Schwab: Welcome to Jewish History Unpacked where we do exactly what it sounds like, unpack awesome stories in Jewish history.

Yael: I’m Yael Steiner and my childhood dream was to stay in school forever.

Schwab: And I’m Jonathan Schwab and I am in school forever. This week, Yael, it’s your turn to tell me something. So what do you have for us today?

Yael: Before we get into the actual story, I’m going to ask you to imagine something. Imagine if Van Gogh, who I’m assuming you know who he is.

Schwab: I’ve heard of him, yeah.

Yael: Okay. Imagine if Van Gogh, in the middle of his life, each week had decided to paint something that reflected the week’s current events. But it wasn’t just an actual literal depiction of the week’s current events, it was an artistic interpretation of how those events made him feel or how they impacted his community.

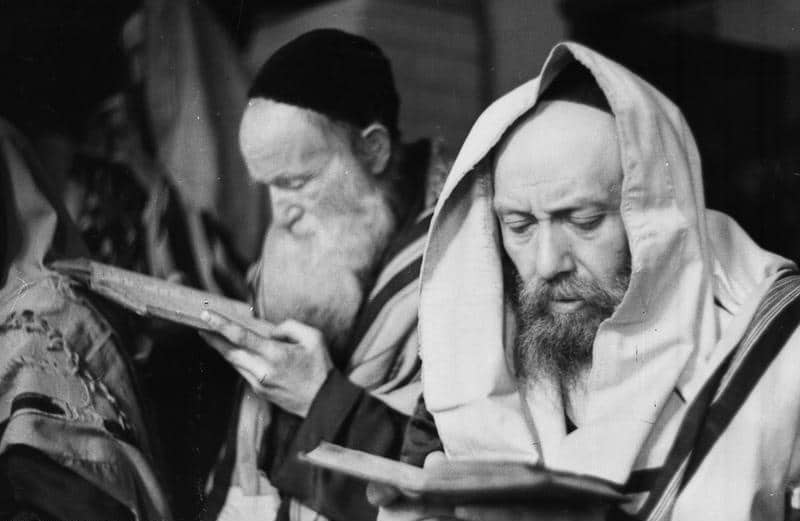

Today, we’re going to talk about an individual, Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapira who did very much the same as I just, uh, proposed Van Gogh might have done. Each week in the Warsaw Ghetto, he prepared a sermon on the weekly Torah portion and his sermons spoke directly to what life was like, without actually telling us what life was like.

He didn’t say, “This week in the ghetto, there was a deportation, or, this week in the ghetto, we didn’t have enough bread.” But he would pull stories from the weekly portion, whether about Abraham, or Moses, and the way in which he would tell them gives us a glimpse into exactly what was happening in the ghetto that week.

Schwab: And do we have other sources also, keeping track, there was a deportation, things like that.

Yael: Thank God, we have a tremendous historical record of what went on in the Warsaw Ghetto from both subsequent testimonies of people who lived there, and also because of the work of Emmanuel Ringelblum, who was a young historian who realized in the midst of the terrible tragedies that were unfolding in Warsaw that one day people are going to need to know about this. And took it upon himself to create a historical archive. The historical archive was called Oneg Shabbos, which literally means in Yiddish, the enjoyment or the glory of shabbos.

And the reason why he called it that was in order to mask what the group’s real goal was, I think he wanted people around him and certainly the Nazis to think that it was just a group of people getting together to enjoy each other’s company on Shabbos, to the extent that that was allowed at the beginning of the ghetto. And what Ringelbum did was appoint a group of collectors, they were known as zamlers in Yiddish, who went around the ghetto and collected not only stories but actual historical documents, pamphlets, newsletters, invitations to weddings, gatherings, underground meetings, Mafia proceedings, and had these zamlers collect and archive this material. And when Ringelbum realized the likelihood that the ghetto would be completely liquidated, he had his group assemble those documents in three different packages and bury them in three different places around the ghetto in the hopes that they would be discovered ultimately after the war.

Schwab: Wow. And the sermons, how did those survive? Or that was part of this archive?

Yael: Ringelbum was a secular historian, but we believe that he was connected to Rabbi Shapira by one of his zamlers, who was a religious Jew. And Rabbi Shapira gave over his manuscripts, not only of the sermons but of other books that he had written, to the Ringelblum archive.

Schwab: There’s so much to talk about. Even just in what you started us off with, of this notion of like awareness that they were living in a historical time and reserving documents for the future. That’s really incredible.

Yael: There are so many different stories that we could unpack here. There’s spiritual resistance of Rabbi Shapira’s determination to bring his followers and his community closer to Torah and closer to faith even under the most dire circumstances. There is the intellectual resistance of Ringelblum and his team in assembling this documentation and the knowledge in the moment that people in the future might not be able to comprehend what is happening here. And then there is really the story of the everyday lives of the people who lived in the ghetto and how they just got through the day.

Schwab: Yeah. Which one are we going down… Or is it all three?

Yael: We’re going to focus today on Rabbi Shapira. And I want to take a few steps back because I, I really have overloaded you with a ton of information.

Schwab: Yeah, yeah.

Yael: Rabbi Shapira was born in 1889 to a Hasidic family. He became the rebbe of a town called Piaseczno when he was a young man and he amassed a rather large group of followers, because of his scholarship, but also because of his temperament and the kind of person that he was.

Schwab: What kind of person was he?

Yael: He was someone who really believed in the intellectual growth of every person and even in the ghetto when there were so many different types of Jews piled on top of each other and people could be suspicious of one another, he was the type of person that spoke to every type of Jew from Hasidic to agnostic. One of the first books that he wrote was something called Chovot HaTalmidim which is, the obligations of the student. And while that sounds very much like a mandate, what it really is, is a treatise on opening your mind. And being curious about the world.

Schwab: I’m guessing that unfortunately where the story goes is that he doesn’t survive the ghetto or the Holocaust.

Yae: He does not nor does Ringelblum. Nor do a majority of the zamlers who were part of the Oneg Shabbos’ archive. The reason why we actually even know that this archive exists is that there were a handful, really no more than a few people, involved in Oneg Shabbos, who did survive the war. And those people remembered the location of one cache of documents. So-

Schwab: Oh, so it’s not like we just happened upon, like we, we wouldn’t even know where these things were.

Yael: Not only wouldn’t we know, we actually don’t know.

Schwab: Where the other ones are?

Yael: Yeah. Ringelblum insisted that the documents be buried in three different locations. And in order not to have his endeavor discovered by the Nazis, he had really kept the members of his group apart from one another.

Like many of the zamlers did not know who the other zamlers were because that limited the chance that the Nazis would discover them and what they were trying to do. So of the handful of people that survived one or maybe a few of them recalled where one cache of documents had been hidden. And in 1946, that cache of documents was unearthed. Unfortunately the type of box that those documents had been hidden in was not watertight.

Schwab: Oh, no.

Yael: And those documents were found to have little or no utility. They were illegible and we don’t know what was in there, which is a tremendous, tremendous shame.

There were however two other caches of documents. No one who survived knew or remembered where they were. One cache has not been discovered to this day. It is possible that at some time in the future someone in Warsaw will uncover a treasure trove of Jewish historical documents that could illuminate so much for us. There is so much potential there. I really do hope that one day that does happen and that those documents are intact. The second cache, which is where the writings of Rabbi Shapira were found among many other thousands of documents, thank God that did survive, was discovered in 1950 by a Polish construction worker who was clearing out-

Schwab: By accident.

Yael: By accident. Clearing out the rubble of the ghetto.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: These documents, the ones that survived, actually survived because they were kept in tin milk containers. So I don’t know when this worker discovered these milk tins. He easily could have disposed of them.

Schwab: Yeah. It sounds so similar to the story of the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls which I think were discovered around the same time. Like really important documents that were discovered by accident by someone who just sort of came across them and then had some inkling that it might be important.

Yael: And that is so very much my hope for the third cache of documents.

Schwab: Yeah, wow.

Yael: Um, the manuscripts that Rabbi Shapira provided were taken by Rabbi Huberband to the Oneg Shabbos people. And ultimately included, luckily in this second cache. We call it the second cache because it was the second one we found. And now have really been studied by so many scholars and have brought so much illumination to what life in the ghetto was like, particularly spiritual life.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Was he recognized as really important at the time or is his importance that we have his work?

Yael: So a little bit of both. He was quite revered as a Hasidic rebbe, as the Piaseczno rebbe. And he had written, as I mentioned, this book, Chovot HaTalmidim and some other manuscripts. And he also took the time in the ghetto while he was writing these sermons to edit and improve upon previous manuscripts that he has written that were also included in the archive that we also have.

Schwab: Did he disseminate those at the time, or like, the first people to read them were the people who discovered them?

Yael: That’s a really good question. I know certain of his writings, Chovos HaTalmidim among them, were disseminated publicly prior to the war or maybe during the war. But I don’t know about the other manuscripts that he edited at that time. And it’s also clear that the sermons that he wrote each week, he intended to be included in one manuscript. Because it wasn’t simply that we found notes jotted down of the sermons that he gave each week, but he did himself collect them into a book that we now know as the Aish Kodesh which means holy fire. And is now a name that people use to refer to Rabbi Shapira. They call him the Aish Kodesh which was never a name he gave himself. Nor was it a name that he ascribed to the writings. He called the writings once collated Torah from the Years of Wrath. Which is a very evocative title.

Schwab: Yeah. I, I got goosebumps hearing that name, but yeah.

Yael: And speaks very much to his feelings about what was going on in the ghetto. Wrath is such an interesting word and leads us into one of the more philosophical elements of Rabbi Shapira’s writings. Wrath indicates to me the imposition of some kind of punishment-

Schwab: It sounds like that’s God’s Wrath.

Yael: Right. It’s not the years of tragedy. It’s not the years of sadness or the years of destruction, or persecution, but it’s wrath, which, I agree with you, sounds like it could only come from God. That title and what Rabbi Shapira had to say about each weekly Torah portion, is what leads many to deem him the father or the arbiter of theodicy.

Theodicy for anyone who doesn’t know, because I certainly didn’t know until I was an adult, is the justification of God’s existence despite evil. Or more simply put, how do we acknowledge a God that lets terrible things happen to us? Or why do bad things happen to good people?

Schwab: Yeah. I’ve heard people use that last one, theodicy, why do bad things happen to good people, if there is a God.

Yael: The first time I ever heard the word theodicy was in the context of a class that was being offered and I thought the class was just about the Odyssey… like Homer’s book.

Schwab: I had the same exact experience (laughs) and I had heard the term many times before I saw it actually written out and it’s not spelled the same way as Odyssey, at all.

Yael: No.

Schwab: And the first time I saw it in print I didn’t know what, what word it was, even though I’ve heard the term.

Yael: I was really scared to ask anyone what it meant for a very long time. But Rabbi Shapira is heavily associated with this concept of theodicy. And that association really grows out of the content of the sermons that he prepared in the ghetto.

I want to take a step back and just talk practically about how these sermons were delivered. In 1939 when certain Jews were ghettoized in Warsaw, Rabbi Shapira began hosting Sabbath services in the small apartment that he had in the ghetto which-

Schwab: And he wasn’t from Warsaw, like he was moved from-

Yael: It’s a great question. I’m not sure at what point he had relocated from Piaseczno to Warsaw. That is…Um, that’s a good question. I don’t know the answer. He held Sabbath services in his apartment ; some weeks up to 300 people gathered around his table to hear from him, which is really quite astounding.

Schwab: Wow.

Yael: And doesn’t mesh with my vision of the ghetto at all. But even under the most trying of circumstances, even when activity, movement worship was limited in the ghetto, he continued to host these services every week.

Schwab: And was sort of like grappling with these questions and these issues in real time.

Yael: Absolutely.

Schwab: People writing, you know, how can God have let the Holocaust happen 10 or 20 years later with a fuller understanding of, of what it was, but like while it was going on. And we have the record of that happening. Okay, yeah, go on. Sorry.

Yael: No, one of the starkest examples of this comes in 1939. There is a German bombing blitz, so to speak, of Warsaw, that results in Rabbi Shapira’s son and daughter-in-law being killed in the fall of ’39.

And after his son’s death there is a six-week period where we do not have a record of a sermon being delivered, which means either he did not give one or he did not record them. He picks back up with recording these sermons which to our knowledge he wrote down on Saturday nights after the Sabbath ended. He picks up with the Torah portion of Chayei Sarah which is the story of the death of the matriarch, Sarah, immediately after the story of Abraham taking Isaac to be sacrificed at the incident known as the Akedah. So in his work on Chayei Sarah, Rabbi Shapira speaks about the fact that it is possible for God to push someone too far.

Schwab: Wow.

Yael: Which is unusual for him because most of his writings were there to create spiritual fortitude in his congregation and how we’ve been here before, the Jews have struggled before, but God is with us and that whatever tragedy is being inflicted upon us is for a reason. With this one sermon on Chayei Sarah, he indicates that he really truly believes that Sarah’s death was a direct result of her vision of her son about to be sacrificed, that that was too far for her. God had taken her too far astray from what she could tolerate and that was why her death occurred.

Schwab: She died as like a traumatic response to tragedy, and he’s writing about this few weeks after the death of his son.

Yael: Yes. And that’s just one sermon that we can tie to what was going on in his life or in the ghetto at that time.

Schwab: Does he reference that directly or this is all-

Yael: No.

Schwab: … sort of oblique? Wow. So we just, we know from other sources that his son died. We see him talking about this but he’s not saying, “And here I am grappling with this because my son was just killed six weeks ago.”

Yael: That’s one of the amazing things about his writings. If you discovered them in a vacuum it is very possible to read them without the knowledge that they were written in the Warsaw Ghetto, that they were written under Nazi occupation. There is no evidence whatsoever that they were written in Poland. He doesn’t reference what is going on around him. But if you study each week’s sermon side by side with the historical record of what was going on in the ghetto at that time, you really can see the parallels. Particularly in 1941, there’s very much a change in Rabbi Shapira’s tone.

I mentioned the sermon that he gave on Chayei Sarah, which was dire, but that was really an outlier for his sermons in the years ’39 and ’40. Before ’41, he often indicated that the suffering that the Jews were going through was part of a normal course of history and maybe part of what was going to garner reward for us in the world to come. Or chevlei mashiach, which we referenced in an earlier podcast, the birth pangs of the Messiah, that this was the tragedy that we needed to go through in order to get to that moment in history when we would be redeemed.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Yeah. I have a very strong visual image in my mind of people crowding into this apartment in an incredibly difficult time and feeling a sense of empowerment, encouragement, support.

Yael: It’s emotional support.

Schwab: Yeah. Like everything seems so awful but here’s somebody who’s making sense of it and perhaps showing like a positive to it. But it sounds like then at some point that’s not the message anymore.

Yael: In 1941, an individual, Grodnitzky, I believe it’s pronounced. It might be Grodnitzky escapes from the Chelmno death camp and makes his way to the Warsaw Ghetto. He reports to the people living in the ghetto what is really going on outside the walls. Not that their persecution within the ghetto was nothing. But that-

Schwab: It gets even worse.

Yael: It gets worse and a tremendous system of extermination of the Jews was being put into place outside the walls of the ghetto and that that’s what they had to look forward to.

Yael: And after the time of this report which, again, the Aish Kodesh himself does not reference. But if you take the dates and line them up.

Schwab: Right. We know when that happened and we know, because that shook the Warsaw Ghetto like just-

Yael: Correct. And that shook him and you see that change in tone in his weekly sermons where he goes from this is something we just have to get through to get to a better place, whether it’s in this world or the world to come, and he switches over to this notion that this is something that needs to happen. We don’t know why. And God himself is having a hard time watching us suffer this way and he has closed himself off to the Jews in a chamber. Because if He were to watch us suffering, He would act and that action would destroy the world. It’s very kabbalistic, and complicated, but it speaks to someone who could not face the possibility that there was a God who would willingly do terrible things to the people of the world, particularly the Jewish people. And that’s really what Rabbi Shapira is known for.

Schwab: Yeah. it’s interesting because it reminds me of what you were saying earlier about his sermon on Chayei Sarah and the idea of like a tragedy that is so awful, a person can’t bear it anymore and it sounds like he’s been applying the same thing. Like this tragedy is so awful God can’t bear it and he, he’s like personalizing God in that way and, and therefore God is, is like less present, maybe, right? Am I understanding the idea correctly?

Yael: Yeah, I think so. I think he’s saying that God isn’t turning his back on us, but he’s sort of hiding from us right now. And we don’t know why. And he didn’t need to know why to have faith, which, I don’t think that most people could live that way. But I think he knew that the people in the ghetto needed something to cling on to and that really, is very much in line with his pedagogy which we know about from the Yeshiva that he started in the 1920s where he really addressed each student as that student needed to be addressed. He was much less stern than other heads of Yeshivot at that time and he really believed in the inner expression of each student.

He reminds me of another figure from the Warsaw Ghetto, Dr. Janusz Korczak. He was a pediatrician and the head of an orphanage in Warsaw and he lived among his orphans and eventually despite being offered a chance to escape, accompanied them to their deaths, walked with them with his head held high with the children dressed cleanly and neatly to, the Umschlagplatz in Warsaw which was the railroad junction where the cattle cars were loaded and I kept seeing him pop into my head when I read about Rabbi Shapira, because he really created, an atmosphere for the children he was leading that gave them emotional strength. He had the children read and write and perform plays and he tried to keep a sense of normalcy for them as long as possible. Rabbi Shapira also, due to him being a well-known individual, was treated slightly better not by the Nazis, but by the inner workings of the ghetto. Um, he was offered a position in a workshop. many of the other people who worked in the workshop were also well-known rabbis and there is testimony that the discussion in the workshop while people were recycling used clothing into fabric for the Nazis was just top level Torah discussion.

And ultimately when the ghetto was liquidated, Rabbi Shapira went to a work camp. He was offered a chance to escape from the work camp, but he, like Dr. Korczak, basically said, “If my Hasidim are not going to be rescued, I’m not going to be rescued.” And he was ultimately shot with the entire population of the work camp, after uprisings had occurred in Warsaw. And the death camp at Sobibor and some other places. That might not all be in super chronological order but there’s a lot of wonderful historical writing that’s been done about both Oneg Shabbos and the Aish Kodesh. Our educational lead on this podcast, Dr. Henry Abramson, has an amazing book on the topic, On the Torah from the Days of Wrath that I really recommend. He was really instrumental, in helping me prepare this podcast and he also explained a little bit of the historiography to me which is that after this cache was discovered in 1950, there was an individual in Israel named Baruch Duvdevani who returned to Warsaw, retrieved the materials from the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw where it was kind of languishing. And published the Aish Kodesh for the first time.

Schwab: Wow.

Yael: And it was only discovered many years later that the first publication of the Aish Kodesh was not 100% consistent with the original manuscript. Because if you look at the handwritten pages from Rabbi Shapira, you see numerous, numerous changes, cross-outs and footnotes, and copy edits. And if you read Dr. Abramson’s book, you will see a lot of fascinating material that emanates from these copy edits. You can see how Rabbi Shapira’s mind changed about certain things over the course of the war.

Schwab: Wow, god.

Yael: Um, so ultimately several historians both before Dr. Abramson, and Dr. Abramson himself have written about the manuscript and the different changes, two, there are two changes that I want to talk about as we wrap up because I think they really encapsulate the struggle that Rabbi Shapira and the Jews of the ghetto took on as they tried to maintain some sense of spirituality and fidelity to religion under really trying circumstances. One is that on the cover of a manuscript not of the Aish Kodesh but of another book that you can see Rabbi Shapira edited during his time in the ghetto and that was included in the archive, under his name there is something crossed out very violently and aggressively.

And a modern historian has used breakthrough technological techniques to reveal what was underneath that cross-out. And what it said was, “av beit din Piaseczno,” which means the head of the Jewish rabbinical court in Piaseczno.

And Dr. Abramson posits that the reason why that was crossed out so violently is that once Rabbi Shapira realized there were no more Jews of Piaseczno, there was no community to preside over as an av beit din, he had to eliminate that title, both from the book, but also from his being.

Schwab: Yeah. Like how often do we see that in a historical document like someone’s actual feelings? Not them writing, “Here’s how I’m feeling. I’m despairing or I’m losing this hope or, or I’m just incredibly horrified and sad about what’s happening,” but like be able to actually really feel the feeling through what they did. Wow.

Yael: The other amendment that I want to talk about is with respect to a sermon that Rabbi Shapira gave on the topic of Hanukkah in 1941, he was still writing as though redemption might be upon us and he spoke about the trials and tribulations that the Jews experienced during persecution, and he also mentioned, “We’ve been here before. The Jews have struggled before. We have been persecuted by this group and that group and we will come out of this the same way.”

This is nothing we haven’t seen in the past. In 1942, after the escapee from Chelmno had told them what was going on outside and after things had really deteriorated in the ghetto, Rabbi Shapira went back and amended his sermon from that time and said, “I was wrong. We have never experienced persecution like this before.”

Schwab: Yeah, yeah. I feel like that anecdote sums up the entire thing for me of, I thought at the beginning this is a story of just like realizing one’s place in history or, or how do we use historical context to like better understand what someone is writing. But it’s really a story of this like, of the struggle of faith. How does our faith change with us when we encounter the impossible, I guess, for lack of a better term.

Yael: And I think Rabbi Shapira was realizing that this is a completely unique situation, hopefully one never to be repeated. It reminds me of something I discussed with Dr. Abramson, which is that this document, the Aish Kodesh, is so generous. It’s one of a kind. There is absolutely nothing like it in our history, where we have a first-hand contemporaneous account of what is going on and how Jews are being treated, but written in a way that requires interpretation. It’s a marvelous piece of writing.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: and He tried at the very beginning, I think, to reinforce for his community that Jews have suffered in the past and will suffer in the future. But in the midst of it all, he realized he was in a unique time in Jewish history.

Schwab: I know we’re close to the end here and I almost want to say like, how do we end on like a positive or optimistic, or even like any sort of different note. But, but that’s sort of the story of this whole document is, it doesn’t end. Like he doesn’t get a chance then to years later give a closing to this in any way, right? Because he doesn’t survive. We only get to see what he was grappling with at the time and then it’s it, then it’s over.

Yael: For me, there are two takeaways here. One is a tremendous amount of gratitude to him and to Emmanuel Ringelbum and to all the people who had the foresight to put together this historical archive because they knew that future generations would need to see it. Whether or not they believed there would be future generations of Jews that the future of the world needed to see it.

Um, and then also that we are still here and we are still talking about it and we are able to benefit from both the scholarly Torah work of Rabbi Shapira and also the philosophical challenges that he raises. There is a scholarly debate as to whether or not Rabbi Shapira did lose his faith or not before the end. We certainly don’t have time to get into that now but it’s definitely something to think about and I just have gratitude to the people who sacrificed, uh, themselves to make sure that we know what they went through.

Schwab: Yeah, wow. Yeah.

Yael: On that note, thanks for, uh, taking the time to listen.

Schwab: Yeah. Thank you for sharing. I feel like this story is different than a lot of the other ones that we’ve talked about, but it’s a very moving one.

Yael: Yes. Tremendously impactful and I really do recommend that any of you who are touched by this story, read more about the Piaseczno Rebbe, read more about the Oneg Shabbos archive. It really contains multitudes not only religious documents, but you know things that really illuminate for us what life was like in the ghetto, and was put together at great risk to those who collected those items. And I think we owe it to them to, to learn.