What Happened?

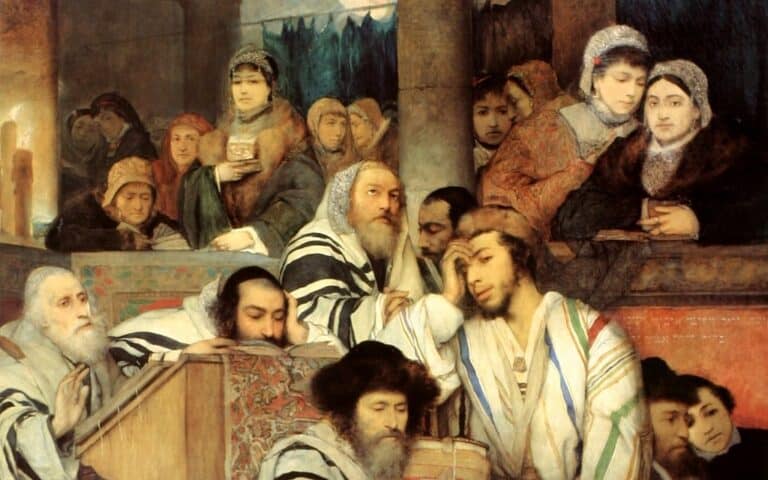

Jews in Israel and around the world are celebrating the “High Holidays” of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, which is marked by fasting and praying, is observed by some 73% of all Jewish Israelis. Eran Baruch, head of the Secular Yeshiva BINA, noted, “Yom Kippur is one of the most significant dates in the Jewish calendar. The Israeli street is paralyzed on this day and hardly any Israelis remain indifferent to this date.” The day is a unique one in Israel, as businesses close, public transportation stops and TV and radio programming turn off. People ride their bikes on virtually-car-free roads, including major highways. Israelis flock to synagogues, even if they do not usually attend services during the year. There is a stillness in the air.

Yom Kippur takes on added significance in Israel because of the Yom Kippur War in 1973, which Arabs often refer to as the October War or Ramadan War.

Yom Kippur War, 1973

On Yom Kippur in 1973, military couriers entered synagogues throughout Israel to announce that the country had been attacked by Egypt and Syria, and to call up reservists.

Before you go any further, watch our two-part series (part 1 and part 2) on the topic to get started.

- Holiest day interrupted – Jews around Israel were gathered in prayer on the holiest day of the year when the war broke out. Historian Abraham Rabinovich poignantly describes the feeling of the day: “Throughout the country, men wearing skullcaps and prayer shawls could be seen incongruously driving or trying to hitchhike to assembly points. Many men drove their wives and children to relatives before heading to their units. Resonant in the minds of all – those being called up and those left behind – was the ‘Unetaneh Tokef’ prayer with its poignant melody that they had chanted this morning about the prospects of the year ahead. ‘On Rosh Hashana it is written and on the day of the fast of Kippur it is sealed… who shall live and who shall die, who in his allotted time and who not, who by water and who by fire, who by the sword…’” (The Yom Kippur War, p. 99).

- Watershed moment – The Yom Kippur War was a watershed moment in Israeli history in several respects.

- It is the last war that Israel fought with a sovereign nation (subsequent ones, such as in Lebanon and operations in Gaza, were with specific terror groups).

- Second IDF Chief of Staff Yigal Yadin noted after the conflict, “This [was] the first war in which fathers and sons have been in action together. We never thought that would happen. We—the fathers—fought so that our sons would not have to go to war.”

- As Egyptian President Anwar Sadat started engaging in peace negotiations with Israel, most Arab commentators “assailed Sadat for selling us (Palestinians) down the river and then mocking us with empty promises of autonomy,” according to Palestinian academic Sari Nusseibeh. A wedge started developing between Egypt and the majority of the Pan-Arab world.

- Who won the war? Growing up, we typically heard that Israel clearly won this war. In reality, it was not that simple. Here is a helpful breakdown.

On the one hand: Historian Daniel Gordis notes that by the end of the war, “the IDF had performed admirably. In dogfights, the IAF shot down 277 Arab planes, losing only six of its own (a 46:1 ratio). Altogether, the Arab armies lost 432 planes to Israel’s 102….Arab casualties numbered 8,258 dead and 19,540 wounded, though some Israeli estimates of Arab casualties claim that the real losses were twice that—15,000 dead (among them 11,000 Egyptians) and 35,000 wounded (25,000 of them Egyptian).” Abraham Rabinovitch explains that Israeli soldiers showed their strength and were within miles of Cairo and Damascus. He argues that Israel’s ability to recuperate after the surprise was “epic.”

On the other hand: Gordis continues, “Israel lost 2,656 soldiers, with another 7,250 wounded. It was a figure dramatically lower than the Arab losses, but it was more than three times what Israel had lost in 1967—when it had tripled its size in a lightning war of six days. In this war, which had dragged on for much longer, Israel ended up essentially where it had started.” Both Gordis and Rabinovitch lament that this war shattered part of Israel’s soul. Palestinian academic Sari Nusseibeh has an interesting take, suggesting that Egypt “won by not losing” and showing that Israelis “were mortal after all.”

In conclusion: Rabinovitch concludes that “Egypt won and so did Israel.” Egypt ceased to feel the humiliation from 1967, and started the process of getting the Sinai back. From a political perspective, Egypt’s victory was “stunning.” Rabinovitch concludes that from a military standpoint, “the IDF’s performance in this war dwarfed that of the Six-Day War. Victory emerged from motivation that came from the deepest layers of the nation’s being.”

- Collective Cheshbon Hanefesh: Agranat Commission – It is well known that the Yom Kippur War caught Israel by surprise. Israel was in a post-Six-Day War euphoria and didn’t believe that her neighbors would act as aggressors again. Some, like Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, suggest that there was a “smug aura” of self-confidence in Israel after the Six-Day War. This was what Israelis called the “conception” or the “conceptzia,” the idea being that the neighboring Arab countries would never launch another war against Israel after the devastation it experienced six years prior. Daniel Gordis writes that there was “bravado and sense of invincibility,” as well as “unjustified sense of security.” Defense Minister at the time in 1973, Moshe Dayan, is quoted as saying, “I underestimated the enemy’s strength…and overestimated our forces and their ability to stand fast.”

After the Yom Kippur War, a special committee, the Agranat Commission, was organized by the Israel government to investigate the time period leading up to and during the war. The Agranat Commission ultimately found many errors within the military but largely avoided blaming government officials. Despite this, Prime Minister Golda Meir resigned from her post, and Defense Minister Moshe Dayan was not appointed to the next government. Regardless of blame and would-haves and should-haves, the Yom Kippur War left a deep scar in the Israeli psyche.

The Agranat Commission showed Israel’s deep loyalty to democracy. Civilians were holding their leaders accountable.

- Educational Lessons from the war – This article analyzes the war and the lessons we can learn from it. Why was Israel unprepared? What can we learn from it and apply to our own lives?

- Confirmation bias refers to the human tendency to seek, favor, or interpret information in a way that is compatible with one’s pre-existing beliefs. In 1973, Israel’s military intelligence leaders clung to interpretations of intelligence that validated their “conception” while dismissing alternative views.

- An overconfidence effect also played a role. The Blunder, as it came to be known in Israel, was not merely an intelligence failure, but also a failure of preparation. The Israelis were wildly outnumbered in both the Sinai and the Golan, and not entirely for lack of resources. Rather, Israel’s stunning victories against Arab forces in 1948, 1956, and 1967 had produced among its leaders an impression of Israeli military superiority and of Arabs as poor fighters. Chief of Staff David Elazar summed up this dynamic when he told his staff, “We’ll have one hundred tanks against [Syria’s] eight hundred. That ought to be enough.”

- A peak-end effect. Israeli nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman notes: “Our memory has evolved to represent the most intense moment of an episode of pain or pleasure (the peak) and the feelings when the episode was at its end.” IDF leaders’ recollection of past Arab-Israeli wars came to be dominated by memories of dramatic operational successes and victorious end-states, yet the Israeli military possessed plenty of data that belied this confidence.

Yom Kippur, Today

As mentioned above, Yom Kippur is a unique day on the Israeli calendar. It is a day marked by 73% of the Israeli Jewish population, including 46.5% of secular Jews. What does religious observance look like in Israel today?

- Increased religious observance – Studies show that religious observance in Israel is on the rise. In 1999, 16% of the population identified as Haredi or Orthodox, and the number rose to 22% in 2009. In those same years, the number of people who reported that they observe religious tradition “to a great extent” rose from 19% to 26%. And a smaller percentage of people identified as secular, falling from 52% to 46%. See a full analysis for some fascinating numbers and deductions.

- Why observe Yom Kippur? Surveys show that 73% of Jewish Israelis observe Yom Kippur. Their reasons for celebration are diverse and quite interesting. Of those who report fasting, 51.5% do so for religious reasons, 22.5% do so out of respect for Jewish tradition, while 14% do so in solidarity with the Jewish people. (A fraction, 3%, fast for health reasons or as a challenge, and 9% chose all answers equally or none at all.)

- Religion and State – Eran Baruch, head of the Secular Yeshiva BINA, makes the following point about religious observance in Israel: “Fasting on Yom Kippur is voluntary. No one forces us to fast. And precisely in such a place where each person can do as he pleases, many do take part in it. This shows that when there is less religious coercion bigger parts of the public choose to identify and participate.” Indeed, voluntary religious practices in Israel, such as Yom Kippur and Pesach Seder, are widely observed, whereas State-mandated practices, such as Orthodox weddings and hametz restrictions, are often resented and circumvented.

- The “Four Tribes” – In 2015, President Reuven Rivlin delivered a now-famous and powerful speech about the “four tribes” of Israel: Haredi, secular, national religious, and Arab. He addressed the growing diversity and lack of interaction between the different “tribes.” He stated: “We must not allow the ‘new Israeli order’ to cajole us into sectarianism and separation. We must not give up on the concept of ‘Israeliness’; we should rather open up its gates and expand its language.”

Originally Published Oct 7, 2019 11:15AM EDT