Who should serve in the Israeli military?

It doesn’t sound like a particularly spicy question, does it? Because the obvious answer is… “Israelis.” Case closed, next question.

But lean in a little closer, and you’ll understand why this question is at the heart of Israel’s most fraught culture war. Remember, Israel is tiny, with a population roughly equivalent to that of New York City. But unlike New York City, Israel borders three enemy territories: Lebanon, Syria, and Gaza. Plus, you know, 26 countries that refuse to recognize the world’s only Jewish state. Like Iran.

A small country with big enemies has to rely on its military prowess. After all, the state was established as a safe haven for the world’s Jews.

But… 20% of Israel isn’t Jewish. Should Christian, Muslim, Baha’i, and Druze citizens be conscripted into a Jewish army? What if they have relatives in the West Bank and Gaza, who they might be forced to fight against in a war?

See? It’s a can of worms.

You might think things would be a little simpler when you look at Israel’s Jewish population. Jewish army, Jewish citizens… OK. So all of Israel’s Jews should serve. Right?

Well… it’s complicated. Because as of 2019, only 69% of Jewish men and 56% of Jewish women are drafted into the IDF.

Some earn exemptions because their physical and mental health doesn’t allow them to serve. Some choose instead to do a year of service to the state. A tiny number are pacifists who refuse the draft on moral grounds.

But there’s only one group of Jewish Israelis who enjoy a near-total exemption. Who in 2019 sent only 1,222 men, and 0 women into the IDF – a miniscule fraction of their numbers. Whose status in society is becoming an increasingly sharp thorn in the side of many other Israelis.

Who is this group?

Why would Israel’s first PM, David Ben Gurion, agree to a blanket lifetime exemption for a single group of Jews? And if the Israel-Palestinian conflict is ever solved, will Israel’s next major conflict be between its Jews?

A house divided

So, first, some basic demographics. Israel is home to 9 million people – 80% of whom are Jews. Among those Jews are the Haredim – aka the ultra-Orthodox, who make up 13% of Israel’s population. That’s about 1,226,000 people.

“Ultra-Orthodox” isn’t the nicest label, with its connotations of fringiness or extremism. So we’re gonna stick to the much more inclusive term haredi. The word literally means “one who trembles.” As in, trembling before God. As in, Isaiah 66:2, where God says he seeks the kind of person חָרֵ֖ד עַל־דְּבָרִֽי – who will tremble at My word. (Nerd corner alert: Haredi shares its root with “charada,” the modern Hebrew word for “panic.”)

But being Haredi has nothing to do with panic. Instead, the Haredi world revolves around Torah, and of course, its divine author, God. Haredi lives, like the lives of other observant Jews, are governed by a strict adherence to halacha, or Jewish law.

Now, I know that someone is going to ask “wait, is Haredi the same as Hasidic?” Good question, but no. Without going into too much detail, I’ll just sum it up like this: all Hasidic Jews are haredi, but not all haredim are Hasidic. You know, kinda like all squares are parallelograms, but not all parallelograms are squares.

Haredi is an umbrella term that describes a vibrant and highly diverse group. That’s really important for us to emphasize. Because where secular Israelis might see Haredim as a solid wall of black and white, a uniform rejection and refusal to integrate, that’s an incredibly unfair view. Like every other community on the planet, the Haredi community is textured.

Still, some basic facts unite all Haredi Jews. The controversial “ultra” in the moniker ultra-Orthodox comes from the general Haredi rejection of secular life. Or, as scholar Aharon Rose puts it: “Haredi Judaism, regardless of its particular faction, objects to Jews entering the cultural fray of the modern West, studying in its institutions, revering its leaders, fighting in its wars, or partaking of its cultural bounty.”

But even that is controversial. Because modernity is hard to resist. So let’s put it like this: Haredim might use the Internet. They might play or watch sports now and again. They might go to college. But many Haredim DON’T do these things. It’s perfectly normal for a Haredi Jew to stay off the Internet or spend their whole life learning Torah. And it’s perfectly normal to stay permanently ensconced inside a Haredi bubble.

Here’s Nechemia and Yehudit, a Haredi couple from Jerusalem, describing their lifestyle:

“We’ve never met non-religious Jews. You know, occasionally you walk in the street, you go to buy something, you go to the mall, you see them, but you have nothing to do with them. They’re like, out there. There’s like a big wall separating between you. It’s not a physical wall. But you basically have nothing to do with them.”

In fact, this so-called “wall” between Haredi and non-Haredi Jews was dramatized in a dystopian Israeli TV show called “Autonomies”, which imagined a world in there are two Israels: the secular country, with its capital in Tel Aviv, and the Haredi one, centered in Jerusalem. As might be obvious from the premise, this isn’t a peaceful split.

You can learn a lot about a culture’s fixations and fears from its fiction. And this show demonstrates that non-Haredi Israelis are extremely troubled by the invisible wall that separates Haredim from the rest of Israel’s Jews.

Nowhere is this wall more apparent than in the IDF conscription office. As of 2016, a whopping 88% of Haredim are younger than 25 years old. That’s a lot of 18-24-year-olds. Yet in 2019, only 1,222 Haredi men chose to enter the military. That’s less than 1% of the total Haredi population. And despite countless efforts to raise that number, many Haredim are resistant to the prospect of conscription.

Here’s an unnamed Haredi protestor speaking to French TV in 2017, furious at the prospect of a mandatory draft for his community:

“Israeli country is the one democratic country in the world where they take people in the army like the Communists. I don’t want go. What they want from me? I don’t take them to be like me.”

Why don’t most Haredim join the Israeli army?

Like so much about Israel, the answer to that question is rooted in history that predates the state. So… let’s talk about the forces, both internal and external, that have shaped the Haredi community. Because I’ve been throwing a lot of statistics at you. But statistics are only a small part of the story.

As pogroms swept through Europe in the early 20th century, displacing millions of Eastern European Jews, traditional communities found themselves transplanting their customs in the friendlier ground of Palestine or America. And as the Nazi machine mowed relentlessly through Europe, the continent’s remaining Haredi communities were all but devastated.

Even in 2022, the Haredi community feels that loss. Their Sages and traditions and villages – all cast into the flames. So as survivors made their shell-shocked way to safety after the war, the Haredi community redoubled its commitment to protecting its ravaged identity.

It wasn’t easy. Many Haredi survivors made their way to Israel – a country founded on the premise of The New Jew. And there, they found their identities challenged as they confronted Zionism’s total rejection of the traditional European Jewish identity.

Or, as Oz Almog puts it in his book The Sabra: The Creation of the New Jew:

“The Zionist revolution is generally presented as a revolution against the traditional Jewish world….a process summed up as ‘the rejection of the Diaspora.’”

Of course, this is pretty simplistic, and Almog continues to say that “Zionism’s relation to tradition was a complex and convoluted combination of rejection and acceptance.”

But as you might imagine, the Haredi world was not interested in “a convoluted combination of rejection and acceptance” of their identity. Zionism was simply not compatible with their way of life.

Not to mention that many viewed Zionism as out-and-out heresy. And why wouldn’t they? Early Zionist thinkers, like Micha Yosef Berditchevsky, literally said, “Ivrim anachnu vi’et libeinu na’avod.” We are Hebrews, and we’ll serve ourselves (or our hearts).” Not, We are Yehudim, we are Jews. But we are Ivrim, we are Hebrews. The language is intentional. It severs the Jewish community from its past – a past that so many early Zionists found shameful. A past that the Haredi community cherished.

To explain the general – though not monolithic – Haredi view on Zionism would take an entire podcast in and of itself. But in short, like most Jews through the 2,000-year-exile, Haredim prayed towards Jerusalem and dreamed of Zion, and the redemption of the Jewish people that would return them to their land. But their Zion could not be constructed by a bunch of atheists in shorts. Their Zion was Messianic. Only God could redeem the Jewish people. The Zion of a Jewish theocratic monarchy, a Third Temple, and a Messiah.

So the Haredi community disengaged. As Zionists built new cities all over the growing country, Haredim built their own cities, enclaves in Jerusalem and Bnei Brak where they could raise families, study Torah, and recreate – as best they could – the vanished world of prewar Europe.

And… it worked. Scholar Aharon Rose observes:

“Six decades after the death camps… the Haredi, or ultra-Orthodox, community—the last vestige of prewar traditional Jewish society—is experiencing a revival of incomparable scope. With one of the highest birth rates in the Western world, Haredi communities both in Israel and abroad boast numbers in the hundreds of thousands, and enrollment in Haredi yeshivot, or centers of learning, is at higher levels than ever.”

In other words: that Haredi commitment to Torah values and a Torah lifestyle? It’s successful because the Haredi community protects itself fiercely from the rest of Israeli society.

But if there is one factor that unites all Jewish Israelis and shapes the Israeli identity, it’s the military. And to truly understand the Haredi resistance to the IDF, you need to understand the place it occupies in Israeli society. Because no Israeli institution represents Israeli society quite like the IDF.

The great equalizer

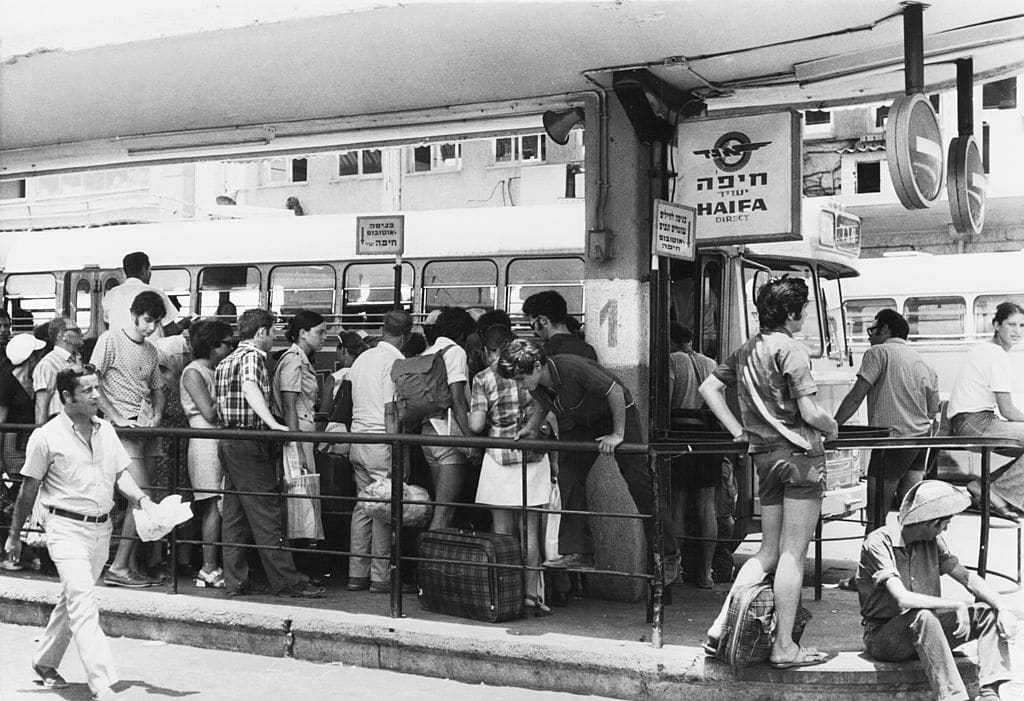

The Israeli army is the great equalizer. The crucible where an Israeli identity is forged, where people from all backgrounds and cultures rub elbows. Form bonds. Work together. Fall in love. Even meet their future spouses. (Nerd corner: the IDF website ran a cute series of articles about couples who met during their military service, including Minister of Defense Benny Gantz and his wife Revital.)

But none of those are values the Haredi world is looking to adopt. They have their own systems that teach teamwork and responsibility. Their own institutions that allow young people to meet and create families. Their own way of defending the state, which we’ll talk about in a second.

So to them, the IDF doesn’t occupy quite the same hallowed ground as it does for other Israelis. Which, as you might imagine, can be a sore point for the rest of Israeli society. Not to mention the Israeli government.

So… how did we get here? The IDF has been an institution since before the creation of the state. (As I say constantly, listen to our Black Saturday episode for more on that!) So the Haredi community didn’t just wake up one day in 1999 and decide “nah, no army for me.”

So what happened? How did the Haredi community manage to wrangle an army exemption for their community?

A deal to not serve

Let’s do a thought experiment. I want you to put yourself into Ben Gurion’s shoes for a second. It’s 1947. 66% of European Jewry has been wiped out. A stream of refugees is making its way towards the Promised Land, reuniting with the deeply religious Jewish community who had lived there for hundreds of years.

And your #1 job is getting the state for the Jews over the finish line. It’s what you’ve been pouring your entire self into for years, and it’s so, so close, you can taste it. The British are peacing out, the UN is almost on board! But…it’s not quite a done deal yet. As the British prepared to hand Palestine over to the Jews and the Arabs, the U.N. established a “Special Committee on Palestine,” or UNSCOP, whose report would decide the fate of the yet-unborn state of Israel. UNSCOP’s job was to meet with Jews and Arabs alike to better understand each group’s vision for its future independent homeland.

Along with Ben Gurion and other Zionist groups, UNSCOP also planned to meet with the Haredi political party Agudat Yisrael, which is now a major force in Israeli politics. But remember: Haredim and secular Zionism… well, they’re not the best of friends. So back in ‘47, the Haredi bloc represented a significant threat to Ben Gurion’s vision of an independent Jewish state. Because if Agudat Yisrael told UNSCOP that they were perfectly happy without a state… well, that would be bad.

Because the Haredi community had been in Israel – then called Palestine – for a long time. Their voices mattered. And their voices could be disastrous to the whole Zionist project.

Itzik Ackerman, a young Haredi father and full-time yeshiva student, expresses the party’s original ethos vis-a-vis the Zionist movement. His words illustrate why Ben Gurion took the Haredi bloc SERIOUSLY:

“We lived here just fine without you Zionists for 800 years. Suddenly, you showed up. Your first Aliyah was in 1882. First Aliyah. Yeah right, First Aliyah. You showed up out of nowhere! We [the Haredim] are the first Aliyah. Then you show up in the 1800s and establish a state? Where did you even come from? You can leave, we lived here just fine without you. Oh, we’re starting a state, and it’s gonna be secular, and we’ll do whatever we want, we’ll have the Eurovision contest on Shabbat… Like, guys? Give us a break. You can go. We lived here just great without you.”

Imagine if Agudat Yisrael had said all that to UNSCOP back in 1947.

So Ben Gurion did what all smart politicians do. He made them an offer they couldn’t refuse. If they agreed to support the Zionist state, he’d make sure that Israel retained its Jewish character.

What does that look like, practically, you ask? Well, a few things.

Number one: he agreed that Shabbat and holidays would be a part of the national calendar. Sounds great, right? I love going to Israel and feeling the peace of Shabbat settle over me as the traffic dies down and the buses in Jerusalem stop running. But I can see how this might rankle if you’re not observant.

Number two. Ben Gurion granted the Haredim control over all Jewish marriages and divorces. Now, my wedding was uber Orthodox (and uber fun…by the way, Orthodox Jewish weddings are a blast. I’m not saying you should have Orthodox friends just to be invited to their weddings… but I’m not not saying that.)

Still, not everyone wants an Orthodox wedding. True, most Jewish Israelis are pretty accustomed to the status quo. But a number are trying to change Israel’s marriage system to be more inclusive. Because only Orthodox ceremonies are legally binding in Israel. You want a Conservative, Reform, Reconstructionist, Renewal, interfaith, or same-sex Jewish wedding? Head over to Cyprus. Of course, this is also an episode in and of itself.

Number three. Ben Gurion also gave Haredim control over kashrut certifications. Which meant that only they could decide whether a restaurant or grocery store was kosher. Non-Haredi definitions of kashrut were not considered valid.

And number four, Ben Gurion agreed to military exemptions for yeshiva students. So when most other Israeli 18-year-olds were graduating from high school and shipping off to basic training, their Haredi counterparts were going straight to yeshiva, to continue their Torah learning.

Sounds like Agudat Yisrael got quite a deal, no? So why the heck would Ben Gurion agree to all this? Though he was raised in an Orthodox home, Israel’s first PM stopped practicing Judaism when he moved to Palestine. He didn’t keep Shabbat. His son married a non-Jewish woman – a woman who Ben Gurion absolutely loved, by the way – meaning that his marriage wasn’t recognized by the Israeli rabbinate. Most importantly, as the soon-to-be head of a tiny country surrounded by enemies, why would Ben Gurion exempt yeshiva students from the draft? Especially in the face of an inevitable Arab invasion?

But remember, hindsight is 20/20, and this was back in 1947. The danger of Agudat Yisrael getting in the way of the Zionist project was real, and at the time, there were only four hundred Haredi yeshiva students in the entire country. And meanwhile, huge numbers of non-Haredi Jews were flocking to Israel from all corners of the earth. So the first PM was convinced that – like so much else from the Diaspora – Haredi religious traditions would simply… fade away in the face of the New Judaism.

Plus, Ben Gurion wasn’t exactly opposed to Bible study. True, he may have been an atheist. He may have believed that the “New Jew” should work the land, serve in the army, be a part of the Zionist cause. But his diaries and conversation were absolutely peppered with Jewish aphorisms – quotes from Tanakh, bits of Jewish wisdom, lessons he had learned from wise scholars. To him, the Tanakh was one of Judaism’s most valuable cultural legacies. Perhaps most of all, he loved Judaism. He loved Jews. He wrote once: “I won’t label a Jew as either religious or secular – but only a Jew. There were always disagreements and quarrels among Jews in every generation, from ancient times to the present. There is nothing catastrophic in this. The catastrophe occurs when one side ceases to respect the other and begins hating it.”

And as the founder of a fragile, fractious state, Ben Gurion was more than happy to let future generations figure out this whole religion thing. He was just trying to ensure that his tiny state survived. He didn’t have time for these squabbles.

As for Agudat Yisrael, they held up their end of the bargain. Their testimony to UNSCOP runs a whopping 58 pages. But it affirms, and I quote: “We are establishing the Jewish national home… Over the whole country the one national flag of the Torah is to be flying, just as over all the country there is only one flag of Zionism flying. That can be done only by one national territorial community of the Torah.”

In other words, from their perspective, the Jewish state was a go.

A new status quo

Without quite realizing it, when he made this deal with the Haredim 75 years ago, Ben Gurion had set the status quo. Seriously. That’s what we call the deal today: the status quo agreement. And, as Haredi leading public intellectual and rabbi Yehoshua Pfeffer says: “Once you have a status quo, then it becomes sanctified somehow, and obviously, it’s become very much entrenched in political Israel.”

But the status quo was starting to chafe a little by 1952. Ben Gurion was having some second thoughts about this deal to exempt yeshiva students from the army – and about the growing divisions between Haredi and non-Haredi Jews. One percent of the country was killed in the War of Independence. One percent. Almost every family had lost someone. It had to hurt most Israelis that the military burden wasn’t shared equally.

So this most secular of politicians approached the most illustrious of rabbis: Haredi luminary Rabbi Avraham Yeshaya Karelitz, better known as the Chazon Ish.

And the Chazon Ish, who knew that Ben Gurion was looking for some advice, came prepared. He invoked the Talmudic parable of two camels walking down a road. One camel is laden with goods, nearly buckling under the weight. The other is unburdened.

The Chazon Ish asked Ben Gurion, “Which camel should make way for the other?” And just in case Ben Gurion missed his point, he clarified: the camel with the backpack? That’s the Haredim, bent under the yoke of Heaven. The unburdened camel? That’s everyone else, free of the spiritual concerns that dominated Haredi life.

The implication was clear, at least to the Chazon Ish. The camel with the backpack, the Haredim, they’re exhausted. They’re carrying the burden of the whole country! Of course the other camel, free, no care in the world, should step aside for the other.

As you might imagine, Ben Gurion did not appreciate this depiction of Israeli society. Sure, Haredim have the heavy yoke of the Torah and the commandments. But non-Haredi Jews carry the burden of defending the country. Absorbing its immigrants. Running its economy. How could Haredi Jews not see that?

Well, very easily. Because – as the Chazon Ish explained – Haredi Jews provided a massive, though invisible, spiritual service to the state. To the entire Jewish people!

Or, as Itzik Ackerman put it in a 2021 documentary about the Haredi world, “Do you know what would happen if I didn’t sit here and learn Torah? I am helping create the world. I am the engine. I stop the Torah study and it’s like the battery is pulled out from the world. Go tell that to the average secular Israeli, and he’ll look at you like… ‘bro, go to the psych ward ASAP.’”

This belief in the invisible protection of Torah study animates Haredi discourse. To take a Haredi Jew from his Torah study is to puncture, even if just a little, the invisible shield that the Haredim hold over the entire state. This is what Rabbi Yehoshua Pfeffer calls the “Torah Dome.” It’s a play on the Iron Dome defense system that protects Israelis from frequent missile attacks. Most Israelis probably don’t understand the science and engineering behind the Iron Dome. But they believe that it works. Similarly, Haredim believe that the Torah is equally protective, even if most secular Israelis can’t – or refuse – to understand this.

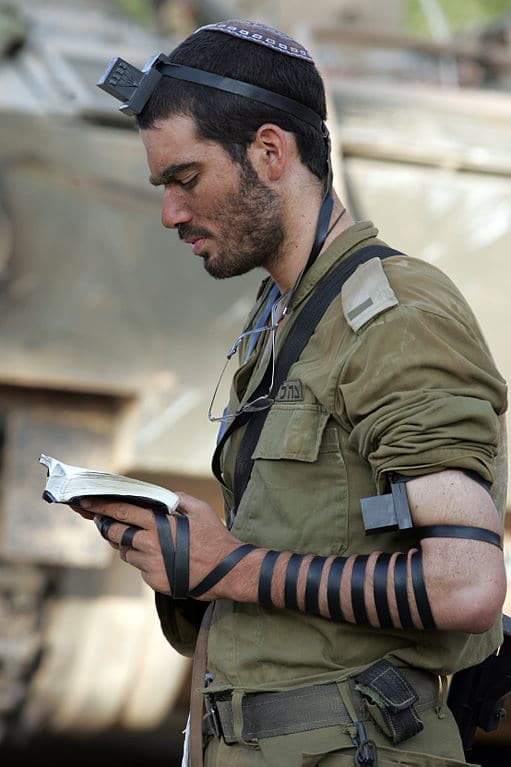

Even Haredi soldiers agree:

“Everyone has a purpose. We as devout Jews believe that some people’s purpose is to study full-time. And that’s a really important purpose…. We’re defending Israel physically. But I really believe that full-time Torah scholars protect us much more deeply on a spiritual level.”

Haredi soldiers?

Remember when I told you about the 1,222 Haredi men who entered the army in 2019? They were followed by additional soldiers in 2020. In 2021… though no official stats are available yet. Sure, it’s a small number. Still, it’s not nothing. I told you the Haredi world was complicated.

I’ve just spent the past twenty minutes telling you that Haredim don’t join the army. That it’s a threat to their identities. That they’re busy engaged in the spiritually important work of building the “Torah Dome” around the state of Israel. That many are non-Zionist and have little interest in rubbing elbows with their non-religious and even non-Jewish fellow citizens.

And all of that is true.

But at the start of the episode, we mentioned that roughly 1% of the Haredi population chooses its own path. Roughly 1% – all male – chooses to enlist. And their reasons for doing so are varied.

Most are united, though, by the benefits that the army provides.

See, Israel’s Haredi population tends to be quite poor– 44% of the Haredi community lives under the poverty line. The men generally learn in kollel, or yeshiva, full-time, leaving the women as the primary breadwinners. And since Haredim usually have large families, with seven children on average, the paychecks stretch thinner and thinner with each child. Eventually, many Haredi men do end up needing to work, at least part-time, to supplement their wives’ incomes.

But to succeed in the job market, you need basic skills. Like English. Or math. Subjects that the Haredi school system sometimes doesn’t teach. Because nearly one quarter of all Haredi schools are exempt from the standards and requirements of the Israeli Ministry of Education. So while some Haredi schools equip their students with the skills necessary to succeed in a competitive job market, many do not. And if they want to pull their families out of poverty, Haredi men and women increasingly need a basic high school education.

Without an education, Haredim in the workforce are limited in their ability to find a well-paying job, or even any job. But the army gives Haredi men a leg up, even paying for their secular studies. A retroactive diploma enables these young recruits to command higher salaries when they enter the job market. Some will even go on to higher education. Between 2010 and 2020, the number of Haredi students pursuing higher education has tripled. As of 2021, there are roughly 14,700 Haredi students – of both genders – pursuing a degree in fields like education, business administration, or paramedical roles like nursing, physical therapy, and emergency first aid.

But money and education aren’t the only benefits to joining the army.

On the whole, Haredi Jews may not be Zionists. They may reject secular life. But they can’t deny that there’s a warmth to belonging to a wider cause. And as recruits in a Haredi-only unit, they don’t need to worry as much about interacting with secular Israelis.

Many recruits feel a sense of pride, of ambassadorship. Here we are, they say. Living proof that Haredim are able and willing to contribute to wider Israeli society.

“It wasn’t the motivation for joining the army,” they say. And yet, it’s a side benefit. A benefit that frightens many Haredi parents. True, all parents want their children to succeed. But most don’t want that success to come at the expense of their child’s identity. Of the lessons that they’ve tried so hard to inculcate from day one. You and I might think it’s wonderful to hear these young recruits talking about their sense of belonging, but what do their parents feel? What about their communities?

Well… most don’t approve. And their children have internalized that attitude. Here’s Avshi Akerman, the oldest of Itzik Ackerman’s five children.

A reporter asks: “What do you want to be when you grow up?” Avshi answers: “You can’t think about that. Everyone in my class says something different. I’ll be a full-time Torah scholar. I’ll be the head of a yeshiva. I’ll be… whatever, everyone says something different.” The reporter asks another question: “Are you leaning more towards being a full-time Torah scholar? Or more towards being a soldier?” Avshi laughs, it’s such a ridiculous question. “I won’t be a soldier, that’s for sure.”

Representation matters. Avshi wants to be what he can see. And he sees full-time scholars. He sees heads of yeshivas. He doesn’t see soldiers. Not in his community. And that’s not an accident. The Haredi community has staged countless protests against any attempt to woo their young men into the army. The clashes are hard to watch. I don’t like seeing mostly-Jewish policemen scrapping with fellow Jews.

And… here I go, getting provocative again… but I understand where haredim are coming from. The wildly popular Israeli show Shababnikim centers on a bunch of Haredi yeshiva students. But they’re not the serious scholars you might expect – in fact, the Israeli slang word “shababnik” means, roughly, “a Haredi youth who spends most of his time goofing off.” But though these kids are more or less endearing bozos, they remain committed to their Haredi identities. In one episode, a yeshiva scholar asks a secular soldier: “If there were a completely Haredi army, and you knew that if your child served in it he would likely become Haredi, would you let him go?” I like it.

It’s a question that many secular Israelis likely haven’t considered. To them, the army is a fact of life. A major component of Israeli identity. They may wonder what if my kid comes back wounded, or what if my kid comes back with PTSD. But they probably don’t wonder what if my kid comes back with an identity I don’t recognize and can’t relate to? An identity I have spent years trying to avoid?

But as an Orthodox Jew, raising Orthodox children, that’s a question that keeps me up at night. I live in the Diaspora. I’d be lying if I said that I didn’t worry about the prospect of secular college, of big cities with negligible Jewish presence, of alternate ways of living life. That tightrope isn’t an easy place to balance. Yes, I’ve chosen to walk it. But I get why the Haredi community has decided to eschew it all together.

But many non-Haredi Israelis see the issue as black and white – pun intended. To them, Haredim are citizens. And all Jewish citizens have an obligation to the state. As of 2018, 70% of Jewish non-Haredi Israelis believe that Haredim should enlist. They live in Israel, the thinking goes. They should contribute. Like the rest of them do.

An informal 2012 street poll bears this out. Corey Gil-Shuster, of the “Ask an Israeli/Ask a Palestinian Project,” asked non-Haredi Israelis whether they believed Haredim should serve in the army. The answer was a resounding yes.

Still, non-Haredi Israelis admit that Haredim can contribute in other ways. For example, in 2019, roughly 14,000 Israelis chose to do a “shnat sherut,” or a year of national service. But in 2020, only 495 Haredim took this option.

Time and again, the Israeli government has tried to find ways to bridge the gap between Israel’s Jewish groups. The government has established a number of commissions to research solutions for the gap between Haredim and other Jews. Still, the vast majority of Haredi boys do not enter the military. And any attempt to conscript them is met with fierce protest.

What does this mean for the IDF, the so-called “People’s Army”? Can it still be a People’s Army without a significant percentage of its people?

No one truly knows the answer to this question. But – as we said earlier in this episode – you can learn a lot about a society from its fiction. A number of recent Israeli TV shows have begun depicting the Haredi world with empathy and curiosity, rather than disdain. You may have heard of Shtisel, which treats its slightly dysfunctional multigenerational clan with warmth and sympathy. But Shtisel doesn’t delve too deeply into the question of conscription.

Kipat Barzel, or “Iron Dome,” centers on an all-Haredi unit dealing with the ups and downs of military life – including the disapproval and anger that so many Haredi recruits face at home. And I’d argue that aside from being entertaining, these depictions are incredibly important. Humanizing. Because even if a Haredi boy wants to serve in the army, lured by its many incentives, there’s no guarantee that his community will let him. And that is a challenge that many non-Haredi Israelis – for whom the army is a fact of life – seem not to understand.

Five Fast Facts

So… that’s a quick look at the very complicated story of Haredim and the army, and here are your five fast facts.

- The state of Israel imposes a mandatory draft on all Jewish citizens. But Haredim, or ultra-Orthodox Jews, are exempt from army service. Which, as you might imagine, is a sore point for most non-Haredis.

- The exemption was codified by an unlikely figure: the diehard secularist David Ben-Gurion. Israel’s first PM believed in the cultural and national importance of Torah study. But Ben Gurion feared that the Haredim might tell UN observers that they didn’t feel they needed a state. So he cut a deal with the Haredim with all sorts of incentives – including the draft exemption.

- At the time, the exemption only applied to 400 people. But Haredi Jews tend to have very large families. Today, over 60,000 Haredi Jews are exempt, and the number will likely grow due to the community’s high birth rate.

- There have been numerous attempts to make army service a more palatable prospect for Haredi Jews, including financial incentives. And these days, a tiny minority of Haredi Jews do serve in special units sensitive to their religious needs.

- Haredim who enlist are in the minority. Simply put, the Haredi community believes that Torah study and other spiritual contributions are as important to national security and identity as military service. They feel themselves called to serve someone far more important and authoritative than the state – God. And in that service, they find their purpose among the people of Israel.

Those are your five fast facts, but here’s one enduring lesson as I see it. Though I’m a passionate Jew and Zionist, I’m not an Israeli. I didn’t serve in the IDF. I don’t need to confront the electrifying and terrifying thought of my children protecting the Jewish state with their own bodies. My cousins do, my uncles and aunts did, and who knows? Maybe my children will want to enlist in the Israeli army. For them though, it will be a choice.

So I’m a bit hesitant going down the potentially judgemental rabbit hole of asking whether I believe all Haredim should serve. I didn’t. So I probably shouldn’t be making sweeping moral pronouncements. (Though really, what else is the point of a podcast?)

Especially because to be honest with you, I think the Haredi community makes an important point. Yeah, Israel’s national security – not to mention its internal character – is paramount. But as an *aspiring* religious Jew, I also think there’s something sort of crucial about the spiritual role that Haredim often fill in Israeli society.

So non-Haredim MUST work to understand where Haredim are coming from before the IDF can truly become integrated. And Haredim have to understand the pain and resentment of a mother who has lost her son in the latest clash… while Haredi boys are safely learning in yeshiva. Because someone has to physically defend the Jewish state. And in this tiny, blood-soaked corner of the world, every Israeli owes his or her life to the IDF.

But the two sides are so mired in resentment that they talk past each other. And it’s this conflict – Jew vs. Jew in the Jewish state – that keeps me up at night. Sure, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict provides plenty of fodder for my chronic anxiety. But I firmly believe that Jewish history is up to us – the Jews.

It’s the way we Jews treat each other – NOT the way that non-Jews treat us – that will determine what our world looks like. Will we build a peaceful world? A utopia of mutual respect? Or will we tear each other down? Will we hurl insults, ignore each other’s pain, and look past one another?

We know what happens when Jews are divided. That’s how you get 2,000 years of exile.

And I don’t think I’m being dramatic when I say that the success of the Zionist project – of the Jewish experiment of modern self-determination – depends on Jews bridging their gaps. There’s little point to kibbutz galuyot – the ingathering of exiles – if a significant percentage of said exiles seem determined to misunderstand each other.

Like the Israeli army, I believe that no one should be left behind. So whatever integration looks like, it cannot be done by force. Israeli society will not be sustainable if the gap between Haredim and non-Haredim continues to widen. Each side needs to view the other with respect. With a keen understanding of the other’s legitimacy. With gentleness.

It’s not gonna be easy. It certainly wasn’t for our ancestors! But it’s a challenge that Israel must rise to meet. Because Haredim will make up an enormous sector of society within a few decades. If Israel doesn’t find a way to include them – in the army, in the workforce, at the polls – then the country faces a great danger. We know what happens to divided societies. And we didn’t endure exile for 2,000 years just to tear each other apart.

So… that’s our provocative episode. And now it’s your turn. For the first time ever, we’re ending with a poll. What do you think? Should all Jewish citizens, who are physically and mentally fit, serve in the Israeli army?

Check out the poll at jewishunpacked.com/israeliarmy.