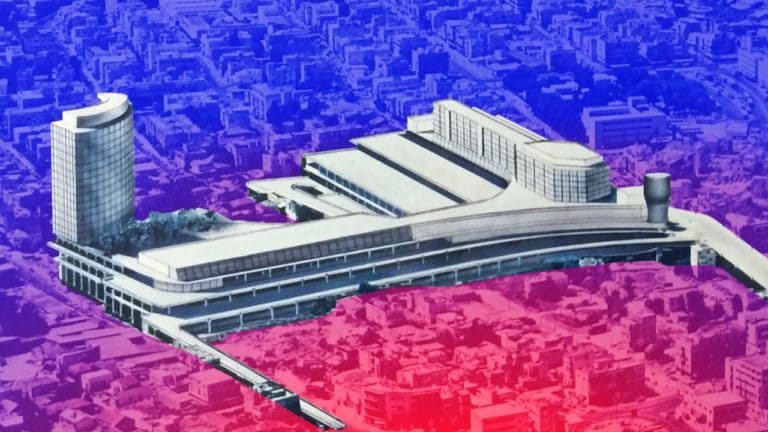

Why did Tel Aviv, a city of just under half a million, build the largest bus station in the world? The “New” Tel Aviv Central Bus Station comprises eight floors and 2.5 million square feet, or about 43 American football fields. That makes the station bigger than New York’s Grand Central, London’s Waterloo, or Shanghai’s General Long Distance Bus Station.

So why did Tel Aviv build this behemoth of a station, one of the most bizarre downright perplexing places on the planet?

The “New” Tel Aviv Central Bus Station is a maze that’s easy to get lost in.

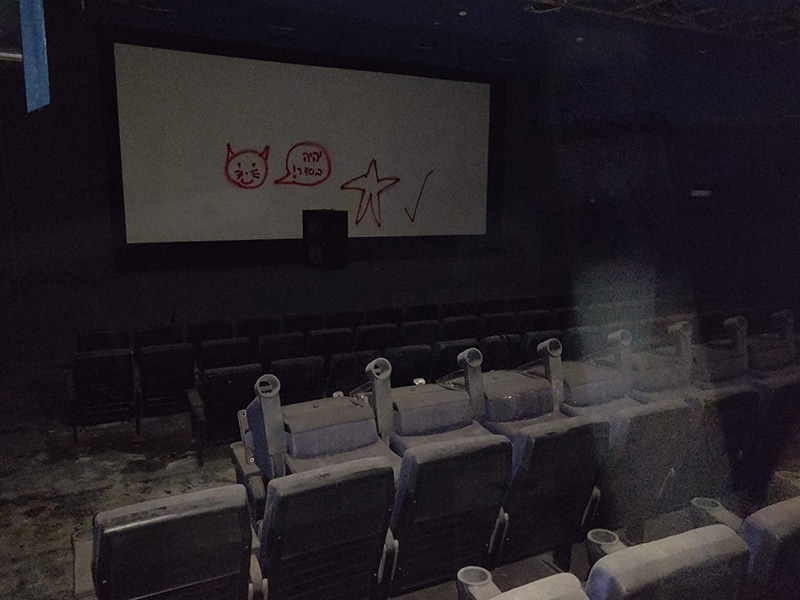

Currently, between its eight floors, three are completely deserted, four and a half are in use, and of those, only three are actually used as bus terminals. There’s an abandoned movie theater and a gigantic nuclear fallout shelter.

Not to mention a free health clinic, a kindergarten, an Asian food market, multiple art galleries, independent theater companies, two synagogues, and even a church – the mosque shut down a few years ago due to lack of demand.

The station’s store owners and frequent visitors include a disproportionate number of refugees, migrant workers, and economically disenfranchised Israelis.

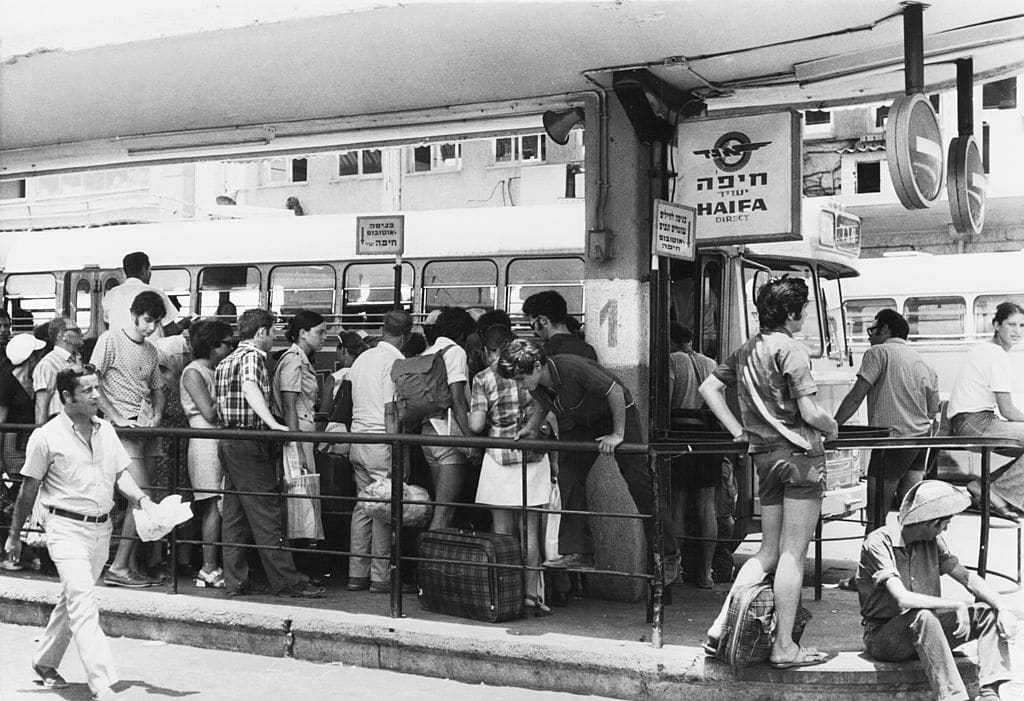

It’s called the “New” Tel Aviv Central Bus Station because it replaced an older one just a few blocks away.

By the 1960s, the old central station was considered a dirty, crowded, and noisy place. Local media called it “the biggest and worst nuisance in Tel Aviv” and “a bone stuck in the city’s throat.” And restaurants nearby complained that their dishes had a smoggy aftertaste.

Aryeh Pilz, a prominent Tel Aviv real estate developer, envisioned the polar opposite of that. He owned land nearby and wanted to build the biggest, most technologically advanced bus station imaginable.

The original plan was a single-story station. But as Pilz kept dreaming bigger and bigger, his ambitious young architect, Ram Karmi, kept revising the original design, and the project ballooned in size, scope, and budget.

To fill all the space, they planned a maze-like design that would encourage passengers to pass by the hundreds of businesses, shops, and entertainment options. To Pilz and Karmi, it was innovation, big business, the future of Tel Aviv –– a “city under one roof.”

Karmi went on to become one of Israel’s most decorated architects. Here’s what Betty from the YouTube channel ARTiculations had to say about Karmi:

Karmi was one of Israel’s most prominent architects. His father was Dov Karmi, one of Israel’s architectural founding fathers, who also won the Israel Prize for Architecture. Ram Karmi graduated from the Architectural Association in London in 1956, and is credited as the architect who introduced the design style “Brutalism” to Israel. The Tel Aviv Central Bus station is a huge example of that. It was his way of “rebelling” against the architectural movement “The Bauhaus International Style” that prevailed in Israel, more specifically Tel Aviv, until the 1950s and 60s.

Karmi claimed to have modeled his design of the Bus Station after “ancient” cities while also incorporating influences from contemporary Brutalist megastructures in Britain, Germany, Japan and North America. The project evolved into a megastructure for many reasons – ever changing architectural programs, not able to raise capital funds throughout the project, convoluted spatial arrangements, scale and magnitude of the building at its final stage, and the complex socio-economic nature of the neighborhood.

To help cover mounting costs, Pilz and his company started aggressively marketing commercial space in the station to lure investors. After Israel’s victory in the 1967 Six-Day War – which we cover in other videos, check them out by clicking the card or the link in the description – he hosted delegations of Jews from overseas to see the skeleton of the structure taking shape in southern Tel Aviv. Many of them saw a goldmine. They hoped shops inside would become valuable real estate assets in the future––wealth they could pass on to future generations.

But growing debt, supply shortages, and a terrible recession slowed construction to a halt. All those early investors, many of whom had spent their life savings, couldn’t open their businesses in a half-finished, non-functioning bus station. For nearly 20 years, the station’s shell sat abandoned. The skeleton of a station came to be known as the city’s “white elephant.”

Squatters settled in and underground rock bands put on concerts in the empty structure. Unlikely residents took refuge in the dark recesses of the station too – when a tunnel was sealed off for construction in the 1980s, a colony of Egyptian fruit bats made it their home.

Finally, in 1993, to much fanfare, the “New” Tel Aviv Central Bus Station opened. 7,000 people, and many prominent officials attended the opening ceremony, including Yitzchak Rabin, the Prime Minister. Onlookers enjoyed free ice cream and officials released a white elephant balloon into the sky to signal the end of an era.

But what opened in 1993 wasn’t exactly the advanced shopping hub of the future Pilz had in mind. His original plan was a 1960s vision for a 1960s world. This was the nineties.

The station’s original planners predicted it would attract about one million passengers and shoppers daily, enough foot traffic to sustain the 1,500 stores inside. It never got close. Today only about 50,000 pass through daily, only 5% of the initial estimate. Traveling by bus is still common practice in Israel, but in 1967 there were only 24,000 private vehicles in Israel. By 1993, it was over a million. Today it’s over 2.5 million.

The big, blocky structure is widely considered to be Tel Aviv’s largest, most disruptive eye sore. It’s also not centrally located for most Tel Aviv residents and doesn’t make the highlights of the city such as the beach, museums, and restaurants easily accessible to people visiting Tel Aviv.

Today, many original investors who once dreamed of passing wealth to kids and grandkids instead pass on exhausting legal disputes. That’s because many stores on the lower floors never gained proper permitting authority. 40% of the building has never been operational.

Abandoned floors have become a haven for drug addicts and other criminal activity. City planners, residents, and activists have called for the station’s demolition or an extensive remodeling. But this would entail complex negotiation with disgruntled shop owners.

And remember those bus station bats? They actually complicate matters considerably. Any remodel or demolition would require the approval of environmental authorities too.

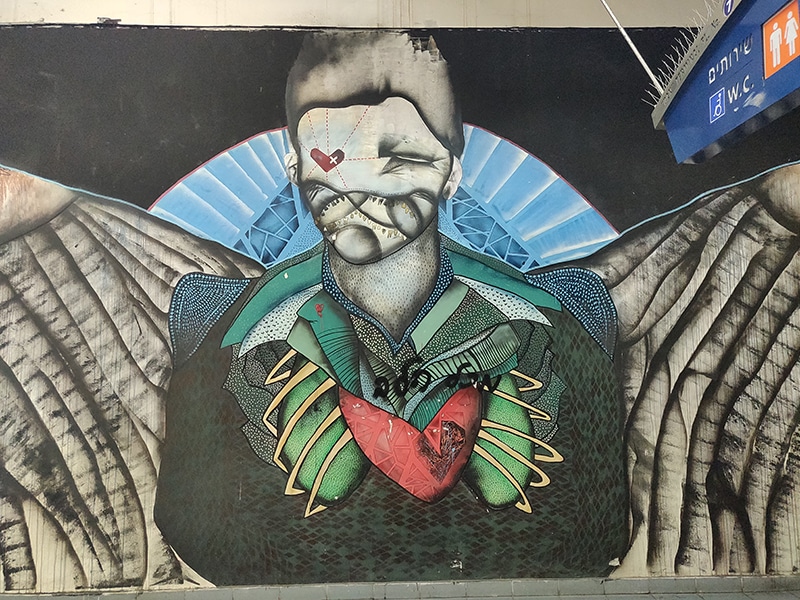

But it’s not all doom and gloom. Cheap rents have made the place a diverse cultural oasis of sorts. The station’s seventh floor is home to a kilometer long graffiti gallery, the largest in Israel. You can find artists renting affordable studio space, Filipino food markets, a Russian New Year-shop each December with Christmas decorations. There’s a Yiddish cultural center and museum with a library containing over 60,000 Yiddish books, a nightclub, legal offices, and a kindergarten. People eke out a living.

A LOT may divide Israelis. BUT, some things actually bring them together. The world’s biggest bus station is one of those things. Here, Israelis of all different backgrounds and circumstances intersect. There aren’t too many other places where Haredis from Bnei Brak, foreign migrant workers from the Philippines and Tel Aviv hipsters all collide.

Sure, maybe the Bus Station is a mess. But according to Mendy Cahan, founder of the Yiddish cultural center inside the station, it’s also a “meshing of creativity” of things that “aren’t mainstream.”

His center sits between a pile of abandoned kiddie rides and a Cyr wheel performer.

Adaptability and perseverance are core tenets of Israeli society––and they’re on display here. On any given day, bus passengers, business owners, foreign workers, artists, museum owners, and others make the best of an imperfect, and strange situation. Together, they keep this broken-down city under a roof functioning.

But of course, it’s not the modern, gleaming city under a roof that was intended. Israel’s history is full of big ambitious plans. Pioneering drip irrigation. Creating the startup nation. Brokering monumental peace deals. Those are some plans that seem to have worked out. But the thing about attempting to carry out many big ambitious plans is, inevitably, some won’t work out.

And that’s how a city with just half a million people ended up with a bloated behemoth of a bus station that feels out of place, and many Israelis hope will eventually be replaced.

Now that you’ve learned a bit about a crazy Brutalist megastructure that took decades to build in Tel Aviv. Are you interested in learning about some other architectural styles in Tel Aviv? What about this “Bauhaus International Style” Ram Karmi was rebelling against? What was that about? Come on over to my channel ARTiculations – where I’ve just made a video about the International Style in Tel Aviv – to learn more about that aspect of the city’s history!

Betty, articulations

However, Tel Aviv was expanding so quickly due to the endless streams of new Jewish immigrants to the city, arguably very few things went according to plan as the city rapidly expanded.

Israel in general was in a state of rapid growth and many grand projects fell a little short. Here’s the YouTube channel Unpacked with a bit more on this:

The greatest example of this was the New Tel Aviv Central Bus Station, dubbed the White Elephant of Tel Aviv – a giant structure abandoned for years. It’s a microcosm for Israel and specifically Tel Aviv’s rapid development in general.

Originally planned in the 1960s, it is the largest bus station in the world, which was crazy for a city that had only 390,000. The way in which this building’s particular construction and size got out of hand is a story that spans decades and weaves through a series of strong personalities, strong dreams, and plans for a modern metropolis. And while its story is one that is still firmly part of the Israeli psyche, it’s not the only dream that never became reality.

While Bauhuas is probably one of the styles Tel Aviv is most recognized for internationally, Brutalism had a stronghold on 1960’s Israeli architecture. One of the most iconic, and perplexing, buildings of the Israeli 1960’s Brutalist style is the “New” Tel Aviv Central Bus Station.

Originally Published Jul 7, 2021 12:03AM EDT