish roots. Young Natan Sharansky, forbidden from moving to Israel and reuniting with his wife, joined a force of Jewish human rights activists fighting for civil, religious, and cultural rights in the Soviet Union. Their courageous stance raised international awareness of the USSR’s social injustices. But could a few broken cogs in the Soviet machinery successfully dislodge the whole regime?

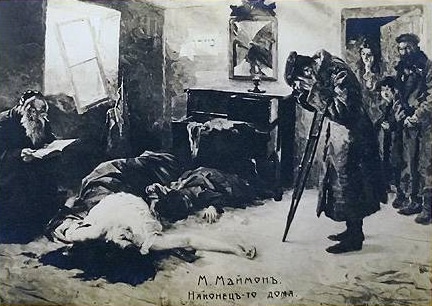

In the 19th century, Western European powers finally granted citizenship to their longtime Jewish residents, but Eastern Europe didn’t follow such liberal trends. Not only were Russian Jews not considered citizens, but from the 1880s to the 1910s, the Russian Czars instituted blatantly antisemitic policies and encouraged violent progroms that killed thousands of Jews.

Naturally, many young Jews, including 13 year-old Boris Sharansky, welcomed 1917’s communist revolution that sought to overthrow the Russian Czars. Boris and his peers subscribed to Karl Marx’s vision, believing that religious and nationalistic identities were the cause of hate and division. They believed that if Jews abandoned their identities to join with other revolutionaries, they could help create a utopian society.

The Czar stepped down in March 1917, and the Russian Provisional Government abolished all anti-Semitic measures. But this temporary government was short-lived. From October 1917 to 1921, Civil War gripped the land, with the White Army, which included a few diverse parties, fighting against the socialist Red Bolshevik army. Many factions of the White Army were violently antisemitic, waging more than 2,000 progroms that killed 150,000 Jews and left another half a million homeless. The Bolsheviks were outwardly against such anti-Semitism, attracting many Jews to join the Red Army. Yet when they won the Civil War and set up their own government in 1921, they aimed to forcefully assimilate the Jews.

Then came the Holocaust, in which two million of the 3.2 million Jews in the region were brutally murdered by the Nazis. Those horrors, combined with the generally deteriorating state of affairs for Russian Jews, had many eager to emigrate to Israel. This gave the Chairman of anti-Semitism, Joseph Stalin, another reason to hate Jews; he became infuriated by the potential negative press such a massive wave of emigration could create. He therefore refused to let the Jews emigrate and unleashed a new wave of anti-Jewish repression, pushing many Jews to assimilate further as a protective measure.

Thus when Boris Sharansky’s son Natan Sharansky was born in 1948, he grew up completely unaware of his Jewish history, religion, culture, or language. Like many others of his generation, Natan only knew that the status “Jew,” printed on all his formal identity papers, meant that his opportunities were severely limited.

When Stalin died unexpectedly, Sharansky’s parents were secretly relieved. Although Stalin’s antisemitism was public knowledge, most people couldn’t have fathomed the full extent of it. At the time of his death, Stalin had been organizing an elaborate scheme to ignite a new wave of pogroms and potentially exile Jews to Siberia. Sharansky, only five, was told to celebrate the death at home but obediently wept with other students at school who sang songs in Stalin’s praise. At that young age, he learned the art of hiding his true thoughts and feelings in order to fit into Soviet society.

On the eve of the Six-Day War in 1967, many non-Jewish Russians celebrated Israel’s near-annihilation. Israel’s Arab neighbors had not only been armed with Soviet weaponry, but had also been instigated by false Soviet reports of Israeli aggression. However, a remarkable turn of events happened: Israel not only survived the war, but gained important territorial victories. Many Jews, inspired by these events, were newly inspired to get to the Holy Land.

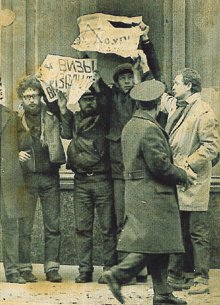

However, many leading Soviet politicians were virulent antisemites, and they barred Jewish emigration to Israel once again. “Refuseniks,” as the many Jews denied emigration were called, were usually fired from their jobs, resulting in both social and financial ruin. In 1970, 16 refuseniks attempted to hijack a civilian plane and fly it to Israel. Despite months of planning, the all-surveilling KGB snuffed out the plan and arrested the refuseniks before the plane ever took off. But the brazen act and its subsequent trial, garnered massive international awareness of the civil injustices of the Soviet state.

Sharansky, inspired by this tide of Jewish pride, began reading articles by Soviet dissidents. In 1973, he decided to try to make Israel his new home.

Sharansky was put on trial simply for his application to emigrate, which was where, for the first time, he publicly defended Israel’s moral position, as well as his desire to join the country. Still, his application was refused. Despite the restrictions his application earned him, Sharansky felt that, having spoken his mind at last, he was a free man, no longer enslaved by the Soviet system.

Sharansky was allowed to keep his position working in a government lab for another 3 years after his trial, but from then on, he dedicated every spare hour to public activism. His English proficiency proved an invaluable resource for corresponding with foreign journalists and making sure they were reporting the civil injustices of the Soviet state. He started out helping Jewish dissidents, but soon joined with non-Jewish dissidents as well. In response, many demanded he choose: was he a Jewish activist or a social rights activist? He strongly avowed that he was both, and only as a strongly-identified Jew could he help push forward the greater social cause.

In 1973, Scharansky met Avital Stieglitz, a strong-willed young woman who was also exploring her Jewish roots. He invited her to join an underground Hebrew language class he was in, and the two fell in love. Avital’s request to emigrate to Israel had been accepted, and the couple figured it was better that at least one of them start their life in their dream country. So the couple got married in their friend’s apartment, spent one day together as husband and wife, and then Avital flew to Israel.

As Sharansky spent over three years waiting to rejoin his wife, he became increasingly involved with reporting the USSR’s injustices to the foreign press. Soon enough, ruthless KGB agents began following him everywhere.

In 1977, Sharansky was arrested on trumped-up charges for “spying for the USA.” The KGB had offered to release Sharansky to join his wife, Avital, in Israel if he admitted guilt and helped the Soviets destroy the Jewish emigration movement. Sharansky staunchly refused to give into the Soviet scheme, and was sentenced to 13 years in jail and hard labor camps. During his long jail sentence, which included maddeningly-long stays in punishment cells, Sharansky was able to stay clear-headed by reminding himself that his struggle was part of the larger Jewish story, and his resistance was integral for the freedom of his people.

Sharansky’s dissident allies organized on his behalf, but it was his wife that really pushed their cause forward. She tirelessly met with religious and political leaders across the globe to explain her husband’s plight. Finally, by 1985, the USSR was significantly impoverished and living conditions were dire. The new Soviet ruler, Mikhail Gorbachev, was eager to work with the United States to both tone down the potential of nuclear war and rebuild his country’s economy. When he met with President Reagan in Geneva that year, Reagan told him that the world believed in Sharansky’s innocence and that the human rights situation in the USSR had to be ameliorated before the two countries could work together. The next year, after nine years in jail, Sharansky was released as part of an East-West prisoner exchange.

Sharansky flew to Israel and received a hero’s welcome. But he wasn’t content to simply enjoy his personal freedom. He quickly began rallying American Jews for the greater Soviet Jewish cause and on December 6, 1987, he organized the largest Jewish gathering in American history. Over 250,000 Jews, the majority of them Jewish housewives and college students, came together on the National Mall in Washington, DC, to protest the plight of Jews stuck in the Soviet Union. Soon after, Gorbachev caved, allowing for unlimited Jewish emigration. And against all odds, the Soviet Union itself was dissolved in 1991.

The fight for Soviet Jews, sparked by Jewish dissidents within the USSR, played a huge part in disrupting the corrupt communist regime. Natan Sharansky maintains that it’s the power of a strong identity that empowers a person to make truly positive changes in the larger world. When he and other Jewish Soviets stepped into their own Jewish identities, they were able to do more for Eastern Europe than they ever could’ve done had they maintained their assimilated statuses in the Soviet machinery.

As Sharansky writes in his book, Never Alone, “To have a full, interesting, meaningful life, you have to figure out how to be connected enough to defend your freedom and free enough to protect your identity.”