Israelis are heading to the polls for the country’s fifth election within four years, on November 1. If you want an insider’s guide to this year’s elections, it’s all right here for you — the latest polls, campaign ads, the top issues, and more.

Campaign ads from the 2022 election

If you want to understand the overall political mood of an election, one of the best ways to do it is by watching campaign ads. As is tradition here at Unpacked, we’ve collected campaign ads from parties across the political spectrum with English subtitles.

After watching the ads in the link above, consider who you think is running the best campaign for the next Knesset. Which party do you think has the best messaging? And which party would get your vote?

Who’s winning in the polls?

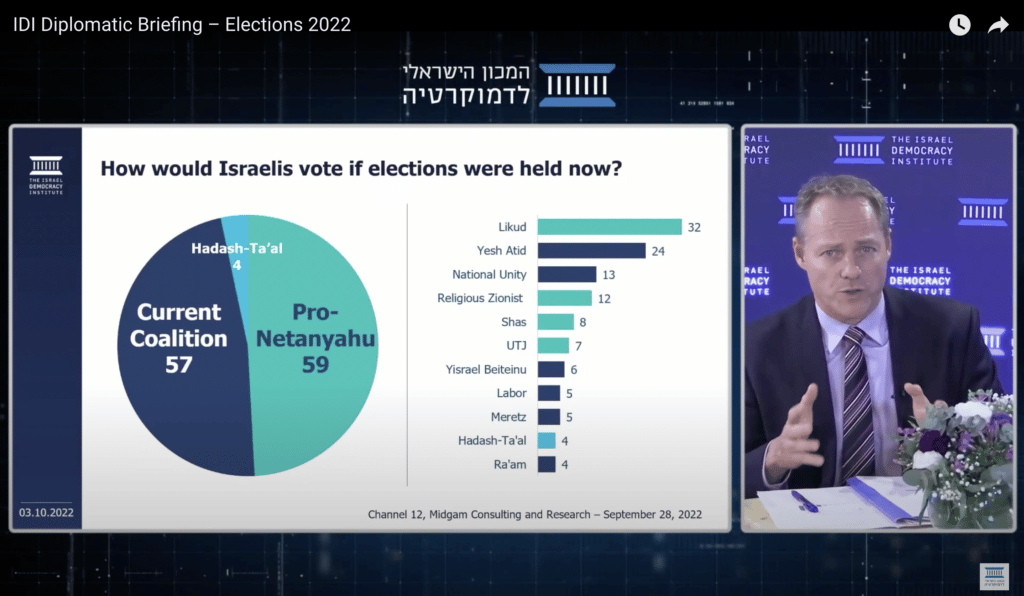

The latest election polls show the Benjamin Netanyahu-led bloc obtaining 59 to 60 seats (just short of a majority).

Meanwhile, the parties in the current coalition would get 56 to 57 seats, and about four seats are predicted to go to the Arab parties Hadash-Ta’al (which have previously resisted joining any coalition).

The polls show Likud obtaining the highest number of seats, followed by Yesh Atid, the National Unity party, and the Religious Zionism-Otzmah Yehudit party.

(Screenshot: Israel Democracy Institute briefing on the 2022 elections)

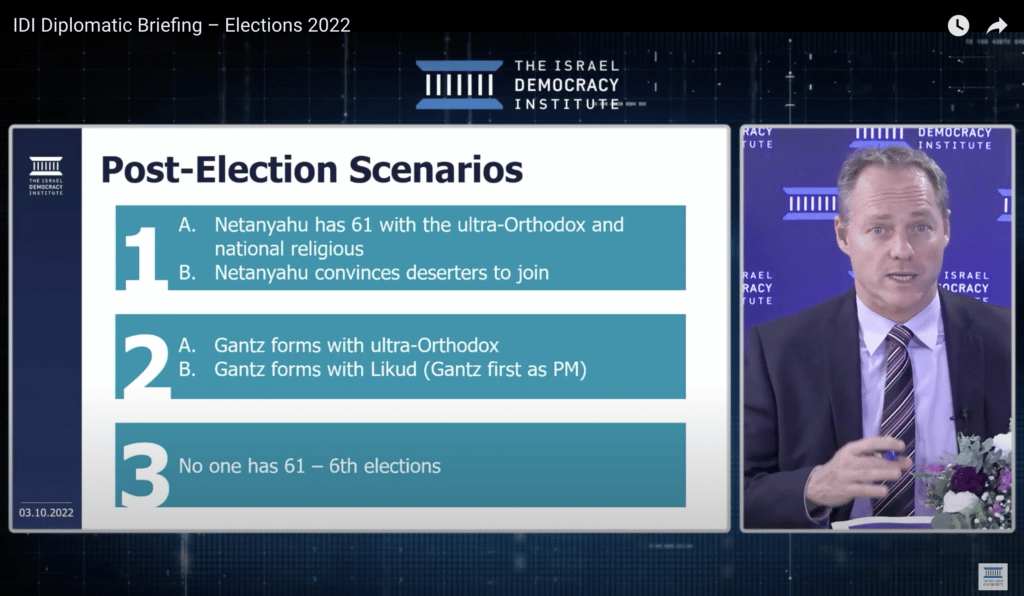

If the election results follow this polling and Likud wins the highest number of seats, then Benjamin Netanyahu, as the Likud leader, would have the first opportunity to form a coalition.

If the pro-Netanyahu parties win fewer than 61 seats, Netanyahu could try to convince another party from Israeli Prime Minister Yair Lapid’s bloc to join his coalition.

One possibility “is a rotation government comprising of Likud headed by Netanyahu, the National Unity party formed by Benny Gantz and Gideon Sa’ar, and the ultra-Orthodox parties,” the Israeli political analyst Samuel Hyde wrote in The Jewish Journal.

Other possible post-election scenarios include one of the blocs winning at least 61 seats, or neither bloc being able to obtain 61 seats (which could trigger the sixth election).

(Screenshot: Israel Democracy Institute briefing on the 2022 elections)

What are the main issues in the election?

According to the Israel Democracy Institute, when asked which factors most influence their vote, Israelis cite the economy, the identity of the party leader, and religion and state as top priorities. But many commentators expressed doubt that this would actually affect voting patterns.

“We are deeply immersed in identity politics — one’s level of religiosity and sense of belonging to a sociological tribe,” Yohanan Plesner, president of the Israel Democracy Institute, explained.

The questions of “which tribe [I belong to] and which political party I voted for in the past” impact Israelis’ voting behavior a lot more than policy issues, he added.

Plus, Plesner continued, there are very few ideological divisions between the parties: “It would be difficult to pinpoint the differences between the parties,” or between Netanyahu and Lapid, on questions of economic policy, for example.

Instead of being about policy, the debate focuses on one individual, Israeli political commentator Samuel Hyde argued. “The fight over ‘Bibi yay or Bibi nay’ has tainted much of the discourse to the point of rendering policy discussions meaningless,” he wrote in The Jewish Journal.

“Where we are at is simple: Netanyahu’s supporters believe that there is no future without him, and his opponents believe that there is no future with him,” he added.

This is evident in the candidates’ rhetoric. For instance, last month, Lapid said in an interview with the Israeli newspaper Makor Rishon that “The worst thing that can happen to Israel is Benjamin Netanyahu being in the political sphere. It is absolutely the worst thing possible.”

Similarly, National Unity party leader Benny Gantz’s campaign slogan says that Netanyahu’s reelection would be “Israel’s November nightmare.”

Netanyahu, on the other hand, is arguing that “Israel is going backward. Our national pride is at a low we couldn’t imagine.” Only he and the Likud party, Netanyahu argues, can return Israel to the proud, stable, and secure country it is meant to be.

Meanwhile, in an op-ed for Arutz Sheva, Benjamin Sipzner, who is campaigning on behalf of the Religious Zionism party, lamented that elections in Israel have become about one individual.

“Israel’s elections should not be centered around one person, they should not be vacant of ideology and content,” he wrote.

“We should think about our vision of Israel, its Jewish identity, its army and security forces, and our heritage. We need to think about the politicians and parties who will help promote that vision.”

One substantive issue on the table, according to David Makovsky of the Washington Institute, is Israel’s democracy.

The members of the anti-Bibi bloc are “united by a fear that democratic norms will erode if Netanyahu’s Likud Party wins,” he wrote in a blog post.

“Likud representatives in the Knesset have openly stated that should Netanyahu return to power, they will fire the current attorney-general, alter the manner in which that post is filled, and pass a law deferring their leader’s corruption trial until after he exits politics,” he explained.

How did we get here? A refresher

Let’s take a step back. Why are Israelis going to the polls again? Here’s a refresher of Israeli politics in the past year leading up to this moment.

In the 2021 elections, the Likud party received the highest number of seats. When Benjamin Netanyahu (as the leader of Likud) failed to form a coalition, Yair Lapid, as the leader of the second largest party, was given the mandate to do so.

Together with Naftali Bennett, Lapid then did what many had thought to be impossible: he succeeded in forming a coalition of eight ideologically-diverse parties, including left-wing, right-wing, centrist and Islamist parties.

In June 2021, the new government was sworn in with Bennett as Prime Minister and Lapid set to become prime minister in August 2023.

The coalition collapsed a year later when the coalition failed to renew a law regulating Israeli settlements in the West Bank. This prompted Yamina MK Nir Orbach to leave the coalition, dropping the ruling bloc to minority status with just 59 seats.

Lapid immediately became Prime Minister (under a stipulation in the coalition agreement that this would happen if the government were brought down prematurely). And it triggered Israel’s fifth elections within four years.

How do Israeli elections and coalitions work again?

Israel’s parliament, called the Knesset, has 120 seats. Each voter casts one vote for a political party (not any specific candidate) to represent them in the Knesset.

Prior to the election, each party submits a list of candidates in rank order for entry into the Knesset. Each party gains a particular number of seats in the Knesset based on the proportion of the vote they receive. Those seats are then filled by the candidates in the order they are ranked.

But there’s a caveat to this. A party must earn at least 3.25% of the vote to be able to enter the Knesset at all — this is known as the electoral threshold.

With 120 total Knesset seats, a majority of 61 seats are needed to form a government. No single party has ever won an absolute majority in the Knesset — therefore, several parties must join together in a coalition to form the government.

Israel’s president (currently Isaac Herzog) chooses the Knesset member who is most likely to form a coalition. Typically, this person is the leader of the party that received the most votes.

That person then has six weeks to build a coalition with other willing parties. If this coalition is approved by a majority of Knesset members, that person becomes the prime minister and the coalition becomes the government.

Once the coalition is decided, the rest of the Knesset members become the “opposition.” Although Israel’s national elections officially take place every four years, the Knesset can decide to dissolve itself and hold new elections at any time by a simple majority vote.

The last time the Knesset lasted for the full four-year term was more than 30 years ago. The Knesset can also vote to extend the four years under special circumstances: this happened in 1973 when Golda Meir continued serving as prime minister during the Yom Kippur War.

Originally Published Oct 19, 2022 12:02AM EDT