In honor of Black History Month, we’re looking back at the complicated history of the relationship between the Black and Jewish communities. From the post-Civil War era to the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, through the Crown Heights riots in 1991, Black Lives Matter and the struggle for racial justice today, the history is a complex one with both cooperation and conflict.

Here are 9 things you need to know about Black-Jewish relationship in the U.S. and where it could be headed next. (Please note, this is by no means an exhaustive list.)

1. Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington created a school to educate Black children in the South.

In 1910, Julius Rosenwald — the Jewish philanthropist and president of the Sears, Roebuck and Company department stores — read a book by Booker T. Washington, an educator who started his life as a slave and eventually built up the illustrious Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. It was the start of a remarkable collaboration between the two men.

Public education for Black children was chronically underfunded in the segregated schools of the South. Over a span of two decades, Rosenwald and Washington built 5,000 schools that educated more than 600,000 Black children — approximately one-third of all Black children at the time — in what became known as the Rosenwald School Project. Washington also engaged with the Jewish community, speaking at synagogues around the country.

2. The rise of the Nazis and the Holocaust led the two communities to unite and advocate for each other.

Notwithstanding Rosenwald and Washington’s extraordinary partnership, there were also significant divisions between the two communities. Many Jews were influenced by the general racism of the time, and Black people by the antisemitism. (Learn more about the tensions between the two communities in our video.)

But in the 1930s and 1940s, the divisions between the two communities largely fell by the wayside with the rise of a new force in the world that united both communities.

In the wake of the Holocaust, many Jews and Jewish institutions recognized they had a common cause with the Black community in the fight against bigotry. Black organizations were eager to join forces with Jewish organizations, not only because the Nazis were horribly racist, but because Black Americans realized that Jews were also a vulnerable minority.

Ultimately, the horrors of the Holocaust pushed each community to acknowledge that they shared a common vision for the future: a world devoid of hatred and discrimination where all people can live in freedom.

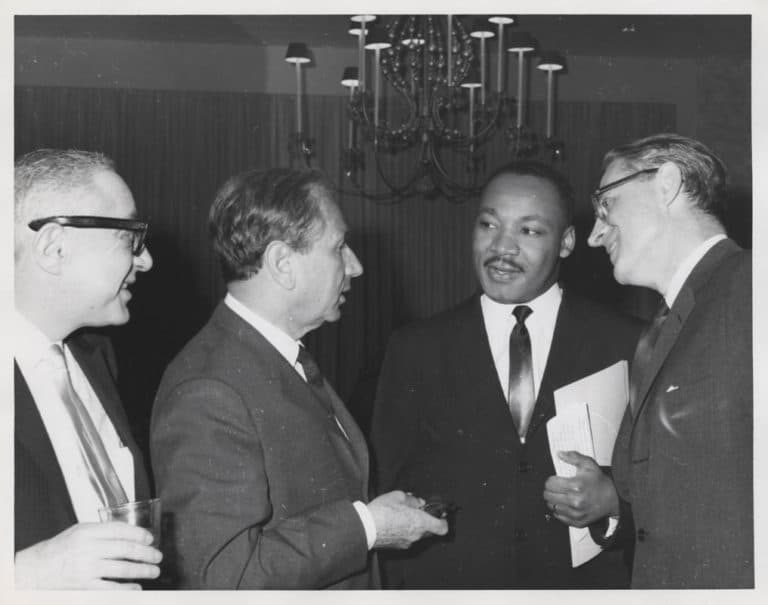

After the war, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. expressed this sentiment in a speech at the American Jewish Congress Convention in 1958:

“My people were brought to America in chains. Your people were driven here to escape the chains fashioned for them in Europe. Our unity is born of our common struggle for centuries, not only to rid ourselves of bondage, but to make oppression of any people by others an impossibility.”

3. Rabbi Joachim Prinz delivered a speech at the 1963 March on Washington just before Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

The relationships developed during the first half of the 20th century created the foundations of significant partnerships between the two communities during the civil rights movement. Many Jewish leaders, such as Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel and Rabbi Joachim Prinz, were involved in the fight for justice and equality for Black Americans.

At the famous March on Washington on August 28, 1963, Rabbi Joachim Prinz delivered this speech right before Dr. King gave his famous “I Have a Dream” address. In his speech, Prinz reflected on his experience serving as a rabbi in Germany as the Nazis came to power.

Prinz underscored that the most important thing he learned was that the most urgent problem is not bigotry and hatred, but silence in the face of hate. “America must not become a nation of onlookers” in the fight against racism, Prinz told the crowd. “America must not remain silent. Not merely Black America, but all of America…must speak up and act.”

4. In 1964, the murder of two Jewish activists — who were helping to register Black voters in Mississippi — prompted national outrage.

In 1964, as part of a campaign called the Freedom Summer Project, volunteers from across the country traveled to Mississippi to help register Black voters. Black and white college students from the North, with a disproportionate number being Jews, were bussed down for the effort.

Early in the summer, two Jewish activists from New York City, Michael Schwermer and Andrew Goodman, and one local activist, James Chaney, were arrested by a sheriff who was also a member of the Klu Klux Klan. Shortly thereafter, all three were driven to a deserted area and murdered by a group of Klansmen.

While the murder of Black men in the South rarely made national headlines, news of the murders of two white activists further publicized the unchecked, institutional violence of Southern segregationists.

5. Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel marched with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama in 1965.

In 1965, Dr. King led a civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, a theologian and professor at the Jewish Theological Seminary, participated in the march.

When Heschel returned from the march, someone asked him, “Did you find much time to pray when you were in Selma?” Heschel reportedly responded, “I prayed with my feet.”

Heschel, who joined King in many speeches and protests, famously said: “Racism is man’s gravest threat to man, the maximum of hatred for a minimum of reason, the maximum of cruelty for a minimum of thinking.” At one point, Heschel also called King “the voice of God in our time.”

6. Black leaders like W.E.B. Du Bois and Martin Luther King, Jr. were vocal supporters of the Jewish State.

In the wake of World War II, prominent Black activists and organizations began advocating for Jewish interests, including the Jewish right to self-determination in their historic homeland.

Black scholar and diplomat Ralphe Bunche led the U.N. commission charged with setting up the young Jewish state. Although he was hailed as a hero by the Jewish community, a year later, historian and activist W.E.B. Du Bois criticized Bunche for not sufficiently championing Jewish interests in the Holy Land.

Dr. King was also an outspoken advocate for Israel’s security: “Peace for Israel means security, and we must stand with all of our might to protect its right to exist, its territorial integrity,” King said at the Rabbinical Assembly convention in 1968.

“I see Israel…as one of the great outposts of democracy in the world…Peace for Israel means security and that security must be a reality,” he added.

7. The Crown Heights Riots in 1991 was one of the lowest points in the relationship, but it led to 30 years of reconciliation efforts.

One of the lowest points in the relationship was the Crown Heights Riots in 1991 when tensions between the Black and Jewish communities exploded into three days of riots directed against the Jewish community.

Tensions had been growing for years in Crown Heights, a Brooklyn neighborhood shared by Black and Jewish residents. On August 19, 1991, a driver in the motorcade of the Lubavitcher Rebbe (the leader of the Chabad movement) lost control of his car and hit two Black children, killing one of them.

At the same time, crowds of West Indian Brooklynites spilled onto the sidewalk from a reggae concert and began to gather around. When the local Jewish ambulance service, Hatzolah, arrived, police reportedly ordered the crew to take the driver to safety (a city ambulance was on the way for the children).

When the crowd saw the ambulance pull away with the Jewish driver, leaving the two children on the ground, tensions between the communities exploded.

Shouts of “Kill the Jew!” could be heard from the streets, and later that night, a 29-year-old Hasidic man, Yankel Rosenbaum, was stabbed to death.

Riots swept through Crown Heights for three days. Mobs of young Black men roamed the streets, targeting Jews and Jewish businesses, ambulances, and police. The violence shocked the Jewish community. Historian Edward Shapiro wrote: “It was the only riot in American history in which the violence was directed at Jews.”

In the aftermath of the riots, members of both communities realized that healing and cooperation were the best path forward. Against all odds, Black and Jewish leaders found commonality in the need to rebuild their shared space.

In one memorable event, a Jewish teacher named David Lazerson and a Black teacher named Paul Chandler brought together young Jewish and Black residents of Crown Heights for a public conversation.

“We got them talking, and the questions were like, ‘Why do you have dreadlocks, and why do you have a hat on your head?” Lazerson recalled from that first meeting. “We really didn’t know anything about each other.” As the talks progressed, the group formed a Black-Jewish basketball team and music band.

Thirty years after the riots, the annual “One Crown Heights” event stands as a testament to the enduring efforts of Black and Jewish Americans to see the humanity in each other and build a better community together.

8. We all have a role to play in fighting against racism in our communities.

According to the 2020 Pew Research Center survey, 15% of American Jews aged 18 to 29 identify as Hispanic, Black, Asian, multiracial, or some other race or ethnicity, compared with just 3% of American Jews aged 65 and older.

As the Jewish community becomes more ethnically and racially diverse, a survey of Jews of color —released in August 2021 — suggests that we have work to do to create communities that are inclusive and free of racism.

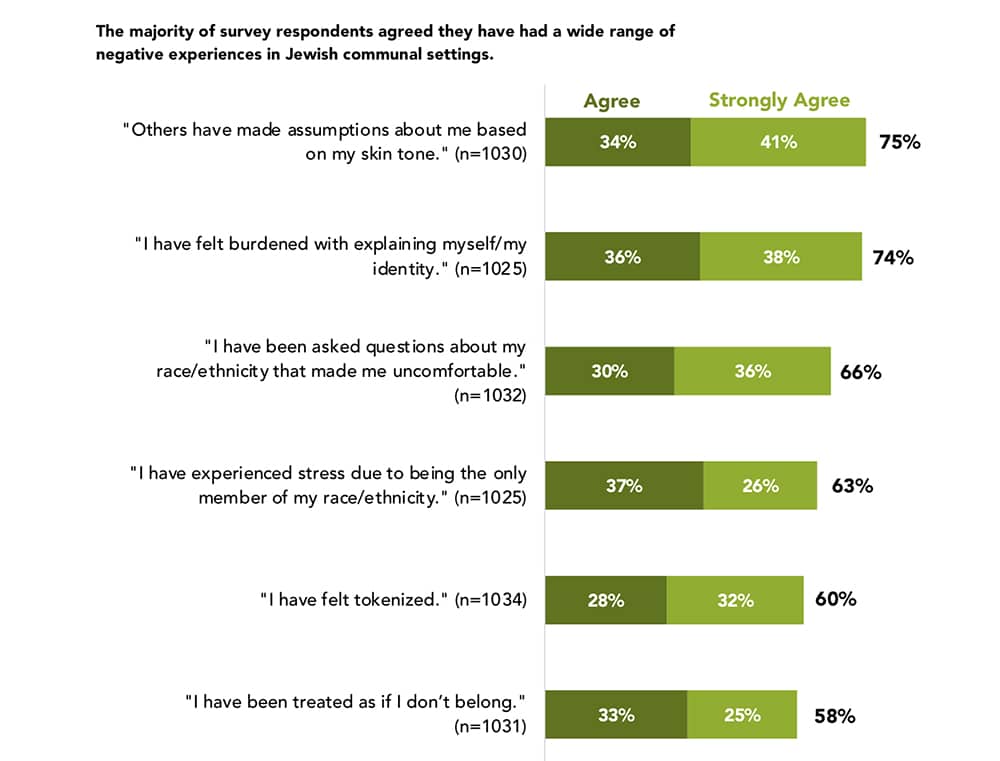

The survey, titled “Beyond the Count,” found that 80% of the respondents said they had experienced discrimination in Jewish settings. Additional results from the survey are shown in the graph below:

Ilana Kaufman, executive director of the Jews of Color Initiative, which commissioned the study, said: “This study validates the experiences of Jews of color, and it also takes away a bit of the illusion that Jewish community organizations are doing enough to respond to racism and racial injustice.”

We recently asked Kylie Unell, a dean’s doctoral fellow at New York University, studying German Jewish philosophy, for her thoughts on this study and if she has experienced discrimination in Jewish settings.

Unell saw this differently: “I’ve experienced people saying stupid things. It’s hard to classify what it is — what is discrimination? I want to say I have faced pain, feeling like an outsider in the Jewish community…wanting to feel like I fit in.” Listen to the entire conversation with Unell on our podcast, “The Power Of.”

9. What is the state of the relationship between the communities today?

So, now that we’ve explored the history of Black-Jewish relations in America, how should we assess the state of the relationship today? And what will the relationship look like in the future?

The relationship between the Black and Jewish communities today is complicated, characterized by both cooperation and conflict.

On the positive side, in 2019, a bipartisan group of Congress members announced the formation of the Congressional Caucus on Black-Jewish relations “with the hopes of strengthening the trust and advancing our issues in a collective manner.”

Additionally, with the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, many Jews are taking active roles in the continuing struggle for racial justice today, as the Jewish community did during the civil rights movement.

On the other hand, antisemitism has been on the rise in recent years, including in parts of the Black community. In 2019, two Black men — one of whom was connected to an antisemitic hate group — murdered four people in a kosher supermarket in Jersey City.

In 2020, several prominent black athletes and entertainers, including DeSean Jackson, Stephen Jackson, Nick Cannon and Ice Cube, made antisemitic statements or posted them on social media. (All but Ice Cube subsequently apologized.)

In 2022, Kanye West spewed antisemitic comments to his 50 million followers, basketball player Kyrie Irving shared an antisemitic film, comedian Dave Chappelle reinforced antisemitic tropes on SNL, and members of the Black Hebrew Israelites spewed antisemitism in support of Kyrie Iring.

Additionally, Israel can be a divisive topic today, especially between Black and Jewish Americans. With Black Lives Matter activists increasingly using their platform to denigrate Zionism, many believe the Black community is growing increasingly anti-Zionist and antisemitic.

What will it take for the two communities to overcome these divides?

Here’s how two professors of Jewish studies, Ethan Katz and Deborah Lipstadt, responded to that question: “To advance the cause of Black-Jewish relations today, the great challenge is for voices of compassion and mutual respect to rise above the prevailing din of acrimony, misunderstanding and distrust.”

“Such voices should begin with a greater understanding of both Jews’ and Blacks’ complex, often painful histories and how the past has shaped each group’s collective identity,” they added.

“And they would also do well to recall…when many Jews and Blacks stood shoulder-to-shoulder — and in some cases gave their lives together — in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s…In this moment, many Blacks and Jews found their commonalities more notable than their differences,” Katz and Lipstadt concluded.

Similarly, in a CNN op-ed, Professor David Love of Rutgers University called on the two communities to recognize the positive moments in their shared history, such as “the liberation of concentration camps by Black soldiers, Jewish refugees such as Albert Einstein teaching at historically Black colleges and universities, and the participation of Jews in the Civil Rights movement.”

Love also called on schools to teach about the history of racism, antisemitism, and other forms of bigotry in the U.S. “Far too often, this [history] is glossed over or rarely and inadequately taught in school, resulting in people speaking and reproducing antisemitism through ignorance,” he wrote.

Originally Published Feb 1, 2023 09:02AM EST