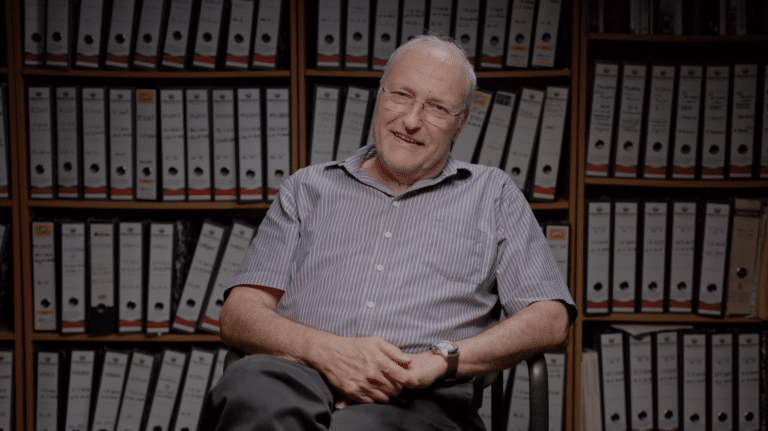

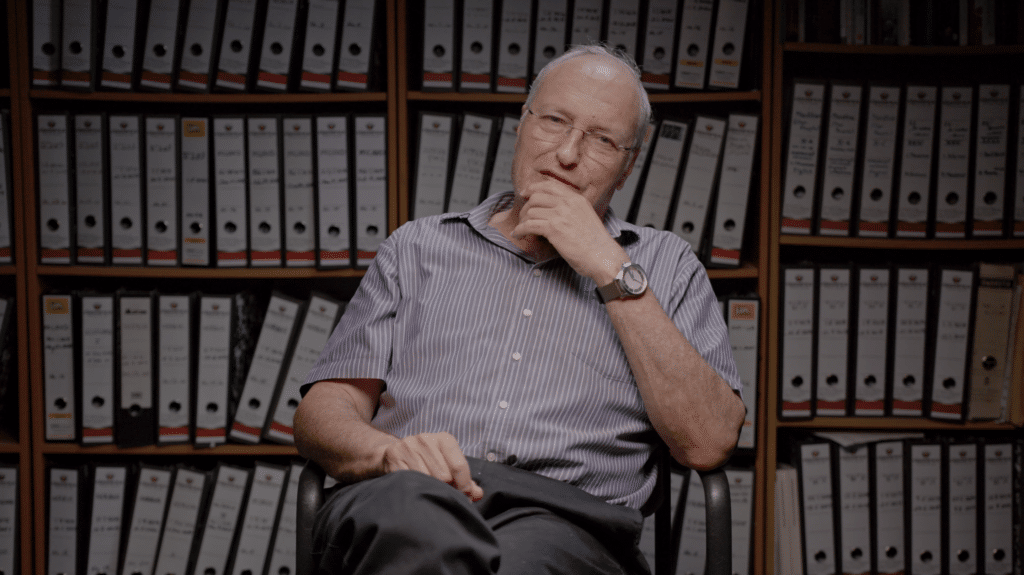

Efraim Zuroff doesn’t run away from Nazis. Instead, he finds them.

“What do I do for fun?,” he laughs, before joking:

“I torture Nazis.”

Zuroff has visited more places than most — but not for tourism. He goes to the hidden corners of the world where people don’t want to be found.

His mission: tracking down Nazis and bringing them to justice.

“I’m a Nazi hunter,” he told me when we sat down for an interview in Jerusalem.

“When people ask me: ‘what’s your job?’ I say: one-third detective, one-third historian and one-third political lobbyist.”

Zuroff’s latest efforts have been focused on two German trials which both took place this past month.

First, the trial of 100-year-old ‘Josef S’ who is on trial for complicity in the murder of 3,518 prisoners at the Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp, where he worked as a guard. ‘Josef S,’ who was identified this way in keeping with German privacy laws, is the oldest defendant to ever stand trial in Germany.

Second, the trial of 96-year-old former Nazi secretary, Irmgard Furchner, who started working at Stutthof Concentration Camp at 18 years-old and is charged for helping murder more than 11,400 people.

Zuroff’s role includes tracking down escaped Nazi war criminals like the ones currently on trial today, gathering evidence to prove their complicity in the Holocaust, and lobbying those in positions to serve justice.

As the last remaining Nazi hunter of his kind, Zuroff is committed to the task as ever. At 72, he’s dedicated his entire career to this pursuit.

“I’ve been everywhere trying to track these people down, trying to build cases against them and trying to convince countries to put these people on trial and bring them to justice.”

Zuroff was born three years after the end of World War II in New York City and cites his parents as the inspiration for his work.

After completing his undergraduate degree in history at Yeshiva University, he moved to Israel and got his masters and later a PhD in Holocaust studies at Hebrew University.

In 1986 he became director of the Jerusalem office of the Simon Wiesenthal Center; and since then, has submitted the names of more than 3,000 Nazi war criminals who escaped post-war to countries all over the world.

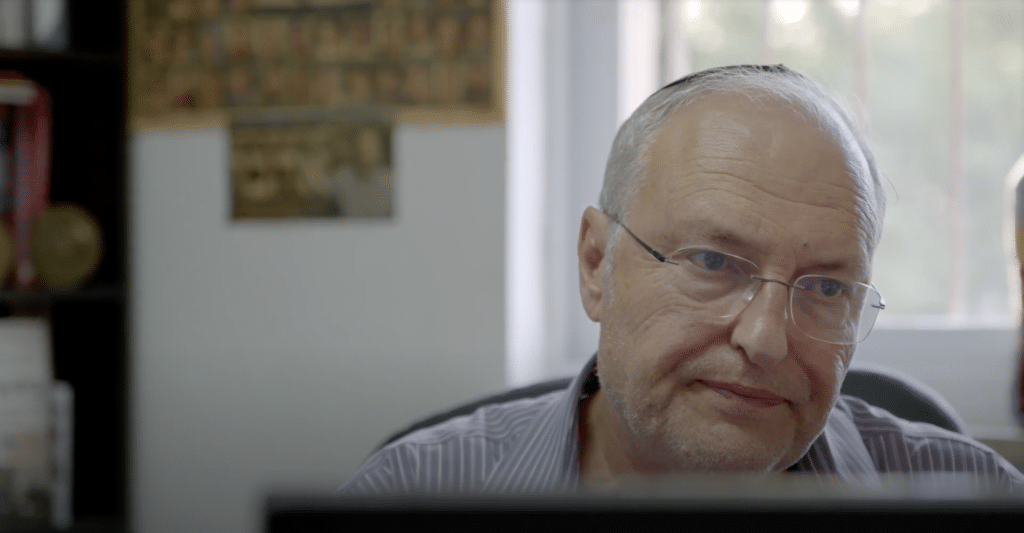

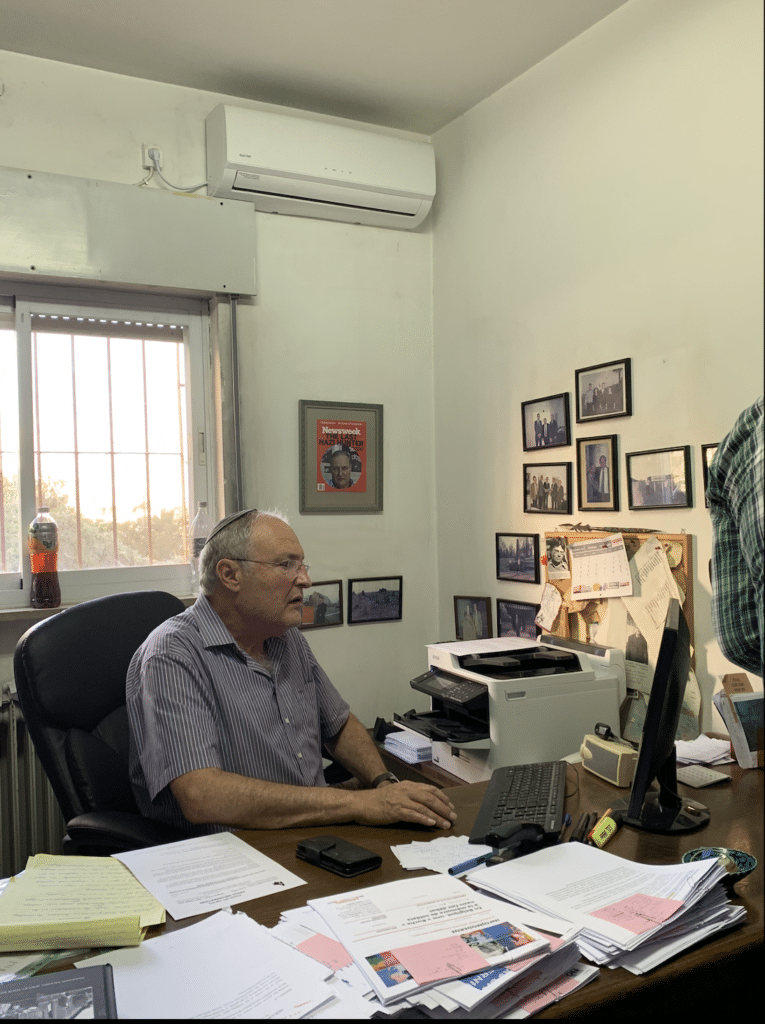

These days, Zuroff works mainly out of his Jerusalem office. Unlike the shiny Hollywood portrayals, his daily work is far less glamorous.

The Simon Wiesenthal Center is a two-bedroom apartment turned office where Zuroff works alongside his assistant. Each room, including the bathroom, is lined top to bottom with case files dating back decades.

By now, those that are complicit in the systematic murder of 11 million Jews and others in the Holocuast are old, frail, and unlikely to be dangerous — but they’re not any less guilty, says Zuroff.

“Unfortunately, there is nothing we can do to bring back a single Jew that was murdered by the Nazis and their helpers,” he told me. “But what we can do is to hold accountable the people responsible for those crimes… We owe it to the victims. And we owe it to their families.”

In fact, he’s tired of answering questions about why we should continue finding and trying Nazis so many years after the fact.

“Let me make one thing crystal clear: in all the cases that I was involved in, I’ve never encountered a Nazi who ever expressed any regret or remorse.”

His work has nothing to do with revenge and everything to do with justice, he said.

“The passage of time in no way diminishes the guilt of the killers. Just because someone reaches the age of 90 doesn’t turn a killer into a righteous gentile.”

These trials are also central to the fight against Holocaust denial and distortion.

“Denial refers to those who say the Holocaust never happened or was grossly exaggerated. Distortion is those who admit the Holocaust took place but change the narrative to diminish the role of their own people.”

“The narrative of those who distort the Holocaust is: ‘The Nazis came to our country and murdered our Jews. Our role? That was just a few social degenerates. They’re not part of our society.’”

Lithuania is one of the main offenders of Holocaust distortion, Zuroff says, also listing Poland, Latvia, Estonia, Ukraine, Croatia, Hungary and Romania.

Uncovering Nazi war criminals from Lithuania, which is where Zuroff’s great-uncle was murdered during the Holocaust, has largely been the focus of his work.

“Lithuania had the highest percentage of Holocaust victims, 220,000 Jews lived in Lithuania and 212,000 were murdered,” he told me. “But not a single Lithuanian sat one day in jail in Lithuania for their crimes.”

Right now, his sights are set on finding a Lithuanian woman who was seen murdering Jewish babies as a teenager during the war. She is estimated to be around 97-years-old.

Unfortunately, the Covid-19 pandemic stalled certain Nazi-hunting efforts, including some leads on that case, but there’s no more time to waste. Death has allowed too many Nazi war criminals to escape justice.

In September of this year, Helmut Oberlander, who was a member of a Nazi death squad, died in Canada without ever standing trial.

“It’s a total travesty of justice,” Zuroff exclaimed.

Cases like Oberlander’s, that ended in death before justice was served, he said, are the most disappointing part of his profession.

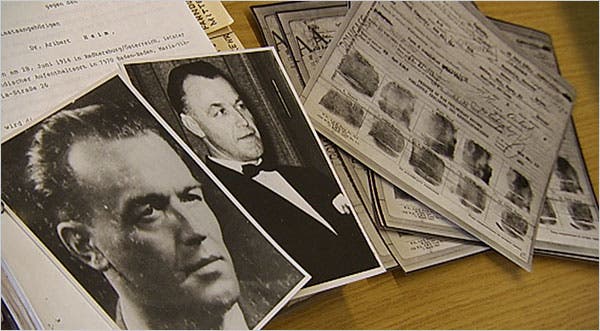

“My biggest regret is not finding Dr. Aribert Heim, Dr. Death of Mauthausen, before he apparently died in Cairo in 1992.”

Heim was nicknamed “Dr. Death” for killing hundreds of inmates at Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria with toxic injections to the heart.

These cases are a constant reminder that Zuroff is racing against the clock and he doesn’t plan to draw the line in the sand anytime soon.

“It sends a message that if you commit crimes like this even many years later, there’s a chance that you may be held accountable.”

One of the things he hopes young people today take away from his work is that seemingly normal people are capable of unspeakable horrors, but that doesn’t exempt them from the consequences.

“Most of the people I was involved in bringing to justice were normative people,” he explained.

“They weren’t involved in crime before the Shoah. They weren’t involved in crime after the Shoah. But during that period of the Third Reich the geopolitical conditions that Nazi Germany created made it more normal to kill a Jew rather than save a Jew.”

One of the greatest tragedies, he explains, is that “people who, under normal circumstances would never have been involved in genocide and homicide, all of a sudden became murderers.”

@jewishunpacked On the 83rd anniversary of Kristallnacht, we spoke to the last hunter tracking down WWII war criminals and bringing them to justice

♬ UNDERWATER WONDERSCAPES (MASTER) – Frederic Bernard

Still, however, they must be brought to justice for their crimes.

“People are judged by what they do, not what they think,” Zuroff reinforces.

This reality has been hard for the families of some Holocaust perpetrators to accept, he adds, because most went on to live outwardly normal lives. He uses the case of Charles Zentai as an example.

Zentai was accused of murdering Péter Balázs, an 18-year-old Jewish man in 1944. According to witnesses, Balázs was not wearing his yellow star on a train, a crime punishable by death in German-occupied Hungary at the time. Zentai allegedly took him to an army barracks, beat him to death and threw his body into the Danube.

Zentai was tracked down and exposed by Zuroff. He was found living in Perth, Australia, after the war.

In the years after Zuroff’s initial investigation, he was visiting Australia on a lecture tour and the children of Charles Zentai approached him for a meeting.

“It’s not every day that one meets the children of a man I had exposed as a Holocaust perpetrator,” he said.

Struggling to reconcile what their father had been accused of, they insisted that “he was a good dad,” Zuroff recalled.

“What you don’t understand, I said to them, is that the overwhelming majority of the people who committed these crimes were absolutely normative people, but under the conditions created by Nazi Germany, perfectly normal people did perfectly abnormal things and committed the most horrendous crimes.”

“That’s why your father [still] has to stand trial,” he told them.

It’s the principle of accountability that Zuroff has dedicated his 40 year career to reinforcing.

He believes it can serve as a warning.

“People who consider committing crimes ask themselves: what are the chances of me getting caught? And what will happen to me if I am caught?”

If you look at the history of the Shoah, he explained, “you could draw the wrong conclusion, because the percentage of people held responsible is not high.”

“These trials are a reminder that justice can also come late and late justice is better than no justice at all.”

Originally Published Nov 10, 2021 12:02AM EST