Welcome to part two of our three-part Yom Kippur War series. If you haven’t listened to the last episode, go back and listen, please! You’ll need the context to understand this episode, which takes place almost entirely on the battlefield.

All caught up? Let’s get to it, then.

You might be familiar with this line from the Passover seder, originally from the Talmud, Tractate Pesachim, page 116b: “In every generation, each person must see themselves as though they left Egypt.” “בְּכָל־דּוֹר וָדוֹר חַיָּב אָדָם לִרְאוֹת אֶת־עַצְמוֹ כְּאִלּוּ הוּא יָצָא מִמִּצְרַיִם…”

And honestly, I think that’s a pretty good directive for how to live your life, for how to live life in general, on Passover or any other day, whenever. Because the Talmud is telling us: imagine yourself in someone else’s shoes. Imagine you were there. It’s an important exercise in empathy.

In this episode, we tried our best to put ourselves in the combat boots of a shocked Defense Minister, in the sensible grandma-shoes of the Prime Minister, in the regulation army boots of a teenage tank gunner who never expected to see combat, in the house slippers of a mother who has just been told her only child was killed in action, or taken prisoner, or horribly wounded.

We’ve put ourselves in the shoes of an entire country staring down the threat of annihilation. And these shoes, well, they’re highly uncomfortable. They pinch and they rub and they leave blisters, and yes, I’m getting a lot of mileage out of this metaphor.

So if this episode is hard to listen to — well, good. We want you to feel it. We want you to know what it was like to be Defense Minister Moshe Dayan as he stood in IDF’s northern HQ before sunup on October 7th, 1973, as a young commanding officer ruined his day…

Chapter Two: Who By Fire

Dawn hadn’t yet broken when Dayan arrived at headquarters up in the north. The news was as dark as the sky. The IDF’s defense in the southern sector of the Golan had collapsed. The Syrians had advanced halfway to the Jordan river. The reserves wouldn’t arrive until at least noon.

Dayan’s autobiography, published three years after the war, recounts this moment with a surprising detachment. The Syrians were here. We were there. The situation was bad, but we turned it around. His retelling leaves out his despair. Leaves out any hint of emotion at all, and listen, autobiographies are kind of biased. So we turned to another source, Abraham Rabinovich’s history of the Yom Kippur War, which offers a much more poignant perspective.

Later that day, as the IDF fought furiously to keep the Syrians from reaching the kibbutzim of the Jordan Valley, Dayan found a moment to watch the battle. He was too far away to make out the tanks or the guns, but from his perch overlooking the Hula Valley, he could see the columns of smoke, the flashes of light that signaled another missile, another bomb, another downed Israeli plane. He could hear the explosions that could have meant anything. Every sound, every flare, another potential casualty. Another boy that would never come home.

He stood there until the tears blurred his vision. But nothing could stop the nightmarish reel looping over and over in his head: The Third Temple is falling. The end is here.

But as we mentioned at the end of the last episode, Israel had an ace up its sleeve. Golda called it varenye, the jar of preserves stashed at the back of the cabinet for the leanest times. But Dayan was much more plainspoken. Later that night, he informed the Prime Minister that he’d taken the liberty of calling up the director-general of Israel’s Atomic Energy Commission. The man was waiting outside her office. Did she want to give her approval for a little nuclear demonstration?

I want to pause right here. Because this is freakin’ wild, and it’s not the last time that nukes show up in this story.

Back in the 50s, David Ben Gurion pursued nuclear technology as a worst-case scenario, ultimately for deterrence. But Israel’s first prime minister was smart. He knew that if Israel flaunted its nukes, the Arab states would start an arms race, leading to a fully nuclear Middle East and mutually assured destruction. No one wanted that. So Israel’s official policy on the nukes was one of ambiguity, or in hebrew, amimut.

Dayan was breaking protocol by referring so baldly to the open secret in Dimona. Now, he wasn’t necessarily suggesting that Israel nuke Syrian or Egyptian cities. But a “demonstration” — most likely over an unpopulated stretch of the Sinai desert — would show that Israel meant business. The Jewish state may have been taken aback by the surprise attack on Yom Kippur, but it could handle itself.

But Golda’s two most trusted advisors, who were in the room at the time, said no way, Jose. (Direct quote, probably.) And so Golda declined to authorize any kind of nuclear demonstration — undoubtedly a wise move, given that this was smack in the middle of the Cold War and the entire world was on edge watching the Soviets and the Americans flirt with starting WWIII. Which they almost did, as the Yom Kippur War continued.

But we’ll get there, hold your horses. So the men in the Sinai and the Golan continued to fight, not knowing that their country’s defense minister had just proposed a nuclear option. It would take many more deaths before Israel managed to turn things around. And the worst was yet to come.

Dayan had visited both fronts in the first days of the war. And what he saw in the Sinai horrified him even more than what he saw in the Golan. No one had predicted the intensity of Egypt’s opening salvo. Within sixty seconds of their initial assault on October 6, 1973, the sands of the Sinai were littered with ten thousand Egyptian shells. As Rabinovich writes, quote, “Not since the construction of the Pyramids…had Egypt seen such a massive and well-executed enterprise.”

The Egyptians’ discipline came as a shock. Back in ’67, the IDF had sent the Egyptians packing with their heads hung low and their tails between their legs. High on their stunning victory, the Israelis never considered that the enemy might adapt. Might become stronger. Might learn something from its failures.

From your ordinary Yossi up to the Chief of Staff, everyone assumed that if the IDF ever had to fight another war, they’d be facing the same armies they’d routed so easily in 1967. They were wrong.

Orit Shacham-Gover was an intelligence officer during the Yom Kippur War. Decades later, she recounted her experience in the excellent Israeli documentary “Lo Tishkot Ha’Aretz.” The English translators chose to call the documentary “The Avoidable War.” But the literal translation of the title is “The land will not be quiet,” and I like that a lot better.

“The Avoidable War” is sterile. The Hebrew title, though, isn’t pulling any punches. 2,656 Israeli soldiers were killed over the 21 days of the war — half of those within the first three days. Over 7,000 Israeli soldiers were injured, and nearly 300 taken prisoner, with some tortured or killed in custody. The sands of the Sinai and the hills of the Golan were soaked with blood. So no. The land wasn’t quiet. It was screaming. And all of Israel screamed with it, in bitter, bloody surprise.

This wasn’t supposed to be happening. Hadn’t Israel fought enough? Hadn’t it paid the price, over and over and over again, for living in this tiny, fractious sliver of land? Hadn’t it proven itself to its neighbors?

Call the post-1967 concepzia “euphoria.” Call it “hubris.” Within days, it was shattered. Every family dreaded the knock on the door. The solemn-faced soldiers in their fatigues, we regret to inform you…

It was the Jewish holiday season. The harvest festival of Sukkot was due to start. The streets should have been thronged with people celebrating the holiday of Simchat Torah. Instead, the entire country mourned.

Orit said later: “I remember this feeling of, we’re the chosen ones. There was this feeling that we could do anything. We as a group, we as a society, we the Israelis — we can do anything. Arabs are all pathetic, cowards, weak, running barefoot through the desert. These were the pictures, the images, that we grew up on. We waited, on Yom Kippur, to see these poor weak Arabs who ran barefoot through the desert. And they weren’t there. It was us, in some cases, running barefoot through the desert.”

The Egyptians had been preparing for their moment for six years. They were precise. Organized. Disciplined. Armed to the teeth with Soviet weapons. And — perhaps most importantly — they were mad as hell. They’d lost in ’67. Spent three years harassing Israeli forces in the Sinai, hoping and failing to regain an inch of territory, a scrap of dignity. Their economy was crumbling. Their national pride was gone.

This was their last chance to show up the tiny upstart neighbor who had caused them such grief. They all knew they were taking a risk. If they lost again, there would be no coming back from the shame. So they made darn sure they didn’t lose.

Two things separated Israel and Egypt. The first was the Suez Canal. The second was the Bar-Lev line: an Israeli-built system of fortifications stretching 100 miles along the canal, interrupted only by the poetically named “Great Bitter Lake.” Most of Israel’s defense establishment thought the Bar-Lev line, and I encourage you to Google it, by the way, would hold for at least a day – enough time to slow down the Egyptians and mobilize Israeli reservists to repel the attack.

The IDF wasn’t entirely naive. They’d been practicing for the unlikely prospect of an Egyptian attack on the Sinai, and they won those war games handily, satisfying nearly everyone that the Bar-Lev line would hold and that Sadat ultimately wouldn’t gain an inch.

But remember, they were fighting those war games against an entirely different enemy.

These were not the Egyptians of ’67. And the Bar-Lev line was not some impenetrable fortress. In the words of Abraham Rabinovich, the name “Bar-Lev line,” quote, “conjured up an image of massive interlocking fortifications… In fact, it was a string of small, isolated forts, each with garrisons of only twenty to thirty men. There were miles-wide gaps between the forts…” The Egyptians blasted through these gaps in mere hours, planting their flags on Israeli forts.

You gotta remember, Israel is small. Like, really, really small. When your country is roughly 290 miles long and 70 miles at its widest point, every battlefront is uncomfortably close to a population center.

Nerd corner alert: if we’re counting the West Bank and Gaza, then at its widest point, Israel is still only 85 miles across — i.e., not wide at all.

That’s why the IDF’s strategy, historically, had been: push out the invaders as quickly as you can and go on the offensive. All of the IDF’s battle plans focused on counterattacking, glossing over the finer points of, you know, defense.

But they couldn’t counter-attack just yet. They could barely even defend themselves! The Israeli tanks that rolled out to meet the Egyptians were met with a volley of bullets, RPGs, and long-range anti-tank Sagger missiles. I have no idea what a Sagger missile is, by the way. But it sounds really scary. And when the Israeli tanks swerved to avoid fire, they hit the land mines that the Egyptians had laid in their wake. It was a horrifying image.

Lt. David Abudaram had one mission: Just. Hold. On. For 24 hours, or until his backup came. And he did, but it cost him. “I guess there was an RPG. It took my whole shoulder, right here, and I started bleeding. The bleeding was awful. Here. In this part. I saw it, and only then did I understand that I was wounded. And then I look to my left. There were two guys… I saw how they took an anti-tank grenade to the neck. Their heads were…slaughtered. You see the arteries. The way the blood runs through them. It’s a picture you can’t forget.”

And yet, the men on the field continued fighting, even as tanks exploded around them, as their boats caught fire, as shrapnel shredded their skin.

Even the Egyptian Army’s Chief of Staff, Saad eh-Din Mohamed el-Husseiny el-Shazly, and yes that is an amazing name, much cooler than Noam Weissman, took note of this remarkable bravery, writing in his diary, “Through the night, commanders of Israeli subunits, even individual tanks, fight on. They are evidently made of better stuff than their commanders.” As grim reports poured into their war rooms, IDF commanders were shocked, even paralyzed.

And I don’t blame them for a second. The Israeli top brass had a schema — basically, a model they used to organize information. And in that schema, the Arab armies, though belligerent and aggressive, were ultimately pathetic, no match for the tiny but mighty IDF.

Any psychologist can tell you that challenging a schema is really difficult. It’s hard to change people’s minds. But within hours of the initial attack, the IDF’s top brass not only had to re-organize the way they saw the world — they also had to confront the fact that their prior schema had led to an ever-spiraling body count. They needed to regroup, and fast. The fate of the country was at stake.

Down in the Sinai, the Egyptians were delivering what we might call “a thorough butt-kicking,” and yes, that’s an official military term. Now, you might be asking, where was the air force? Why couldn’t they take out some Egyptian tanks from above? After all, the Air Force had more or less won the Six-Day War by demolishing Egypt’s air force in the first three hours, leaving the skies clear for Israeli jets.

But — are you sensing a theme here, yet? This wasn’t 1967.

True, on the first day of Yom Kippur War, the IAF took down a number of Egyptian planes above Sharm el-Sheikh, the beautiful coastal enclave on the southern tip of the Sinai Peninsula. But they found out the hard way that they couldn’t help even the score on the ground.

I’m going to play you a recording from Day 2 of the war. You’ll hear a desperate conversation between Shaul Moses, commander of a tank division in the Sinai, and his sergeant, Shlomo Arman, who was himself in a different stronghold roughly 15 miles away, and he wouldn’t live through the next day.

It’s a little bit hard to hear, especially because I’ll be translating. But if you can, turn up the sound a little bit. Listen to the way Shaul’s voice shakes as he asks for help: “The enemy is in the stronghold. We are in need of help. Is someone able to send it to me? Roger, over.”

Arman’s response is just as upsetting. Can you hear the anguish in his voice as he issues the orders? “Help is on the way. Overcome them, attack them, and kill them. Attack them inside the stronghold. Over.”

Shaul got the help he needed when four Air Force Phantom jets showed up to bomb the enemy. But his soldiers’ glee turned to horror as — well, I’ll let him explain what happened next.

Four decades later, he can’t recount the story without crying: “The planes came because we asked them to. We felt responsible for that. We saw the missiles — how the missiles came up towards the planes. We started giving directions to the planes, as though they could hear us. Turn right, turn left, there’s a missile behind you! Every few seconds, another Phantom would fall, until we asked to call it off.”

The Soviets had supplied Egypt with surface-to-air missiles. And at the time, it didn’t really matter how good a pilot you were, or how much you’d practiced, or how cleverly you maneuvered when there was a guided missile coming towards you.

It was theoretically possible to avoid a guided missile. The U.S. Air Force had been practicing exactly these kinds of evasive maneuvers in the skies above Vietnam. American pilots called these maneuvers “Dancing with Death.”

But the IAF hadn’t expected guided missiles. They hadn’t had time to practice their dance moves. And so death led them on a waltz through the skies and into the sands.

I can’t imagine what it was like to wait with such hope for the legendary Israeli Air Force to show up, and then to watch as plane after plane went up in a ball of flames and fell out of the sky. To hear the shriek of a missile, the boom of impact, and watch the wreckage fall to earth. And to keep fighting despite that.

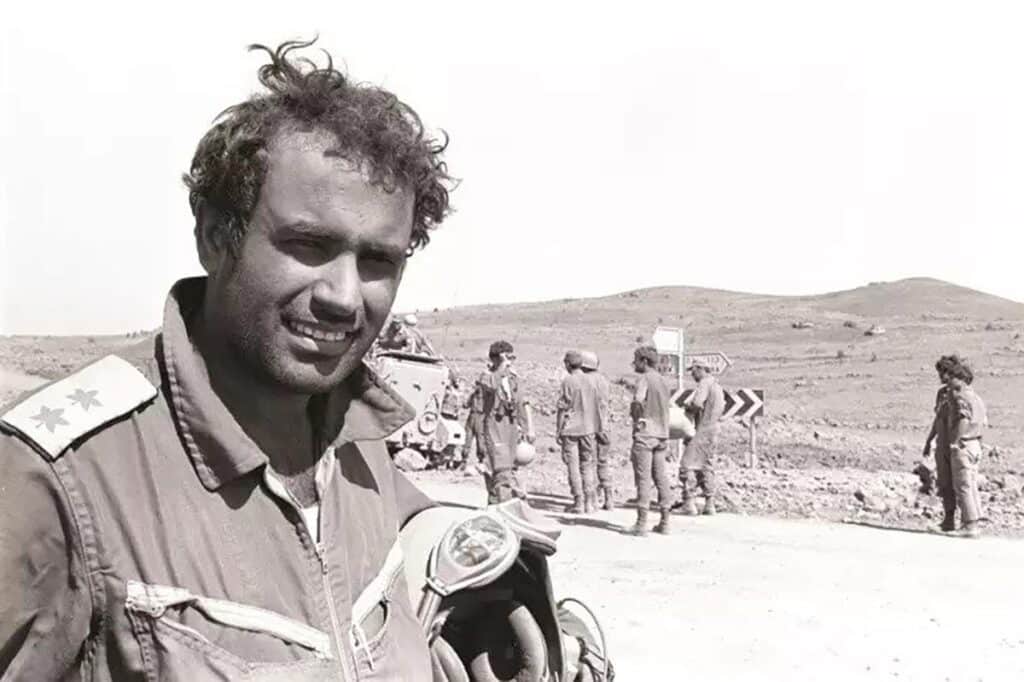

So we asked the legendary Avigdor Kahalani, yes, that Avigdor Kahalani, who you already heard from in the last episode, and whose story you’ll hear in a second, to explain how it was possible for these young men — some of them still in their teens! — to carry on despite the overwhelming odds.

It feels a little weird to ask someone why they weren’t more scared. To wonder, out loud, what kept them fighting as they watched their friends die horribly before their eyes. This is what he said.

“In Israel, everybody feels that he’s holding the flag of the country. And one day, he had to prove that he can do it. And my soldiers at that time, they ran like crazy to fight and to stop them. And I got the courage from them.”

“It comes from kindergarten, and after, elementary school and high school. All the time, we studied our Bible and our roots and the Holocaust — the whole picture. And it comes one generation to another generation, they give a mission that one day you’ll have to protect your country. And this is exactly what we have done.”

The Egyptian forces might have been motivated by their shame and humiliation, by their love of their country and their desire to regain respect. But their anger was only six years old. Okay, maybe 25 years old, if you’re also counting 1948.

But the Israeli soldiers, they were motivated by the long arc of Jewish history. By an ancient connection to their homeland that even two thousand years of exile couldn’t sever. The modern state of Israel was only a quarter of a century old, but the Jewish people had been fighting for their land ever since Joshua led the Israelites into Canaan in the 2nd millennium BCE.

But you don’t win a war with ideals alone. You win by strategizing. By adapting quickly to the challenges. By mobilizing your backup. By sheer chutzpah. You win because you have no other choice. As Egypt delivered blow after blow in the south, Syria pummeled the northern front. Israeli forces were desperately outmanned. Even as they took out Syrian tanks, firing with stunning accuracy and speed, Assad’s army kept on coming.

Here’s Kahalani again, describing the first 24 hours on the northern front. This is a fragment of what Moshe Dayan saw as he stood in the Hula Valley on the afternoon of October 7, 1973.

“The first night, I remember they crossed the border. They put many bridges over the tank ditch, and a lot of minefield, and they bomb everything, and they came close to us. And I remember this night because, at first, I was surprised to see how they are going to fight for the Golan Heights.”

“At that time, I didn’t have a solution to the situation. Because when they came during the night and I didn’t have any ability to stop them because they use infrared system. Infrared system, they can put the projector straight to your face and you don’t know that you are in the light. And they shot many and they hit many of my tanks. And try to understand the situation that most of my soldiers, they’re 18 years old, just finished the training. And just four or five months in the army. And the commander maybe is like 19 years old. And they called me and said, “Sir, we cannot stop them. We cannot stop them.” And all the time, another tank was on fire. And I’m the commander, and I have to lead them to give them hope that we can do it. And at this moment, I didn’t have any support from anything. No artillery, no air force. And we couldn’t use our projector to identify them.”

In other words, the Syrians had more men, more weapons, and the ability to see and aim in the dark. In contrast, the Israelis were sitting ducks. As soon as he realized that the Syrians could see his men clear as day, Kahalani instructed all his soldiers to turn their tank lights off immediately. And then the two sides began a complicated, intimate dance. “And they moved between my tanks and sometimes like that, and I found myself five feet around my tank was Syrian tanks.”

We’ve reflected before on the strange intimacy of enemies. Go back and listen to our episode on Sadat in Jerusalem for more on that. But I don’t know if I’ve ever thought about how that same intimacy might apply to a battlefield. How the enemy comes so close that you can look into his eyes.

And when you do, you may often see — yourself. So often, Israeli and Arab soldiers looked alike. The Israelis who had grown up in Arabic-speaking homes even shared a mother tongue with the enemy, though their dialects and accents often differed. And as you’ll hear in the next episode, both sides would have cause to reflect on their similarities by the end of the war.

But the war was nowhere close to over. And now was not the time or place for sentimentality. As the battlefield swarmed with tanks, young commanders made split-second decisions about when and where to fire, knowing they were desperately outgunned.

And I don’t know if there was room, in the heat of battle, to think about what would happen if they failed. But 50 years later, we can entertain the counterfactuals, and they aren’t pretty. As Rabinovich puts it:

“The future of the Golan rested not on the elaborate contingency plans prepared by the general staff but on improvisation against odds of 9:1. No scenarios existed in Israel for a battle fought under such conditions. In the end it would all come down to the instincts, individual and collective, of the officers and men fighting in the darkness.”

It was these instincts that saved the Israelis on the northern front. As Kahalani told us, “I gave them the feeling that if we will shoot the direction where they come from, give them the feeling that all the Israeli army waiting for them. And during the night when you shoot with the tank, it’s a big fire around and noisy. And this is what happened. And we gave them the feeling that we are here. We strong enough to protect ourselves.”

You don’t win a war just by bluffing. But sometimes, you can win it with sheer determination. For every shell the Syrians were able to fire, the Israelis fired two. They may have been massively outnumbered, but they weren’t going down without a fight. No better example exists than the story of 21-year-old tank commander Zvika Greengold, who, together with the soldiers in his tank, held off the Syrians’ 452nd tank battalion almost single-handedly.

For twenty hours, Greengold neutralized tank after Syrian tank, communicating only that his situation “wasn’t good.” Understatement of the year. But he assumed the Syrians were listening, and he couldn’t let them know that they were being harried not by an entire company but by a single tank.

It’s one thing to be brave when you know you’re winning. It’s another to be brave when you’re almost sure to lose.

This was the same bravery that allowed Kahalani to fend off the Syrians on the morning of October 9th, 1973. The war was three days old. And the disparity between the two sides was massive. “We had a problem that they crossed the border. More than 160 tanks. We’d been like 10 tanks, 11.”

“And I had a problem of… What we call leadership problem. How to lead my soldiers and to invade to the hills. That, from these hills, we can stop them. And we use the hills to stop them. And I had a problem to motivate them to move. They scared. Everybody’s scared in the war. Even me, of course. But they stuck in the moment. in the place, and they couldn’t move because they’re scared. And I had to motivate them to move forward and to be on the top of the hills before they will come with 160 tanks.”

He reminded his men that this was the same enemy they’d defeated before. And then, he led by example, moving first into the breach. To conserve ammunition, he ordered his men to shoot only at moving tanks.

Between October 6th and October 9th, he and his men repelled wave after wave of Syrian tanks in a fight that would become known as The Battle of the Valley of Tears. Or, as Kahalani put it in the heat of battle, “This valley is beginning to look like Lag B’Omer” — a reference to a Jewish holiday that involves lighting bonfires. Abandoned Syrian tanks littered the valley.

On the Israeli side, the cost was high. “The end of this combat, we survived like three tanks, no more than that.”

Remember — every tank held four soldiers. Losing a tank meant often losing the men inside it. Some burned alive. Some maimed beyond words. Some able to escape, hobbling towards the illusion of safety. And some surrounded by the enemy, emerging from a ruined tank with their hands up, walking into a scenario that might well be worse than death.

So when Kahalani says that only three tanks survived, he’s not just referring to weaponry. He’s talking about the human cost.

And still, he’s grateful. Because the results were miraculous. “We stop all of them. The result of this combat was unbelievable. And I believe God protect us.” With only a few tanks left, he and his men watched the Syrians retreat.

You don’t have to believe in God to understand Kahalani’s perspective. Who could have imagined that this tiny, vulnerable force would hold off the Syrians for so long?

Later that day, the Israeli Air Force took the fight to Damascus and bombed the Syrian army’s HQ. And within five days of the initial invasion, Israel would launch a counter-offensive, advancing into Syrian territory. They’d end the war with their tanks positioned 21 miles from Damascus, forcing Syria to accept a ceasefire for the third time in 25 years.

The northern front in the Golan stabilized well before the southern one. But the campaign, and the comeback, in the Sinai was no less impressive. The southern front was bleeding.

But Defense Minister Moshe Dayan knew that his gloom-and-doom predictions of a “fallen Third Temple” had seriously demoralized the Israeli cabinet. Dayan was as aware as anyone of the power of a good story. After all, it was a good story about Israeli invincibility that got the Jewish state into this mess.

And so, by the night of October 7th, he had dried his tears and told the cabinet, quote: “We’ve got to smash the Egyptian armor as soon as possible and also [smash] the new legend that’s beginning to be woven about the Arabs having become phenomenal warriors… A nation doesn’t change in six years. Individuals change. Not nations. This is not just a war of armor but a serious war of nerves.”

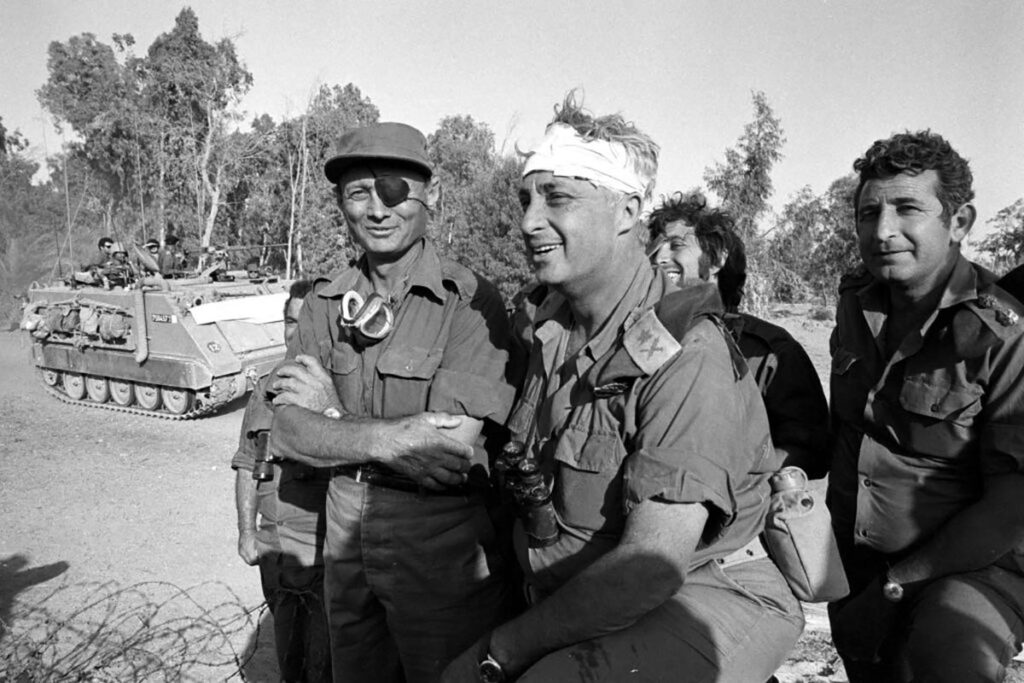

If there’s one thing Israelis have in spades, it’s nerve. And perhaps the best-known, and most controversial, exemplar of this characteristic Israeli chutzpah was Major General Ariel Sharon.

Maybe you remember from our Qibya episode that Sharon had been considered both brilliant and quite controversial (controversial might be a euphemism) since the founding of the state. Back in ’56, he’d almost been court-martialed for defying orders, launching an ill-planned attack on the Mitla Pass that cost the lives of 38 Israeli paratroopers. (Stay tuned, because the Mitla Pass is about to show up again in a big way.)

But sometimes, when your back is against the wall, you need an attack dog to go on the offensive. And this attack dog, whatever his flaws, was tactically brilliant. So though he was officially “retired” from army life, busy founding the Likud party under the leadership of Menahem Begin, Sharon quickly assumed command of the Sinai’s central sector.

He left for war at 2 am on Sunday, October 7th — just hours after the fighting broke out. And, nerd corner alert, he arrived at the front line in a civilian pickup truck painted with the sign “Ray of Light Solar Heaters.” Can you imagine that? The Israeli mobilization was so haphazard that generals arrived at war in their buddies’ cars. Insane.

Sharon didn’t like the confusion and anguish he saw on his soldiers’ faces. Like Dayan, he knew he had to challenge the story of Egyptian military supremacy. The best antidote to anguish was victory. And the best chance of victory lay in a counter-attack. Or so he thought.

But the first counter-attack in the Sinai was a disaster. The Chief of the Southern Command, Shmuel Gonen, gave conflicting, ever-shifting orders, failing to effectively coordinate the Israeli divisions.

His front-line commanders — Sharon in particular — were livid, convinced that Gonen had set them back significantly. Under Gonen’s command, the Egyptians overran several Israeli positions, destroying 50 tanks and killing or capturing dozens of soldiers.

By October 10th, it was clear that Gonen had to go. In his place, Golda Meir summoned Haim Bar Lev — yep, that Haim Bar-Lev — to repel the Egyptians back behind his eponymous line. It was under Bar-Lev’s command that Israel achieved its first significant victory on the southern front.

On October 12th, Israeli intelligence learned of an impending Egyptian attack on the Mitla Pass – a 20-mile long gully of sorts, sandwiched between two mountain ranges in the Sinai.

So when Egyptian commandos targeted an Israeli artillery battery in the wee hours of Sunday, October 14th, the Israelis were ready for them. They picked off 60 men before the Egyptians even knew what was happening. And when Egyptian armored brigades strayed too far from the shield provided by their surface-to-air missiles, the Israeli Air Force joined the fight. Within hours, Israel managed to repel the Egyptian attack, completely and irrevocably reversing Egypt’s momentum.

In response, Egyptian radio began fantasizing, crowing that Egyptian forces had taken the Mitla Pass. And in response, Bar-Lev informed Golda, quote, “We’ve returned to ourselves, and the Egyptians returned to themselves.” Sick burn, bro.

But perhaps the most notable victory on the southern front came between October 15th and 16th, when Ariel Sharon led the 143rd Armored Division across the Suez Canal. As one tank brigade distracted the Egyptians, another raced to protect the bridgehead over which the Israelis planned to cross. The battle was fierce.

But working together, tank and paratroop units ferried men and tanks across the canal on barges and rafts. By six AM on the 16th of October, three Israeli tank brigades had neutralized the SAM-missile sites on the western bank of the canal, clearing the skies for the Air Force. Israeli flags began to wave from Egyptian ramparts all along the canal.

In a status report to the Prime Minister on Wednesday, October 16, Moshe Dayan mentioned that he’d crossed the canal into Africa. He told Meir, quote, “There are a thousand soldiers there now. Tomorrow morning, the whole state of Israel will be there.”

The Egyptian Army had strict orders to remain in the Sinai. They weren’t going to give up territory again! Not after they’d made such a strong showing in the early days of the war. They put up a fierce fight as the Israelis crossed the canal, and the IDF lost hundreds of men and dozens of tanks.

Despite the cost, the IDF clinched its victory in the Sinai in a matter of days. By October 22, Israel’s 162nd and 252nd Armored Divisions had completely encircled the Egyptian Third Army. And Sadat, who had begun the war in a position of such strength, was forced to beg anyone who would listen to get the Israelis to agree to a ceasefire.

But that’s a story for the next episode, which just might be the most exciting one yet. Because wars aren’t fought solely on battlefields. They’re also fought in boardrooms and offices, in veiled threats and double-edged notes.

As the Israelis faced down two Arab armies, the US and USSR came perilously close to turning the entire world into their personal front line. The Cold War was turning hot. And when two global superpowers fight, everyone is in the line of fire. Join us next week for the epic conclusion to our three-part series.